Wiki Article

Superconducting quantum computing

Nguồn dữ liệu từ Wikipedia, hiển thị bởi DefZone.Net

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (October 2025) |

Superconducting quantum computing is a branch of quantum computing and solid state physics that implements superconducting electronic circuits as qubits in a quantum processor. These devices are typically microwave-frequency electronic circuits containing Josephson junctions, which are fabricated on solid state chips.

Superconducting circuits are one of many possible physical implementations of qubits, the quantum computer's equivalent of a traditional bit in a classic computer.[1] Qubits refer to a two-state quantum mechanical system, and have two logic states, the ground state and the excited state, often denoted (for ground and excited), or .[2] Superconducting quantum computing implementations are categorized as "solid state" quantum computers, where qubits are intrinsically integrated in a solid-state device. Solid state quantum computers also borrow fabrication techniques developed for solid state classical computation.[3]

Superconducting architecture is the dominant method in the industry for developing quantum processing units, or QPUs. Research in superconducting quantum computing is conducted by companies such as Google,[4] IBM,[5] IMEC,[6] BBN Technologies,[7] Rigetti,[8] and Intel.[9] Alternatives to superconducting qubits include trapped ions, and neutral atoms.

Ongoing research in superconducting quantum computing includes device-level improvement, developing error correction methods, and demonstrating quantum advantage by comparing a quantum processor's performance to a classical computer.

History

[edit]Quantum computers were first proposed by Richard Feynman, who in 1982 proposed using such a computer to simulate and understand the properties of other quantum systems. In the 1990s, two quantum algorithms were published, which further stirred interest in realizing quantum computers. Peter Shor proposed Shor's alogrithm, a quantum algorithm for finding the prime factors of an integer, which could in theory break RSA encryption. Similarly, Lov Grover proposed the Grover search algorithm, which provides an alternative to binary search that can be done with quadratic speedup.

At the time, superconducting quantum circuits were already being used to construct highly sensitive SQUID devices, and had also been used to demonstrate macroscopic quantum phenomena, such as quantized energy levels. It became apparent that these superconducting qubits could be used to achieve quantum computation.[10] This was especially true because such "solid state" approaches to quantum computing were seen as far more viable than other approaches at the time, including NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) quantum computing, due in part to the fact that existing fabrication techniques would apply.[11]

In 1999, a paper[12] was published by Yasunobu Nakamura, demosntrating the first superconducting qubit. It is a form of Cooper pair box, now known as the "charge qubit". Although the design had been proposed in 1997 by the Saclay team (including Devoret), this paper was the first to show coherent control and readout, in the form of Rabi oscillations between the ground and excited states of the qubit. However, even after this first result, it was unclear if superconducting qubits would be viable, and some argued that the system was not truly capable of containing quantum information.[13] Part of the problem was that this initial design maintained coherence for less than a nanosecond, not long enough to do any calculations.

In the following years, several other superconducting qubits were invented, including the phase qubit, flux qubit, quatronium, the transmon qubit, and the fluxonium. The transmon design, which has reduced sensitivity to charge noise, is now widely and primarily used in superconducting quantum computing.[10] Further developments in readout and design have allowed superconducting transmon qubits to reach millisecond coherence times.[14]

Google in 2016, implemented 16 qubits to convey a demonstration of the Fermi-Hubbard Model. In another experiment, Google used 17 qubits to optimize the Sherrington-Kirkpatrick model. In 2019, Google produced the Sycamore quantum computer which performed a task in 200 seconds that Google claimed would have taken 10,000 years on a classical computer.[15] The task was random circuit sampling, a common benchmark for claims of "quantum supremacy" or quantum advantage.

As of 2025, superconducting quantum processors have exceeded 1,000 qubits, the largest being IBM Condor, a 1,121-qubit quantum processor.[16][17] In 2025, Google announced one of the first independently verifiable quantum advantages on hardware using the Willow processor.[18]

Background

[edit]Quantum computing

[edit]Classical computation models rely on physical implementations consistent with the laws of classical mechanics.[19] Some very small systems, or certain systems under extreme conditions, are instead described by the quantum mechanics, which obey different sets of physcial rules.

Quantum computation is a method of constructing a quantum system for the purpose of encoding information. Applications of a quantum computer would include simulating quantum phenomena beyond the scope of classical approximation, and speeding up certain calculations, particularly those that involve an "oracle". Certain algorithms designed for quantum computers, such as Grover Search or Shor's algorithm, are believed to be able to do some calculations better than their classical counterparts.

Gate-based quantum computing is a method of quantum computing that, much like traditional computing, use qubits (analogous to bits) and quantum gates (analogous to classical gates).

Qubits

[edit]

A qubit is any two-level system in quantum mechanics. Much like a classical bit, it is a system with two possible states. However, the difference lies in the fact that because a qubit obeys the laws of quantum mechanics, it is capable of occupying a quantum superposition of both states.

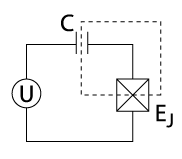

The primary requirement for physically constructing a qubit is the ability to be able to individually address the first two states, in this case energy levels, of the system. This is difficult, as most systems contain a near-infinite number of energy levels. In superconducting quantum computers, these qubits are constructed using superconducting resonant circuits. Each superconducting qubit is essentially a nonlinear LC circuit with a capacitor and a Josephson junction, a superconducting element with a nonlinear inductance.[20] Because the circuit is non-linear, there is unequal spacing between its energy levels, allowing the first two states to be individually addressable.

In theory, due to its nonlinearity, the qubit is affected only by photons with the energy difference required to jump from the ground state to the excited state.[20] In practice, however, noise in the system can still cause it to leave the computational subspace. In many cases, the higher energy levels of a superconducting qubit need to be considered.[21] This is especially true in transmons, which have weak anharmonicity by design.

Because the circuit is superconducting, it has zero resistance, and dissipates almost no energy. However, this comes at the price of extremely low operation temperatures.

Quantum gates

[edit]A quantum gate is a generalization of a logic gate describing the transformation of qubits from their initial state to a different state, often a superposition.

In superconducting qubits, quantum gates are implemented as microscopic pulses applied to the circuit using microwave resonators. Pulses are sent through resonators capacatively coupled to the qubit, which are harmonic oscillators that are detuned from the qubit itself. By applying an external drive to the qubit, the normal unitary evolution of the system implements a single qubit gate after a certain length of time has passed.[23]

Two qubit gates, such as the iSWAP gate, can be achieved through coherent exchange or parametric coupling between two qubits.[23] In coherent exchange, the transition frequency of one of the qubits is tuned such that it matches the transition frequency of the second qubit. This method relies on the frequency tunability of the qubit, and does not work in fixed-frequency cases.[23] Parametric coupling on the other hand is done by changing the coupling constant between two qubits at the sum or difference of their two frequencies.[24]

Criteria for a viable quantum processor

[edit]There are many possible physical implementations of qubits, with superconducting circuits being one of them. In order for a given implementation to be considered viable for constructing a quantum computer, one set of criterion is the DiVincenzo's criteria,[25] a set of criteria for the physical implementation of superconducting quantum computing. The initial five criteria ensure that the quantum computer is in line with the postulates of quantum mechanics and the remaining two pertaining to the relaying of this information over a network.[citation needed]

Superconducting qubits already meet a large number of DiVincenzo's criteria. They are already highly scalable from a fabrication standpoint, they can be initialized by thermal relaxation, and single-qubit gates combined with two-qubit gates form a universal gate set. However, superconducting qubits still struggle with having short coherence times, making preserving quantum information a challenge.

Superconductors

[edit]Superconducting qubits are circuits made from superconducting metal material. Superconductivity is a phenomenon that occurs in some metals at low temperatures where electrical current experiences zero resistance in a material, allowing the current to flow without loss of energy, and be nearly dissipation-less.[26]

This phenomenon occurs because the basic charge carriers are pairs of electrons (known as Cooper pairs), rather than single electrons as found in typical conductors.[27] While single electrons are fermions (with half-integer spin), Cooper pairs of electrons are bosons (with integer spin), and as such they no longer obey the Pauli exclusion principle, meaning these Cooper pairs can occupy the same states. Under certain conditions, this allows them to form a state of matter known as a Bose–Einstein condensate, where all of the pairs of electrons in the condensate each occupy the same position in space and have equal momentum. In this way, there is nothing distinguishing the pairs from each other, and they occupy the same state. As a result, the electron pairs move coherently as a single wave, bypassing the disturbances in the lattice that usually cause resistance. Thus, superconductors possess near infinite conductivity and near zero resistance.

