ጊዜ

ጊዜ ኩነቶችን (ክስተቶችን) ለመደርደር፣ ቆይታቸውን ለማነጻጻር፣ በመካከላቸውም ያለፈውን ቆይታ ለመወሰን በተረፈም የነገሮችን እንቅስቃሴ መጠን ለመለካት የሚያገለግል ነገር ነው። ጊዜ በፍልስፍና፣ ሃይማኖት፣ ሳይንስ ውስጥ ብዙ ጥናት የተካሄደበት ጽንሰ ሃሳብ ቢሆንም ቅሉ እስካሁን ድረስ በሁሉ ቦታ ለሁሉ የሚሰራ ትርጓሜ አልተገኘለትም።

የጊዜ መተግበሪያ ትርጉም ለዕለት ተለት ኑሮ ጠቃሚነቱ ስለታመነበት ከዘመናት በፊት ጀምሮ እስካሁን ይሰራበታል። ይህ መተግበሪያ ትርጉም ለምሳሌ ሰከንድን በመተርጎም ይጀምራል። ማለት በቋሚ ድግግሞሽ የሚፈጠሩ ኩነቶችን/ክስተቶችን በማስተዋል የተወሰነ ድግግማቸውን አንድ ሰከንድ ነው ብሎ በማወጅ የመተግበሪያ ትርጉሙ (ለስራ የሚያመች ትርጉሙ) ይነሳል። ለምሳሌ የልብ ተደጋጋሚ ምት፣ የፔንዱለም ውዝዋዜ ወይም ደግሞ የቀኑ መሽቶ-ነግቶ-መምሸት ወዘተ.. እነዚህ ኩነቶች እራሳቸውን በቋሚነት ስለሚደጋግሙ ከነሱ በመነሳት ሰዓትንና ደቂቃን ማወጅ ይቻላል (መሽቶ ሲነጋ 24 ሰዓት ነው፣ ልብ ሲመታ ወይም ፔንዱለም አንድ ጊዜ ሄዶ ሲመለስ አንድ ሰኮንድ ነው፣ ወዘተ..) ። የመተግበሪያ ትርጉሙ ተግባራዊ ጥቅም ይኑረው እንጂ «ጊዜ በራሱ ምንድን ነው?» ፣ ወይም ደግሞ «ጊዜ አለ ወይ?» ወይም ደግሞ «ጊዜ የሚባል ነገር በራሱ አለ ወይ?» ለሚሉት ጥያቄወች መልስ አይሰጥም።

በአሁኑ ወቅት ጊዜ በሁለት አይነት መንገድ ይታያል፦

- 1. አንደኛው አስተሳሰብ ጊዜ ማለት የውኑ አለም መሰረታዊ ክፍል ሲሆን፣ ማንኛውም ኩነት (event) የሚፈጠርበት ቅጥ ነው። እንግሊዛዊው ሳይንቲስት ኢሳቅ ኒውተን ይህን አስተያየት ስለደገፈ ኒውተናዊ ጊዜ ተብሎ ይታወቃል [1][2] ጊዜ እንግዲህ ባዶ አቃፊ ነገር ሲሆን ኩነቶች በዚህ ባዶ አቃፊ ነገር ውስጥ ይደረደራሉ ማለት ነው። መስተዋል ያለበት ይህ ጊዜ የተባለው አቃፊ ነገር ኩነቶች ኖሩ አልኖሩ ምንግዜም ህልው ነው።