Superconductivity generally only occurs near absolute zero, since that is when it is more energetically favorable for electrons to pair up than repel each other. This is one of the primary reasons why superconducting qubits must be cooled to ultra cold temperatures.

Superconducting electrical circuits

[edit]Superconducting electrical circuits are networks of electrical elements described by a single condensate wave function, wherein charge flow is well-defined by some complex probability amplitude. Quantization in the circuit results from complex amplitude continuity, since only discrete numbers of magnetic flux quanta can penetrate a superconducting loop. Parameters of superconducting circuits are designed by setting (classical) values to the electrical elements composing them, such as capacitance or inductance.[citation needed]

Josephson junctions

[edit]One distinguishing attribute of superconducting quantum circuits is the Josephson junction, an electrical element which does not exist in normal conductors. The junction is a weak connection between two superconductors on either side of a thin layer of insulator material only a few atoms thick. The resulting Josephson junction device exhibits the Josephson effect, whereby the condensate wave function on the two sides of the junction are weakly correlated. Current flows through the junction due to quantum tunneling.

The Josephson junction exhibits a nonlinear inductance, which allows for anharmonic oscillators for which energy levels are discretized (or quantized) with nonuniform spacing between energy levels, denoted .[2] In contrast, the quantum harmonic oscillator cannot be used as a qubit as there is no way to address only two of its states, given that the spacing between every energy level and the next is exactly the same.

For any qubit implementation, the logical quantum states are mapped to different states of the physical system (typically to discrete energy levels or their quantum superpositions). Different superconducting qubit designs have different ranges of Josephson energy to charging energy ratio. Josephson energy refers to the energy stored in Josephson junctions when current passes through, and charging energy is the energy required for one Cooper pair to charge the junction's total capacitance.[28] Josephson energy can be written as

- ,

where is the critical current parameter of the Josephson junction, is (superconducting) flux quantum, and is the phase difference across the junction.[28] Notice that the term indicates nonlinearity of the Josephson junction.[28] Charge energy is written as

- ,

where is the junction's capacitance and is electron charge.[28]

Circuit quantization

[edit]Circuit quantization is a method of obtaining a quantum mechanical description of an electrical circuit. The end result is a Hamiltonian describing the energy of the system, from which other properties such as the ground and excited state can be derived.

In circuit quantization, all electrical elements in the circuit are rewritten in terms of the condensate wave function's amplitude and phase, as opposed to the current and voltage. Then, generalized Kirchhoff's circuit laws are applied at every node of the circuit network to obtain the system's equations of motion. Finally, these equations of motion must be reformulated to Lagrangian mechanics such that a quantum Hamiltonian is derived describing the total energy of the system.[citation needed]

Circuit quantum electrodynamics

[edit]Properties of superconducting electrical circuits coupled to a resonator are described by the framework of circuit quantum electrodynamics, or cQED. Superconducting qubits generally need to be connected to a resonator in order to protect them from environmental noise, and to allow them to be coupled to each other. The cQED framework is similar to cavity QED and uses largely the same techniques. In physical implementations, the resonator is usually an on-chip coplanar waveguide readout resonator, a superconducting LC resonator, or a high purity cavity.

Hardware and technology

[edit]Superconducting quantum computing devices are typically designed in the radio-frequency spectrum, cooled in dilution refrigerators below 15 mK and addressed with conventional electronic instruments, e.g. frequency synthesizers and spectrum analyzers. Typical dimensions fall on the range of micrometers, with sub-micrometer resolution, allowing for the convenient design of a Hamiltonian system with well-established integrated circuit technology.

Manufacturing

[edit]

Manufacturing superconducting qubits follows a process involving lithography, depositing of metal, etching, and controlled oxidation.[29] This process is similar, though not the same, as CMOS (Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor) fabrication used for commercial silicon computer chips.[30] A major difference is the use of electron-beam lithography, as opposed to optical lithographic techniques, which is hard to scale and has low yield.[31] However, electron beams allow for a much sharper resolution, which is often necessary for certain device designs.

The superconductor used to make superconducting circuits is usually aluminum, deposited on a silicon substrate, but can also be niobium or tantalum, both d-band superconductors.[32]

Improvements in fabrication continue to improve the lifetime of superconducting qubits and have made significant improvements since the early 2000s.[29]: 4

Refrigeration

[edit]Cryogenic dilution refrigerators are used to keep the superconducting circuits cold. They are cooled to temperatures below 15 mK. Although superconductivity itself onsets before this temperature, a large population of thermal quasiparticles exist within the circuit, which can interfere with the circuit's superconductivity. These so-called 'equilibrium quasiparticles' are exponentially suppressed at lower temperatures.[33] Therefore, it is favorable to cool the circuit to as low of a temperature as possible.

Inside of the dilution fridge, the superconducting circuits are connected to various filters and amplifiers that enable the qubit to be read out from observers outside of the dilution fridge.

Qubit types

[edit]Phase, flux, and charge qubits

[edit]The three primary superconducting qubit archetypes are the phase, charge and flux qubit. These archetypes correspond to limits of the underlying Josephson hamiltonian. Depending on what limit the hamiltonian is in, a different aspect of the qubit will be well defined. The choice of qubit archetype impacts the qubit's transition frequency, anharmonicity (or nonlinearity), and susceptibility to noise.[34]

Of the three archetypes, phase qubits allow the most of Cooper pairs to tunnel through the junction, followed by flux qubits, and charge qubits allow the fewest.

Charge qubit

[edit]The charge qubit, also known as the Cooper pair box, possesses a Josephson to charging energy ratio on the order of magnitude . For charge qubits, different energy levels correspond to an integer number of Cooper pairs on a superconducting island (a small superconducting area with a controllable number of charge carriers).[36] Indeed, the first experimentally realized qubit was the Cooper pair box, achieved in 1999.[37]

Flux qubit

[edit]The flux qubit (also known as a persistent-current qubit) possesses a Josephson to charging energy ratio on the order of magnitude . For flux qubits, the energy levels correspond to different integer numbers of magnetic flux quanta trapped in a superconducting ring.

Phase qubit

[edit]The phase qubit possesses a Josephson to charge energy ratio on the order of magnitude . For phase qubits, energy levels correspond to different quantum charge oscillation amplitudes across a Josephson junction, where charge and phase are analogous to momentum and position respectively as analogous to a quantum harmonic oscillator. Note that in this context phase is the complex argument of the superconducting wave function (also known as the superconducting order parameter), not the phase between the different states of the qubit.

Type Aspect

|

Charge qubit | RF-SQUID qubit (prototype of the Flux Qubit) | Phase qubit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit |  |

|

|

| Hamiltonian |

In this case is the number of Cooper pairs to tunnel through the junction, is the charge on the capacitor in units of Cooper pairs number, is the charging energy associated with both capacitance and Josephson junction capacitance . |

Note that is only allowed to take values greater than and is alternatively defined as the time integral of voltage along inductance . |

Here is magnetic flux quantum. |

| Potential |  |

|

|

In the table above, the three superconducting qubit archetypes are reviewed. In the first row, the qubit's electrical circuit diagram is presented. The second row depicts a quantum Hamiltonian derived from the circuit. Generally, the Hamiltonian is the sum of the system's kinetic and potential energy components (analogous to a particle in a potential well). For the Hamiltonians denoted, is the superconducting wave function phase difference across the junction, is the capacitance associated with the Josephson junction, and is the charge on the junction capacitance. For each potential depicted, only solid wave functions are used for computation. The qubit potential is indicated by a thick red line, and schematic wave function solutions are depicted by thin lines, lifted to their appropriate energy level for clarity.

Note that particle mass corresponds to an inverse function of the circuit capacitance and that the shape of the potential is governed by regular inductors and Josephson junctions. Schematic wave solutions in the third row of the table show the complex amplitude of the phase variable. Specifically, if a qubit's phase is measured while the qubit occupies a particular state, there is a non-zero probability of measuring a specific value only where the depicted wave function oscillates. All three rows are essentially different presentations of the same physical system.

Hybridizations

[edit]While the three core forms of superconducting qubits (phase, charge, and flux) are historically how superconducting qubits were categorized, most modern superconducting qubits are a hybridization of these archetypes. Many hybridizations of these archetypes exist including the fluxonium,[39] transmon,[40] Xmon,[41] and quantronium.[42]

Transmon

[edit]Transmons are a special type of qubit with a shunted capacitor specifically designed to mitigate noise. The transmon qubit model a charge-phase hybrid qubit based on the Cooper pair box[44]. The increased ratio of Josephson to charge energy mitigates noise. The Hamiltonian for the transmon is:

where n is the number of Cooper pairs transferred between the island and is the phase difference across the junction.[45]

Two transmons can be coupled using a coupling capacitor.[2] For this 2-qubit system the Hamiltonian is written

- ,

where is current density and is surface charge density.[2]

Transmon qubits are the most popular design of modern superconducting qubits, and are implemented in superconducting quantum processors such as Google's Willow processor, a chip with 105 physical transmon qubits.[46] Other companies that use transmon qubits include IBM, Rigetti, and IQM.

The physical design of a transmon qubit can vary depending on the implementation. Common transmon designs include the "transmon cross" which is shaped like an X or cross, and the pad or "paddle transmon", which contains two paddles next to each other.

Transmon-like qubits

[edit]Many variations of the transmon design exist and are active areas of research. They aim to improve upon failings of the transmon design.

Xmon

[edit]

The Xmon is similar in design to a transmon in that it originated based on the planar transmon model.[48] An Xmon is essentially a tunable transmon. The major difference between transmon and Xmon qubits is the Xmon qubit is grounded with one of its capacitor pads.[49]

Gatemon

[edit]Another variation of the transmon qubit is the Gatemon. Like the Xmon, the Gatemon is a tunable variation of the transmon. The Gatemon is tunable via gate voltage.

Unimon

[edit]The Unimon consists of a single Josephson junction shunted by a linear inductor (possessing an inductance not depending on current) inside a (superconducting) resonator.[50] Unimons have increased anharmonicity and display faster operation time resulting in lower susceptibility to noise errors.[50] Unimon qubits also have decreased susceptibility to flux noise and complete insensitivity to dc charge noise.[35] However, unimon qubits have a limited tunability range.

The unimon qubit was first formulated in 2022 by researchers from IQM Quantum Computers, Aalto University, and VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, and is still largely in the research stages of design.[52]

Fluxonium

[edit]Fluxonium qubits are a specific type of flux qubit whose Josephson junction is shunted by a linear inductor of where .[53] In practice, the linear inductor is usually implemented by a Josephson junction array that is composed of a large number (can be often ) of large-sized Josephson junctions connected in a series. Under this condition, the Hamiltonian of a fluxonium can be written as:

- .

One important property of the fluxonium qubit is the longer qubit lifetime at the half flux sweet spot, which can exceed 1 millisecond.[53][54] Another crucial advantage of the fluxonium qubit when biased at the sweet spot is its large anharmonicity. In this context, anharmonicity refers to the unequal spacing of energy levels in a superconducting circuit. Large anharmonicity is beneficial because it allows fast local microwave control and mitigates spectral crowding problems, leading to better scalability.[55][56]

0-π qubit

[edit]The 0-π qubit is a protected qubit design where logical states are protected by circuit symmetry.[57] The logical states of the qubit are exponentially protected against relaxation and exponentially (first-order) protected to first order against dephasing due to charge (flux) noise. This ideal behavior, however, is not always realistic because it requires that parameter dispersion among nominally identical circuit elements vanishes.[58]

Operation and readout

[edit]Single qubits

[edit]The GHz energy gap between energy levels of a superconducting qubit is designed to be compatible with available electronic equipment, due to the terahertz gap (lack of equipment in the higher frequency band). The superconductor energy gap implies a top limit of operation below ~1THz beyond which Cooper pairs break, so energy level separation cannot be too high. On the other hand, energy level separation cannot be too small due to cooling considerations: a temperature of 1 K implies energy fluctuations of 20 GHz. Temperatures of tens of millikelvins are achieved in dilution refrigerators and allow qubit operation at a ~5 GHz energy level separation. Qubit energy level separation is frequently adjusted by controlling a dedicated bias current line, providing a "knob" to fine tune the qubit parameters.

Single qubit gates

[edit]

A single qubit gate is achieved by rotation in the Bloch sphere. Rotations between different energy levels of a single qubit are induced by microwave pulses sent to an antenna or transmission line coupled to the qubit with a frequency resonant with the energy separation between levels. Individual qubits may be addressed by a dedicated transmission line or by a shared one if the other qubits are off resonance. The axis of rotation is set by quadrature amplitude modulation of microwave pulse, while pulse length determines the angle of rotation.[59]

More formally (following the notation of [59]) for a driving signal

of frequency , a driven qubit Hamiltonian in a rotating wave approximation is

- ,

where is the qubit resonance and are Pauli matrices.

To implement a rotation about the axis, one can set and apply a microwave pulse at frequency for time . The resulting transformation is

- .

This is exactly the rotation operator by angle about the axis in the Bloch sphere. A rotation about the axis can be implemented in a similar way. Showing the two rotation operators is sufficient for satisfying universality as every single qubit unitary operator may be presented as (up to a global phase which is physically inconsequential) by a procedure known as the decomposition.[60] Setting results in the transformation

up to the global phase and is known as the NOT gate.

Multiple qubits

[edit]

The ability to couple qubits is essential for implementing 2-qubit gates. Coupling two qubits can be achieved by connecting both to an intermediate electrical coupling circuit. The circuit may be either a fixed element (such as a capacitor) or be controllable (like the DC-SQUID). In the first case, decoupling qubits during the time the gate is switched off is achieved by tuning qubits out of resonance one from another, making the energy gaps between their computational states different.[61] This approach is inherently limited to nearest-neighbor coupling since a physical electrical circuit must be laid out between connected qubits. Notably, D-Wave Systems' nearest-neighbor coupling achieves a highly connected unit cell of 8 qubits in Chimera graph configuration. Quantum algorithms typically require coupling between arbitrary qubits. Consequently, multiple swap operations are necessary, limiting the length of quantum computation possible before processor decoherence.

Heisenberg interactions

[edit]The Heisenberg model of interactions, written as

,

serves as the basis for analog quantum simulation of spin systems and the primitive for an expressive set of quantum gates, sometimes referred to as fermionic simulation (or fSim) gates. In superconducting circuits, this interaction model has been implemented using flux-tunable qubits with flux-tunable coupling,[62] allowing the demonstration of quantum supremacy.[63] In addition, it can also be realized in fixed-frequency qubits with fixed-coupling using microwave drives.[64] The fSim gate family encompasses arbitrary XY and ZZ two-qubit unitaries, including the iSWAP, the CZ, and the SWAP gates (see Quantum logic gate).

Quantum bus

[edit]Another method of coupling two or more qubits is by way of a quantum bus, by pairing qubits to this intermediate. A quantum bus is often implemented as a microwave cavity modeled by a quantum harmonic oscillator. Coupled qubits may be brought in and out of resonance with the bus and with each other, eliminating the nearest-neighbor limitation. Formalism describing coupling is cavity quantum electrodynamics. In cavity quantum electrodynamics, qubits are analogous to atoms interacting with an optical photon cavity with a difference of GHz (rather than the THz regime of electromagnetic radiation). Resonant excitation exchange among these artificial atoms is potentially useful for direct implementation of multi-qubit gates.[65] Following the dark state manifold, the Khazali-Mølmer scheme[65] performs complex multi-qubit operations in a single step, providing a substantial shortcut to the conventional circuit model.

Cross resonant gate

[edit]One popular gating mechanism uses two qubits and a bus, each tuned to different energy level separations. Applying microwave excitation to the first qubit, with a frequency resonant with the second qubit, causes a rotation of the second qubit. Rotation direction depends on the state of the first qubit, allowing a controlled phase gate construction.[66]

Following the notation of,[66] the drive Hamiltonian describing the excited system through the first qubit driving line is formally written

- ,

where is the shape of the microwave pulse in time, is resonance frequency of the second qubit, are the Pauli matrices, is the coupling coefficient between the two qubits via the resonator, is qubit detuning, is stray (unwanted) coupling between qubits, and is the reduced Planck constant. The time integral over determines the angle of rotation. Unwanted rotations from the first and third terms of the Hamiltonian can be compensated for with single qubit operations. The remaining component, combined with single qubit rotations, forms a basis for the su(4) Lie algebra.