- 2. ከላይ የተጠቀሰውን የጊዜ ጽንሰ ሃሳብ የሚቃወም አስተያየት ሁለተኛው አስተያየት ሲሆን ማንኛውንም አይነት «አቃፊ» የተባለ የጊዜ ትርጉምን ይክዳል፣ እንዲሁም ቁስ አካሎች በዚህ «ጊዜ» በሚባል አቃፊ ነገር ውስጥ መንቀሳቀሳቸውን ይክዳል፣ የጊዜ ፍሰት አለ የሚለውን አስተሳሰብንም ያወጋዛል። ይልቁኑ በዚ በሁለተኛው አስተያየት ጊዜ ማለት አእምሮአችን የውኑን አለም ለመረዳት ከፈጠራቸው ህንጻወች (ቁጥርንና ኅዋን ጨምሮ) አንዱ ሲሆን ሰወች ኩኔቶችን ለመደረደር እና ለማነጻጸር የሚረዳቸው ምናባዊ መዋቅር ነው ይላል። ይህን ሃሳብ ካንጸባረቁት ውስጥ ሌብኒትዝና [3]ካንት,[4][5] ይገኙበታል። ካንት እንዳስተዋለ፦ ጊዜ ማለት ኩኔትም ሆነ ነገር አይደለም ስለዚህም ጊዜን መለካትም ሆነ በጊዜ ውስጥ መጓዝ አይቻልም ።

ሳይንቲስቶችና ቴክኖሎጂስቶች ጊዜን በሰዓት ለመለካት ብዙ ጥረት አድርገዋል። ይህ ጥረት ለከዋክብት ጥናትና ለተለያዩ ያለም ዙሪያ ጉዞወች እንደመነሳሻ ረድቷል። በቋሚ መንገድ እራሳቸውን የሚደጋግሙ ክስተቶች/ኩነቶች ከጥንት ጀምሮ ጊዜን ለመልካት አገልግለዋል። ለምሳሌ ጸሃይ በሰማይ ላይ የምታደርገው ጉዞ (ቀን)፣ የጨረቃ ቅርጾች(ወር)፣ የወቅቶች መፈራረቅ(ዓመት)፣ የፔንዱለም መወዛወዝ (ሰኮንድ) ወዘተ...ይገኙበታል። በአሁኑ ጊዜ ሰኮንድ የምትለካው የሴሲየም አረር ሲወራጭ በሚያሳየው ቋሚ ድግግሞሽ ነው።

ሬይ ከሚንግ የተባለው ልብ ወለድ ጸሃፊ በ1920 ስለ ጊዜ ሲጽፍ " ሁሉ ነገር በአንድ ጊዜ እንዳይፈጸም የሚያደርገው ነገር....ጊዜ ነው " በማለት እስካሁን ድረስ ታዋቂ የሆነችውን ጥቅስ መዝግቦ አልፏል,[6] ይቺ አባባል በብዙ ሳይንቲስቶችም ስትስተጋባ ተሰምታለች፣ ለምሳሌ በኦቨርቤክ,[7] እና ጆን ዊለር.[8][9]

ጊዜአዊ ጊዜ አለካክ ሁለት መልኮች አሉት እነሱም፡ ካሌንደር ና ሰዓት ናቸው። ካሌንደር የሂሳብ ንጥር ሲሆን ሰፋ ያለ ጊዜን ለመለካት የሚጠቅመን ነው። [10] ሰዓት ደግሞ በተጨባጭ ቁሶች ተጠቅመን የጊዜን ሂደት የምንልካበት ነው። በቀን ተቀን ኑሯችን ከአንድ ቀን ያነሰን ጊዜ ለመለካት ሰዓት ስንጠቀም ከዚያ በላይ የሆነውን ደግሞ በካሌንደር እንለካለን።

ኦግስጢን የተባለው የካቶሊክ ፈላስፋ "ጊዜ ምንድን ነው?" በማለት እራሱን መጠየቁን በመጽሃፉ አስፍሯል። ሲመልስም "ሌላ ማንም ካልጠየቀኝ መልሱን አውቀዋለሁ፣ ነገር ግን ለሌላ ሰው ለመግለጽ ብሞክር ምን እንደሆነ ይጠፋብኛል]] በማለት ካስረዳ በኋላ ጊዜ ምን እንደሆነ ከማወቅ ይልቅ ምን እንዳልሆነ ማወቁ እንደሚቀል አስፋፍቶ መዝግቧል። [11]