Geometric phase gate

[edit]Higher levels (outside of the computational subspace) of a pair of coupled superconducting circuits can be used to induce a geometric phase on one of the computational states of the qubits. This leads to an entangling conditional phase shift of the relevant qubit states. This effect has been implemented by flux-tuning the qubit spectra [67] and by using selective microwave driving.[68] Off-resonant driving can be used to induce differential ac-Stark shift, allowing the implementation of all-microwave controlled-phase gates.[69]

Qubit readout

[edit]Architecture-specific readout, or measurement, mechanisms exist. Readout of a phase qubit is explained in the qubit archetypes table above. A flux qubit state is often read using an adjustable DC-SQUID magnetometer. States may also be measured using an electrometer.[2] A more general readout scheme includes a coupling to a microwave resonator, where resonance frequency of the resonator is dispersively shifted by the qubit state.[70][71] Multi-level systems (qudits) can be readout using electron shelving.[72]

Performance

[edit]Criteria for quantum computation

[edit]DiVincenzo's criteria

[edit]DiVincenzo's criteria is a list describing the requirements for a physical system to be capable of implementing a logical qubit. DiVincenzo's criteria is satisfied by superconducting quantum computing implementation. Much of the current development effort in superconducting quantum computing aims to achieve interconnect, control, and readout in the 3rd dimension with additional lithography layers. The list of DiVincenzo's criteria for a physical system to implement a logical qubit is satisfied by the implementation of superconducting qubits. Although DiVincenzo's criteria as originally proposed consists of five criteria required for physically implementing a quantum computer, the more complete list consists of seven criteria as it takes into account communication over a computer network capable of transmitting quantum information between computers, known as the "quantum internet". Therefore, the first five criteria ensure successful quantum computing, while the final two criteria allow for quantum communication.

- A scalable physical system with well characterized qubits. "Well characterized" implies that the Hamiltonian function must be well-defined (i.e. the energy eigenstates of the qubit should be able to be quantified). A "scalable system" indicates that this ability to regulate a qubit should be augmentable for multiple more qubits. However, as more qubits are implemented, it leads to an exponential increase in cost and other physical implementations which pale in comparison to the enhanced speed it may offer.[25] As superconducting qubits are fabricated on a chip, the many-qubit system is readily scalable. Qubits are allocated on the 2D surface of the chip. The demand for well characterized qubits is fulfilled with (a) qubit non-linearity (accessing only two of the available energy levels) and (b) accessing a single qubit at a time (rather than the entire many-qubit system) by way of per-qubit dedicated control lines and/or frequency separation, or tuning out, of different qubits.

- Ability to initialize the state of qubits to a simple fiducial state.[73] A fiducial state is one that is easily and consistently replicable and is useful in quantum computing as it may be used to guarantee the initial state of qubits. One simple way to initialize a superconducting qubit is to wait long enough for the qubits to relax to the ground state. Controlling qubit potential with tuning knobs allows faster initialization mechanisms.

- Long relevant decoherence times.[73] Decoherence of superconducting qubits is affected by multiple factors. Most decoherence is attributed to the quality of the Josephson junction and imperfections in the chip substrate. Due to their mesoscopic scale, superconducting qubits are relatively short lived. Nevertheless, thousands of gate operations have been demonstrated in these many-qubit systems.[74] Recent strategies to improve device coherence include purifying the circuit materials and designing qubits with decreased sensitivity to noise sources.[53]

- A "universal" set of quantum gates.[73] Superconducting qubits allow arbitrary rotations in the Bloch sphere with pulsed microwave signals, implementing single qubit gates. and couplings are shown for most implementations and for complementing the universal gate set.[75][76][64] This criterion may also be satisfied by coupling two transmons with a coupling capacitor.[2]

- Qubit-specific measurement ability.[73] In general, single superconducting qubits are used for control or for measurement.

- Interconvertibility of stationary and flying qubits.[73] While stationary qubits are used to store information or perform calculations, flying qubits transmit information macroscopically. Qubits should be capable of converting from being a stationary qubit to being a flying qubit and vice versa.

- Reliable transmission of flying qubits between specified locations.[73]

The final two criteria have been experimentally proven by research performed by ETH Zurich university with two superconducting qubits connected by a coaxial cable.[77]

Challenges

[edit]Many current challenges faced by superconducting quantum computing lie in the field of microwave engineering.[70] Some challenges in superconducting qubit design are shaping the potential well and choosing particle mass such that energy separation between two specific energy levels is unique, differing from all other interlevel energy separation in the system, since these two levels are used as logical states of the qubit. Other challenges are mitigating sources of noise in the system. Finally, even more challenges occur a result of scaling to larger and larger device sizes.

Noise

[edit]Superconducting quantum computing must mitigate quantum noise (disruptions of the system caused by its interaction with an environment) as well as leakage (information being lost to the surrounding environment). One way to reduce leakage is with parity measurements.[29] Another strategy is to use qubits with large anharmonicity.[55][56]

Two-level system (TLS) effects

[edit]Two-level system (TLS) effects are a dominant source of noise in superconducting qubits.[78][79] TLS act as resonant, two-level absorbers which drain energy from the qubit, significantly reducing coherence times. They are thought to be caused by deformities during the fabrication process, and surface amorphous oxides that form on or near Josephson junctions. Additionally, coherent TLS defects fluctuate in time, and at the moment, mitigating them requires full recalibration of quantum processors containing 100 qubits around once per day.[78] As the TLS density increases, it becomes harder to protect a system from TLS effects.[78]

Attempts to mitigate TLS effects include developing new fabrication techniques, and experimenting with new materials such as niobium and tantalum.[80]

Quasiparticles

[edit]

Quasiparticles are single-electron excitations that occur when Cooper pairs break. They consist of a superposition of an electron and an 'electron hole'. They occur when a Cooper pair is hit by a photon, causing it to break.[81] There are two kinds of particles; thermally-generated equilibrium quasiparticles, and non-equilibrium quasiparticles which get excited due to other effects in the system. While equilibrium quasiparticles can be suppressed exponentially by operating at low temperatures, but non-equilibrium quasiparticles, due to radiation such as gammas and cosmic ray muons, cannot.[81][82]

Attempts to mitigate quasiparticle generation include increasing shielding against radiation,[83] quasiparticle trapping, gap engineering,[84] or otherwise removing them from the system.[85]

Scaling

[edit]As superconducting quantum computing approaches larger scale devices, researchers face difficulties in qubit coherence, scalable calibration software, efficient determination of fidelity of quantum states across an entire chip, and qubit and gate fidelity.[29] Moreover, superconducting quantum computing devices must be reliably reproducible at increasingly large scales such that they are compatible with these improvements.[29]

References

[edit]- ^ "What is a qubit? | IBM". www.ibm.com. 2024-02-28. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b c d e f "PennyLane Documentation". docs.pennylane.ai. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ^ Qiskit (2022-09-28). "How The First Superconducting Qubit Changed Quantum Computing Forever". Qiskit. Retrieved 2026-02-15.

- ^ Castelvecchi, Davide (5 January 2017). "Quantum computers ready to leap out of the lab in 2017". Nature. 541 (7635): 9–10. Bibcode:2017Natur.541....9C. doi:10.1038/541009a. PMID 28054624. S2CID 4447373.

- ^ "IBM Makes Quantum Computing Available on IBM Cloud". www-03.ibm.com. 4 May 2016. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016.

- ^ "Imec enters the race to unleash quantum computing with silicon qubits". www.imec-int.com. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ Ryan, Colm A.; Johnson, Blake R.; Ristè, Diego; Donovan, Brian; Ohki, Thomas A. (2017). "Hardware for dynamic quantum computing". Review of Scientific Instruments. 88 (10) 104703. arXiv:1704.08314. Bibcode:2017RScI...88j4703R. doi:10.1063/1.5006525. PMID 29092485.

- ^ "Rigetti Launches Quantum Cloud Services, Announces $1Million Challenge". HPCwire. 2018-09-07. Retrieved 2018-09-16.

- ^ "Intel Invests US$50 Million to Advance Quantum Computing | Intel Newsroom". Intel Newsroom.

- ^ a b Qiskit (2022-09-28). "How The First Superconducting Qubit Changed Quantum Computing Forever". Qiskit. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan A. (2001-01-01). "Quantum computing and nuclear magnetic resonance". PhysChemComm. 4 (11): 49–56. doi:10.1039/B103231N. ISSN 1460-2733.

- ^ Nakamura, Y.; Pashkin, Yu A.; Tsai, J. S. (April 1999). "Coherent control of macroscopic quantum states in a single-Cooper-pair box". Nature. 398 (6730): 786–788. arXiv:cond-mat/9904003. Bibcode:1999Natur.398..786N. doi:10.1038/19718. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4392755.

- ^ Alicki, Robert (2006-06-29). "False qubits?: Polarization of light and Josephson junction". arXiv:quant-ph/0606242.

- ^ Bland, Matthew P.; Bahrami, Faranak; Martinez, Jeronimo G. C.; Prestegaard, Paal H.; Smitham, Basil M.; Joshi, Atharv; Hedrick, Elizabeth; Kumar, Shashwat; Yang, Ambrose; Pakpour-Tabrizi, Alexander C.; Jindal, Apoorv; Chang, Ray D.; Cheng, Guangming; Yao, Nan; Cava, Robert J. (November 2025). "Millisecond lifetimes and coherence times in 2D transmon qubits". Nature. 647 (8089): 343–348. Bibcode:2025Natur.647..343B. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09687-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 41193811.

- ^ "Our quantum computing journey". Google Quantum AI. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ^ Marin; Ivezic, Marin (2023-12-11). "IBM Unveils Condor: 1,121‑Qubit Quantum Processor". PostQuantum - Quantum Computing, Quantum Security, PQC. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "IBM Quantum System Two: the era of quantum utility is here | IBM Quantum Computing Blog". www.ibm.com. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Google's Willow Quantum Chip Crushes 3 Years of Supercomputer Work in 2 Hours: Bitcoin Encryption at Risk?". CCN.com. 2025-10-23. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Dayal, Geeta. "LEGO Turing Machine Is Simple, Yet Sublime". WIRED.

- ^ a b Ballon, Alvaro (22 March 2022). "Quantum computing with superconducting qubits — PennyLane". Pennylane Demos. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ^ Kwon, Sangil; Tomonaga, Akiyoshi; Lakshmi Bhai, Gopika; Devitt, Simon J.; Tsai, Jaw-Shen (2021-01-28). "Gate-based superconducting quantum computing". Journal of Applied Physics. 129 (4). doi:10.1063/5.0029735. ISSN 0021-8979. Archived from the original on 2025-12-08.

- ^ Fedorov, A.; Steffen, L.; Baur, M.; da Silva, M. P.; Wallraff, A. (2011-12-14). "Implementation of a Toffoli gate with superconducting circuits". Nature. 481 (7380): 170–172. doi:10.1038/nature10713. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 22170609.

- ^ a b c Kwon, Sangil; Tomonaga, Akiyoshi; Lakshmi Bhai, Gopika; Devitt, Simon J.; Tsai, Jaw-Shen (2021-01-28). "Gate-based superconducting quantum computing". Journal of Applied Physics. 129 (4). doi:10.1063/5.0029735. ISSN 0021-8979. Archived from the original on 2025-12-08.

- ^ Bertet, P.; Harmans, C. J. P. M.; Mooij, J. E. (2006-02-14). "Parametric coupling for superconducting qubits". Physical Review B. 73 (6). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.73.064512. ISSN 1098-0121. Archived from the original on 2025-08-28.

- ^ a b "DiVincenzo's Criteria – Quantum Computing Codex". qc-at-davis.github.io. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ^ Young, Margot. "Experimental Qubit Construction" (PDF).

- ^ "Cooper Pairs".

- ^ a b c d Martinis, John M.; Osborne, Kevin (2004-02-16). "Superconducting Qubits and the Physics of Josephson Junctions". arXiv:cond-mat/0402415.

- ^ a b c d e Kjaergaard, Morten; Schwartz, Mollie E.; Braumüller, Jochen; Krantz, Philip; Wang, Joel I.-Jan; Gustavsson, Simon; Oliver, William D. (2020-03-10). "Superconducting Qubits: Current State of Play". Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics. 11 (1): 369–395. arXiv:1905.13641. Bibcode:2020ARCMP..11..369K. doi:10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031119-050605. ISSN 1947-5454. S2CID 173188891.

- ^ Van Damme, J.; Massar, S.; Acharya, R.; Ivanov, Ts; Perez Lozano, D.; Canvel, Y.; Demarets, M.; Vangoidsenhoven, D.; Hermans, Y.; Lai, J. G.; Vadiraj, A. M.; Mongillo, M.; Wan, D.; De Boeck, J.; Potočnik, A. (October 2024). "Advanced CMOS manufacturing of superconducting qubits on 300 mm wafers". Nature. 634 (8032): 74–79. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07941-9. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Zwerver, A. M. J.; Krähenmann, T.; Watson, T. F.; Lampert, L.; George, H. C.; Pillarisetty, R.; Bojarski, S. A.; Amin, P.; Amitonov, S. V.; Boter, J. M.; Caudillo, R.; Correas-Serrano, D.; Dehollain, J. P.; Droulers, G.; Henry, E. M. (March 2022). "Qubits made by advanced semiconductor manufacturing". Nature Electronics. 5 (3): 184–190. doi:10.1038/s41928-022-00727-9. ISSN 2520-1131.

- ^ Shen, L. Y. L. (1972-02-01). "Superconductivity of Tantalum, Niobium and Lanthanum Studied by Electron Tunneling: Problems of Surface Contamination". AIP Conference Proceedings. 4 (1): 31–44. Bibcode:1972AIPC....4...31S. doi:10.1063/1.2946195. ISSN 0094-243X.

- ^ Alexander, Ashish; Weddle, Christopher G.; Richardson, Christopher J. K. (2025-09-01). "Power and temperature dependent model for high Q superconductor resonators". APL Quantum. 2 (3). doi:10.1063/5.0273506. ISSN 2835-0103.

- ^ Krantz, Philip; Kjaergaard, Morten; Yan, Fei; Orlando, Terry P.; Gustavsson, Simon; Oliver, William D. (2021-07-07). "A quantum engineer's guide to superconducting qubits". Applied Physics Reviews. 6 (2) 021318. arXiv:1904.06560. doi:10.1063/1.5089550.

- ^ a b c Hyyppä, Eric; Kundu, Suman; Chan, Chun Fai; Gunyhó, András; Hotari, Juho; Janzso, David; Juliusson, Kristinn; Kiuru, Olavi; Kotilahti, Janne; Landra, Alessandro; Liu, Wei; Marxer, Fabian; Mäkinen, Akseli; Orgiazzi, Jean-Luc; Palma, Mario (2022-11-12). "Unimon qubit". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 6895. arXiv:2203.05896. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.6895H. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34614-w. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9653402. PMID 36371435.

- ^ "Superconducting qubits – on islands, charge qubits and the transmon". LeftAsExercise. 2019-06-06. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ Wendin, G. (2017-10-01). "Quantum information processing with superconducting circuits: a review". Reports on Progress in Physics. 80 (10): 106001. arXiv:1610.02208. Bibcode:2017RPPh...80j6001W. doi:10.1088/1361-6633/aa7e1a. ISSN 0034-4885. PMID 28682303. S2CID 3940479.

- ^ Devoret, M. H.; Wallraff, A.; Martinis, J. M. (6 November 2004). "Superconducting Qubits: A Short Review". arXiv:cond-mat/0411174.

- ^ Manucharyan, V. E.; Koch, J.; Glazman, L. I.; Devoret, M. H. (1 October 2009). "Fluxonium: Single Cooper-Pair Circuit Free of Charge Offsets". Science. 326 (5949): 113–116. arXiv:0906.0831. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..113M. doi:10.1126/science.1175552. PMID 19797655. S2CID 17645288.

- ^ Houck, A. A.; Koch, Jens; Devoret, M. H.; Girvin, S. M.; Schoelkopf, R. J. (11 February 2009). "Life after charge noise: recent results with transmon qubits". Quantum Information Processing. 8 (2–3): 105–115. arXiv:0812.1865. Bibcode:2009QuIP....8..105H. doi:10.1007/s11128-009-0100-6. S2CID 27305073.