የጥንቶቹ ግሪክ ፈላስፎች ጊዜ ማለቂያ የለለው፣ ወደሁዋላም ሆነ ወደፊት የትየለሌ ነው ብለው ሲያስቀምጡ፣ የመካከለኛው ዘመን አውሮጳውያን ደግሞ ጊዜ መነሻም ሆነ መድረሻ ያለው አላቂ ነገር ነው በማለት አስረግጠው አልፈዋል። ኒውተን በበኩሉ በሁሉ ቦት አንድ አይሆነ ቋሚ ጊዜ እንዳለና መሬት ላይ ያለው ጊዜ ከዋክብት ላይ ካለው ጊዜ ጋር እኩል የሚጎርፍ ነው በማለት አስረድቷል። በአንጻሩ ሌብኒትዝ ጊዜ ማለት አንድ አይነትና ቋሚ ሳይሆን አንጻራዊ እንደሆነ አስቀምጧል። [12] ካንት ባንጻሩ ጊዜን ሲተንትን "ጊዜ ማለት ከልምድ ውጭ ገና ስንወለድ አብሮን የሚወለድ ቀደምት እውቀት ሲሆን የገሃዱን አለም እንድንረዳ የሚረዳን አዕምሮአችን የሚያፈልቀው መዋቀር" ነው ብሎታል።.[13] በርግሰን የተባለው ፈላስፋ ደግሞ ጊዜ ማለት ቁስ አካልም ሆነ የአእምሮአችን ፈጠራ አይደለም በማለት ሁለቱንም ክዷል። ይልቁኑ ጊዜ ማለት ቆይታ ማለት ሲሆን፣ ቆይታ በራሱ ደግሞ የውኑ አለም አስፈላጊ ክፍል ሲሆን ከ ፈጠራና ትዝታ ይመነጫል ብሏል።[14]

ከክርስቶስ ልደት በፊት የነበረው ግሪካዊ ፈላስፋ አንቲፎን እንደጻፈው "ጊዜ እውን ሳይሆን በርግጥም ጽንሰ ሃሳብ ወይም ልኬት" ነው ብሎታል። ፓራመንዴስ የተባለው ግሪካዊም ጊዜ፣ እንቅስቃሴና፣ ለውጥ በሙሉ የውሽት ራዕይ እንጂ በርግጥ በግሃዱ አለም ያሉ አይደሉም ብሏል።[15] በቡዲሂስቶችም ዘንድ ጊዜ የውሸት ራዕይ ነው የሚለው አስተሳሰብ እስካሁን ይሰራበታል። ,[16]

በተፈጥሮ ህግጋት አጥኝወች ዘንድ ግን ጊዜ እውን እንደሆነ ይታመናል። በርግጥ አንድ አንድ የፊዚክስ አጥኝወች ኳንትም ሜካኒክስ በይበልጥ እንዲሰራ እኩልዮሹ ያለጊዜ መቀመጥ አለባቸው ይላሉ። ይህ ግን ያብዛናው ሳይንቲስቶች አስተያየት አይደለም።.[17]

አልበርት አንስታይን የጊዜን ትርጉም እስከለወጠበት ዘመን ድረስ የጊዜ ትርጓሜ ኢሳቅ ኒውተን ባስቀመጠው መልኩ ይሰራበት ነበር። ይህም ኒውተናዊ ሲባል ጊዜ ሁሉ ቦታ ቋሚ የሆነ፣ ምንጊዜም የማይቀየርና በሁሉ ቦታና ዘመን እኩል የሚፈስ (ለምሳሌ በከዋክብትና በመሬት ያለው ጊዜ በአንድ አይነት መንገድ ይሚፈስ/የሚለወጥ) ነው የሚል ነው።.[18] በክላሲካል ሳይንስ የሚሰራበት ጊዜ ኒውተናዊ ነው።