- ^ Barends, R.; Kelly, J.; Megrant, A.; Sank, D.; Jeffrey, E.; Chen, Y.; Yin, Y.; Chiaro, B.; Mutus, J.; Neill, C.; O'Malley, P.; Roushan, P.; Wenner, J.; White, T. C.; Cleland, A. N.; Martinis, John M. (22 August 2013). "Coherent Josephson Qubit Suitable for Scalable Quantum Integrated Circuits". Physical Review Letters. 111 (8) 080502. arXiv:1304.2322. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.111h0502B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.080502. PMID 24010421. S2CID 27081288.

- ^ Metcalfe, M.; Boaknin, E.; Manucharyan, V.; Vijay, R.; Siddiqi, I.; Rigetti, C.; Frunzio, L.; Schoelkopf, R. J.; Devoret, M. H. (21 November 2007). "Measuring the decoherence of a quantronium qubit with the cavity bifurcation amplifier". Physical Review B. 76 (17) 174516. arXiv:0706.0765. Bibcode:2007PhRvB..76q4516M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.76.174516. S2CID 19088840.

- ^ Gambetta, J. M.; Chow, J. M.; Steffen, M. (2017). "Building logical qubits in a superconducting quantum computing system". npj Quantum Information. 3 (1): 2. arXiv:1510.04375. Bibcode:2017npjQI...3....2G. doi:10.1038/s41534-016-0004-0.

- ^ Roth, Thomas E.; Ma, Ruichao; Chew, Weng C. (2023). "The Transmon Qubit for Electromagnetics Engineers: An introduction". IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine. 65 (2): 8–20. arXiv:2106.11352. Bibcode:2023IAPM...65b...8R. doi:10.1109/MAP.2022.3176593.

- ^ Koch, Jens; Yu, Terri M.; Gambetta, Jay; Houck, A. A.; Schuster, D. I.; Majer, J.; Blais, Alexandre; Devoret, M. H.; Girvin, S. M. (2007-09-26). "Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the Cooper pair box". Physical Review A. 76 (4) 042319. arXiv:cond-mat/0703002. Bibcode:2007PhRvA..76d2319K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.76.042319.

- ^ "Google's quantum breakthrough is 'truly remarkable' - but there's more to do". ZDNET. Retrieved 2026-01-07.

- ^ Fig. 1: Unimon qubit and its measurement setup from Hyyppä, Eric; Kundu, Suman; Chan, Chun Fai; Gunyhó, András; Hotari, Juho; Janzso, David; Juliusson, Kristinn; Kiuru, Olavi; Kotilahti, Janne; Landra, Alessandro; Liu, Wei; Marxer, Fabian; Mäkinen, Akseli; Orgiazzi, Jean-Luc; Palma, Mario; Savytskyi, Mykhailo; Tosto, Francesca; Tuorila, Jani; Vadimov, Vasilii; Li, Tianyi; Ockeloen-Korppi, Caspar; Heinsoo, Johannes; Tan, Kuan Yen; Hassel, Juha; Möttönen, Mikko (12 November 2022). "Unimon qubit". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 6895. arXiv:2203.05896. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.6895H. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34614-w. PMC 9653402. PMID 36371435.

- ^ Shim, Yun-Pil; Tahan, Charles (2016-03-17). "Semiconductor-inspired design principles for superconducting quantum computing". Nature Communications. 7 (1) 11059. arXiv:1507.07923. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711059S. doi:10.1038/ncomms11059. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4800439. PMID 26983379.

- ^ Wang, Chenlu; Li, Xuegang; Xu, Huikai; Li, Zhiyuan; Wang, Junhua; Yang, Zhen; Mi, Zhenyu; Liang, Xuehui; Su, Tang; Yang, Chuhong; Wang, Guangyue; Wang, Wenyan; Li, Yongchao; Chen, Mo; Li, Chengyao (2022-01-13). "Towards practical quantum computers: transmon qubit with a lifetime approaching 0.5 milliseconds". npj Quantum Information. 8 (1): 3. arXiv:2105.09890. Bibcode:2022npjQI...8....3W. doi:10.1038/s41534-021-00510-2. ISSN 2056-6387. S2CID 245950831.

- ^ a b Buchanan, Mark (2022-12-08). "Meet the Unimon, the New Qubit on the Block". Physics. 15 191. Bibcode:2022PhyOJ..15..191B. doi:10.1103/Physics.15.191. S2CID 257514449.

- ^ a b Cottet, Nathanaël; Xiong, Haonan; Nguyen, Long B.; Lin, Yen-Hsiang; Manucharyan, Vladimir E. (2021-11-04). "Electron shelving of a superconducting artificial atom". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 6383. arXiv:2008.02423. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.6383C. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26686-x. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8569191. PMID 34737313.

- ^ "Unimon: A new qubit to boost quantum computers from IQM". www.meetiqm.com. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ a b c Nguyen, Long B.; Lin, Yen-Hsiang; Somoroff, Aaron; Mencia, Raymond; Grabon, Nicholas; Manucharyan, Vladimir E. (25 November 2019). "High-Coherence Fluxonium Qubit". Physical Review X. 9 (4) 041041. arXiv:1810.11006. Bibcode:2019PhRvX...9d1041N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.9.041041. ISSN 2160-3308. S2CID 53499609.

- ^ Science, The National University of; MISIS, Technology. "Fluxonium qubits bring the creation of a quantum computer closer". phys.org. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ a b Nguyen, Long B. (2020). Toward the Fluxonium Quantum Processor (Ph.D. thesis). University of Maryland, College Park. ProQuest 2455525166.

- ^ a b Nguyen, Long B.; Koolstra, Gerwin; Kim, Yosep; Morvan, Alexis; Chistolini, Trevor; Singh, Shraddha; Nesterov, Konstantin N.; Jünger, Christian; Chen, Larry; Pedramrazi, Zahra; Mitchell, Bradley K.; Kreikebaum, John Mark; Puri, Shruti; Santiago, David I.; Siddiqi, Irfan (5 August 2022). "Blueprint for a High-Performance Fluxonium Quantum Processor". PRX Quantum. 3 (3) 037001. arXiv:2201.09374. Bibcode:2022PRXQ....3c7001N. doi:10.1103/PRXQuantum.3.037001.

- ^ Gyenis, András; Mundada, Pranav S.; Di Paolo, Agustin; Hazard, Thomas M.; You, Xinyuan; Schuster, David I.; Koch, Jens; Blais, Alexandre; Houck, Andrew A. (2021-03-05). "Experimental Realization of a Protected Superconducting Circuit Derived from the 0 – π Qubit". PRX Quantum. 2 (1) 010339. doi:10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.010339. ISSN 2691-3399.

- ^ Groszkowski, Peter; Paolo, A. Di; Grimsmo, A. L.; Blais, A.; Schuster, D. I.; Houck, A. A.; Koch, Jens (2017-08-09). "Coherence properties of the 0- π qubit". New Journal of Physics. 20 (4): 043053. arXiv:1708.02886. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/aab7cd.

- ^ a b Motzoi, F.; Gambetta, J. M.; Rebentrost, P.; Wilhelm, F. K. (8 September 2009). "Simple Pulses for Elimination of Leakage in Weakly Nonlinear Qubits". Physical Review Letters. 103 (11) 110501. arXiv:0901.0534. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.103k0501M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.110501. PMID 19792356. S2CID 7288207.

- ^ Chuang, Michael A. Nielsen & Isaac L. (2010). Quantum computation and quantum information (10th anniversary ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 174–176. ISBN 978-1-107-00217-3.

- ^ Rigetti, Chad Tyler (2009). Quantum gates for superconducting qubits. p. 21. Bibcode:2009PhDT........50R. ISBN 978-1-109-19887-4.

- ^ Foxen, B.; Neill, C.; Dunsworth, A.; Roushan, P.; Chiaro, B.; Megrant, A.; Kelly, J.; Chen, Zijun; Satzinger, K.; Barends, R.; Arute, F.; Arya, K.; Babbush, R.; Bacon, D.; Bardin, J. C.; Boixo, S.; Buell, D.; Burkett, B.; Chen, Yu; Collins, R.; Farhi, E.; Fowler, A.; Gidney, C.; Giustina, M.; Graff, R.; Harrigan, M.; Huang, T.; Isakov, S. V.; Jeffrey, E.; Jiang, Z.; Kafri, D.; Kechedzhi, K.; Klimov, P.; Korotkov, A.; Kostritsa, F.; Landhuis, D.; Lucero, E.; McClean, J.; McEwen, M.; Mi, X.; Mohseni, M.; Mutus, J. Y.; Naaman, O.; Neeley, M.; Niu, M.; Petukhov, A.; Quintana, C.; Rubin, N.; Sank, D.; Smelyanskiy, V.; Vainsencher, A.; White, T. C.; Yao, Z.; Yeh, P.; Zalcman, A.; Neven, H.; Martinis, J. M.; et al. (Google AI Quantum) (2020-09-15). "Demonstrating a Continuous Set of Two-qubit Gates for Near-term Quantum Algorithms". Physical Review Letters. 125 (12) 120504. arXiv:2001.08343. Bibcode:2020PhRvL.125l0504F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.120504. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 33016760.

- ^ Arute, Frank; Arya, Kunal; Babbush, Ryan; Bacon, Dave; Bardin, Joseph C.; Barends, Rami; Biswas, Rupak; Boixo, Sergio; Brandao, Fernando G. S. L.; Buell, David A.; Burkett, Brian; Chen, Yu; Chen, Zijun; Chiaro, Ben; Collins, Roberto; Courtney, William; Dunsworth, Andrew; Farhi, Edward; Foxen, Brooks; Fowler, Austin; Gidney, Craig; Giustina, Marissa; Graff, Rob; Guerin, Keith; Habegger, Steve; Harrigan, Matthew P.; Hartmann, Michael J.; Ho, Alan; Hoffmann, Markus; Huang, Trent; Humble, Travis S.; Isakov, Sergei V.; Jeffrey, Evan; Jiang, Zhang; Kafri, Dvir; Kechedzhi, Kostyantyn; Kelly, Julian; Klimov, Paul V.; Knysh, Sergey; Korotkov, Alexander; Kostritsa, Fedor; Landhuis, David; Lindmark, Mike; Lucero, Erik; Lyakh, Dmitry; Mandrà, Salvatore; McClean, Jarrod R.; McEwen, Matthew; Megrant, Anthony; Mi, Xiao; Michielsen, Kristel; Mohseni, Masoud; Mutus, Josh; Naaman, Ofer; Neeley, Matthew; Neill, Charles; Niu, Murphy Yuezhen; Ostby, Eric; Petukhov, Andre; Platt, John C.; Quintana, Chris; Rieffel, Eleanor G.; Roushan, Pedram; Rubin, Nicholas C.; Sank, Daniel; Satzinger, Kevin J.; Smelyanskiy, Vadim; Sung, Kevin J.; Trevithick, Matthew D.; Vainsencher, Amit; Villalonga, Benjamin; White, Theodore; Yao, Z. Jamie; Yeh, Ping; Zalcman, Adam; Neven, Hartmut; Martinis, John M. (2019-10-23). "Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor". Nature. 574 (7779). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 505–510. arXiv:1910.11333. Bibcode:2019Natur.574..505A. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1666-5. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 31645734.

- ^ a b Nguyen, L.B.; Kim, Y.; Hashim, A.; Goss, N.; Marinelli, B.; Bhandari, B.; Das, D.; Naik, R.K.; Kreikebaum, J.M.; Jordan, A.; Santiago, D.I.; Siddiqi, I. (16 January 2024). "Programmable Heisenberg interactions between Floquet qubits". Nature Physics. 20 (1): 240–246. arXiv:2211.10383. Bibcode:2024NatPh..20..240N. doi:10.1038/s41567-023-02326-7.

- ^ a b Khazali, Mohammadsadegh; Mølmer, Klaus (2020-06-11). "Fast Multiqubit Gates by Adiabatic Evolution in Interacting Excited-State Manifolds of Rydberg Atoms and Superconducting Circuits". Physical Review X. 10 (2) 021054. arXiv:2006.07035. Bibcode:2020PhRvX..10b1054K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.10.021054. ISSN 2160-3308.

- ^ a b Chow, Jerry M.; Córcoles, A. D.; Gambetta, Jay M.; Rigetti, Chad; Johnson, B. R.; Smolin, John A.; Rozen, J. R.; Keefe, George A.; Rothwell, Mary B.; Ketchen, Mark B.; Steffen, M. (17 August 2011). "Simple All-Microwave Entangling Gate for Fixed-Frequency Superconducting Qubits". Physical Review Letters. 107 (8) 080502. arXiv:1106.0553. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.107h0502C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.080502. PMID 21929152. S2CID 9302474.

- ^ DiCarlo, L.; Chow, J. M.; Gambetta, J. M.; Bishop, Lev S.; Johnson, B. R.; Schuster, D. I.; Majer, J.; Blais, A.; Frunzio, L.; Girvin, S. M.; Schoelkopf, R. J. (2009-06-28). "Demonstration of two-qubit algorithms with a superconducting quantum processor". Nature. 460 (7252). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 240–244. arXiv:0903.2030. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..240D. doi:10.1038/nature08121. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 19561592.

- ^ Ficheux, Quentin; Nguyen, Long B.; Somoroff, Aaron; Xiong, Haonan; Nesterov, Konstantin N.; Vavilov, Maxim G.; Manucharyan, Vladimir E. (2021-05-03). "Fast Logic with Slow Qubits: Microwave-Activated Controlled-Z Gate on Low-Frequency Fluxoniums". Physical Review X. 11 (2) 021026. arXiv:2011.02634. Bibcode:2021PhRvX..11b1026F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.11.021026. ISSN 2160-3308.

- ^ Xiong, Haonan; Ficheux, Quentin; Somoroff, Aaron; Nguyen, Long B.; Dogan, Ebru; Rosenstock, Dario; Wang, Chen; Nesterov, Konstantin N.; Vavilov, Maxim G.; Manucharyan, Vladimir E. (2022-04-15). "Arbitrary controlled-phase gate on fluxonium qubits using differential ac Stark shifts". Physical Review Research. 4 (2) 023040. arXiv:2103.04491. Bibcode:2022PhRvR...4b3040X. doi:10.1103/PhysRevResearch.4.023040. ISSN 2643-1564.

- ^ a b Gambetta, Jay M.; Chow, Jerry M.; Steffen, Matthias (13 January 2017). "Building logical qubits in a superconducting quantum computing system". npj Quantum Information. 3 (1): 2. arXiv:1510.04375. Bibcode:2017npjQI...3....2G. doi:10.1038/s41534-016-0004-0.

- ^ Blais, Alexandre; Huang, Ren-Shou; Wallraff, Andreas; Girvin, Steven; Schoelkopf, Robert (2004). "Cavity quantum electrodynamics for superconducting electrical circuits: An architecture for quantum computation". Phys. Rev. A. 69 (6) 062320. arXiv:cond-mat/0402216. Bibcode:2004PhRvA..69f2320B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.69.062320. S2CID 20427333.

- ^ Cottet, Nathanaël; Xiong, Haonan; Nguyen, Long B.; Lin, Yen-Hsiang; Manucharyan, Vladimir E. (2021-11-04). "Electron shelving of a superconducting artificial atom". Nature Communications. 12 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 6383. arXiv:2008.02423. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.6383C. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26686-x. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8569191. PMID 34737313.

- ^ a b c d e f DiVincenzo, David (February 1, 2008). "The Physical Implementation of Quantum Computation". IBM T.J. Watson Research Center. 48 (9–11): 771–783. arXiv:quant-ph/0002077. Bibcode:2000ForPh..48..771D. doi:10.1002/1521-3978(200009)48:9/11<771::AID-PROP771>3.0.CO;2-E. S2CID 15439711.

- ^ Devoret, M. H.; Schoelkopf, R. J. (7 March 2013). "Superconducting Circuits for Quantum Information: An Outlook". Science. 339 (6124): 1169–1174. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1169D. doi:10.1126/science.1231930. PMID 23471399. S2CID 10123022.

- ^ Chow, Jerry M.; Gambetta, Jay M.; Córcoles, A. D.; Merkel, Seth T.; Smolin, John A.; Rigetti, Chad; Poletto, S.; Keefe, George A.; Rothwell, Mary B.; Rozen, J. R.; Ketchen, Mark B.; Steffen, M. (9 August 2012). "Universal Quantum Gate Set Approaching Fault-Tolerant Thresholds with Superconducting Qubits". Physical Review Letters. 109 (6) 060501. arXiv:1202.5344. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.109f0501C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.060501. PMID 23006254. S2CID 39874288.

- ^ Niskanen, A. O.; Harrabi, K.; Yoshihara, F.; Nakamura, Y.; Lloyd, S.; Tsai, J. S. (4 May 2007). "Quantum Coherent Tunable Coupling of Superconducting Qubits". Science. 316 (5825): 723–726. Bibcode:2007Sci...316..723N. doi:10.1126/science.1141324. PMID 17478714. S2CID 43175104.

- ^ Morsch, Oliver; Zurich, E. T. H. "Quantum transfer at the push of a button". phys.org. Retrieved 2022-12-09.

- ^ a b c Mohseni, Masoud; Scherer, Artur; Johnson, K. Grace; Wertheim, Oded; Otten, Matthew; Aadit, Navid Anjum; Alexeev, Yuri; Bresniker, Kirk M.; Camsari, Kerem Y. (2025-01-31). "How to Build a Quantum Supercomputer: Scaling from Hundreds to Millions of Qubits". arXiv:2411.10406 [quant-ph].

- ^ Thorbeck, Ted; Eddins, Andrew; Lauer, Isaac; McClure, Douglas T.; Carroll, Malcolm (2022-10-10). "Two-Level-System Dynamics in a Superconducting Qubit Due to Background Ionizing Radiation". PRX Quantum. 4 (2) 020356. arXiv:2210.04780v1. doi:10.1103/PRXQuantum.4.020356.

- ^ Oh, Jin-Su; Zaman, Rahim; Murthy, Akshay A.; Bal, Mustafa; Crisa, Francesco; Zhu, Shaojiang; Torres-Castendo, Carlos G.; Kopas, Cameron J.; Mutus, Joshua Y.; Jing, Dapeng; Zasadzinski, John; Grassellino, Anna; Romanenko, Alex; Hersam, Mark C.; Bedzyk, Michael J. (2024-07-21). "Structure and Formation Mechanisms in Tantalum and Niobium Oxides in Superconducting Quantum Circuits". ACS Nano. 18 (30) acsnano.4c05251. doi:10.1021/acsnano.4c05251. ISSN 1936-0851. PMC 11295204. PMID 39034612.

- ^ a b Pan, Xianchuang; Zhou, Yuxuan; Yuan, Haolan; Nie, Lifu; Wei, Weiwei; Zhang, Libo; Li, Jian; Liu, Song; Jiang, Zhi Hao; Catelani, Gianluigi; Hu, Ling; Yan, Fei; Yu, Dapeng (2022-11-23). "Engineering superconducting qubits to reduce quasiparticles and charge noise". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 7196. arXiv:2202.01435. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.7196P. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34727-2. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9684549. PMID 36418286.

- ^ Iaia, Vito; Ku, Jaseung; Ballard, Andrew; Liu, Chuan-Hong; McDermott, Robert; Plourde, B. L. T. (March 2022). "Mitigation of quasiparticle poisoning in superconducting qubits using normal metal backside metallization". APS March Meeting Abstracts. 2022: M41.010. Bibcode:2022APS..MARM41010I.

- ^ Pan, Xianchuang; Zhou, Yuxuan; Yuan, Haolan; Nie, Lifu; Wei, Weiwei; Zhang, Libo; Li, Jian; Liu, Song; Jiang, Zhi Hao; Catelani, Gianluigi; Hu, Ling; Yan, Fei; Yu, Dapeng (2022-11-23). "Engineering superconducting qubits to reduce quasiparticles and charge noise". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 7196. arXiv:2202.01435. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.7196P. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34727-2. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9684549. PMID 36418286.

- ^ McEwen, Matt; Miao, Kevin C.; Atalaya, Juan; Bilmes, Alex; Crook, Alex; Bovaird, Jenna; Kreikebaum, John Mark; Zobrist, Nicholas; Jeffrey, Evan (2024-02-23). "Resisting High-Energy Impact Events through Gap Engineering in Superconducting Qubit Arrays". Physical Review Letters. 133 (24) 240601. arXiv:2402.15644. Bibcode:2024PhRvL.133x0601M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.133.240601. PMID 39750363.

- ^ Bargerbos, Arno; Splitthoff, Lukas Johannes; Pita-Vidal, Marta; Wesdorp, Jaap J.; Liu, Yu; Krogstrup, Peter; Kouwenhoven, Leo P.; Andersen, Christian Kraglund; Grünhaupt, Lukas (2023-02-06). "Mitigation of Quasiparticle Loss in Superconducting Qubits by Phonon Scattering". Physical Review Applied. 19 (2) 024014. arXiv:2207.12754. Bibcode:2023PhRvP..19b4014B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.19.024014. ISSN 2331-7019. Archived from the original on 2025-06-26.

Further reading

[edit]- Stancil, Daniel D.; Byrd, Gregory T. (2022). Principles of Superconducting Quantum Computers (1st ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-75072-7. OCLC 1302334194. 978-1-119-75074-1 (ebook).

- Salari, Alan (2024). Microwave Techniques in Superconducting Quantum Computers (Unabridged edition). Boston, Massachusetts: Artech House. ISBN 978-1-63081-987-3. OCLC 1405187817. 978-1-63081-988-0 (ebook).

- Krylov, Gleb; Jabbari, Tahereh; Friedman, Eby G. (2024). Single Flux Quantum Integrated Circuit Design (Second Edition). Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-47475-0. ISBN 978-3-031-47474-3. OCLC 1430662174.

- Absar, Rubaya; Elgabra, Hazem; Ma, Dylan; Zhao, Yiju; Wei, Lan (2024). "Cryogenic CMOS for Quantum Computing". In Liu, Weiqiang; Han, Jie; Lombardi, Fabrizio (eds.). Design and Applications of Emerging Computer Systems (1st ed.). Cham: Springer. pp. 591–621. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-42478-6_22. ISBN 978-3-031-42478-6. OCLC 1418721165.

- Awan, Shakil; Kibble, Bryan P.; Schurr, Jürgen (2011). Coaxial Electrical Circuits for Interference-Free Measurements. Electrical Measurement Series 13. Stevenage: The Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET). doi:10.1049/PBEL013E. ISBN 978-1-84919-069-5. OCLC 761013886.

- Jordan, Andrew N.; Siddiqi, Irfan A. (2024). Quantum Measurement: Theory and Practice (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-10006-9. OCLC 1435711501.

- Zagoskin, Alexandre M. (2011). Quantum Engineering: Theory and Design of Quantum Coherent Structures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11369-4. OCLC 768771210.

- Van Duzer, Theodore; Turner, Charles W. (1999). Principles of Superconductive Devices and Circuits (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-262742-9. OCLC 40251418.

- Solymar, Lazlo (1972). Superconductive Tunnelling and Applications. London, England: Chapman and Hall. ISBN 0-412-10210-2. OCLC 488903.

External links

[edit]- IBM Quantum offers access to over 20 quantum computer systems.

- The IBM Quantum Experience offers free access to writing quantum algorithms and executing them on 5 qubit quantum computers.

- IBM's roadmap for quantum computing shows 65 qubit systems available in 2020 and 127 qubits to be available sometime in 2021.

![{\displaystyle H={\frac {q^{2}}{2C_{J}}}+\left({\frac {\Phi _{0}}{2\pi }}\right)^{2}{\frac {\phi ^{2}}{2L}}-E_{J}\cos \left[\phi -\Phi {\frac {2\pi }{\Phi _{0}}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9b3c5db999d2a0fde724d1e815fbac35572f361d)

![{\displaystyle U=\left({\frac {\Phi _{0}}{2\pi }}\right)^{2}{\frac {\phi ^{2}}{2L}}-E_{J}\cos \left[\phi -\Phi {\frac {2\pi }{\Phi _{0}}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7e2b2fa9a4a367c33d2bb107cc32c96461cb75f0)

![{\displaystyle |0\rangle =\left[|\circlearrowleft \rangle +|\circlearrowright \rangle \right]/{\sqrt {2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cfffbe4bb3e94a4fbec656181c73ee505a27c0a6)

![{\displaystyle |1\rangle =\left[|\circlearrowleft \rangle -|\circlearrowright \rangle \right]/{\sqrt {2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/98e896ffa7e728ae37d890b2bd7fd3bae48779af)