በ19ኛው ክፍለዘመን፣ የተፈጥሮ ህግን የሚያጠኑ ሰወች በነኒውተን ይሰራበት የነበረው የጊዜ ትርጓሜ የኮረንቲንና ማግኔት ን ጸባይ ለማጥናት እንደማይመች/እንደማይሰራ ተገነዘቡ። አንስታይን ሳይንቲስቶቹ የገቡበትን ችግር በማስተዋል በ1905 መፍትሄ አቀረበ። ይህም መፍትሄ የብርሃን ፍጥነትን ቋሚነት የተንተራሰ ነበር። አንስታይን እንደበየነው (postulation) በጠፈር ውስጥ የብርሃን ፍጥነት ባማናቸውም ተመልካቾች (ቋሚም ሆነ ተንቀሳቃሽ) ዘንድ አንድ ነው፣ በዚህ ምክንያት በተንቀሳቃሽ ሳጥን ውስጥ የሚፈጠጥ ኩነት የሚወስደው የጊዜ ቆይታ ከሳጥኑ ውስጥ ላለ ተመልካችና ከሳጥኑ ውስጥ ላለ ተመልካች አንድ አይደለም ብሏል። ለምሳሌ እሚንቀሳቀሰው ሳጥን ውስጥ ለ5 ደቂቃ ያክል ቦምብ ቢፈነዳ (ኩነት) ፣ የማይንቀሳቀሰው ከውጭ ያለ ተመልካች ቦምቡ ለ5.5 ደቂቃ እንደፈነዳ ሊያስተውል ይችላል። ሌላ ታዋቂ ምሳሌ ብንወስድ፣ ሁለት መንትያ እህትማማቾች ቢኖሩና አንዱዋ በመንኮራኩር ከመሬት ተነስጣ በብርሃን ፍጥነት በሚጠጋ ፍጥነት ጠፈርን አሥሳ ከስልሳ አመት በኋላ ብትመለስ፣ መንትያዋን አርጅታ ስታገኛት፣ ተመላሿ ግን ገና ወጣት ናት። የዚህ ምክንያቱ፣ አንስታይ እንዳስረዳ፣ የተንቀሳቃሽ ነገሮች ሰዓት ዝግ ብሎ ሲሄድ የማይንቀሳቀሱ ግን ቶሎ ስለሚሄድ ነው።

ባጠቃላይ፣ የሚንቀሳቀሱ ተመልካቾች ከማይንቀሳቀሱ ተመልካቾች ጋር የተለያየ ጊዜ ለአንድ አይነት ኩነት ይለካሉ።

መቼት የሚለው ቃል ከ"መቼ" እና "የት" ቃላቶች የመጣ ሲሆን የጊዜና ኅዋን ጥምረት ያሳያል። ከድሮ ጀመሮ፣ ሰወቸ ጊዜንና ህዋን በማዛመድ ተመልከተዋቸዋል። በተለክ ከ አንስታይን የልዩ አንጻራዊነት እና አጠቃላይ አንጻራዊነት ርዕዮተ አለሞች ወዲህ የጊዜና ኅዋ ጥምረት (መቼት) ለሳይንስ እንደመሰረታዊ ነገር ያገለግላል። በርዕዮቶቹ መሰረት፣ መቼት፣ በእንቅስቃሴ ምክንያት ከአንድ ተመልካች ወደሌላ ተመልካች የሚለያይ እንጂ በአንድ ዋጋ ለሁሉ ተመልካች አይጸናም። በርዕዮቶቹ መሰረት፣ ያለፈው ጊዜ የሚባለው ብርሃን ለአንድ ተመልካች መላክ የሚችሉ ኩነቶች (ክስተቶች) ስብስብ ሲሆን ፣ መጪው ጊዜ ደግሞ አንድ ተመልካች ብርሃን ሊልክባቸው ይሚችላቸው ኩነቶች ስብስብ ነው።

አንስታይን በምናባዊ ሙከራው እንዳሳየ፣ በተለያየ ፍጥነት የሚጓዙ ሰወች በሚያዩዋቸው ኩነቶች (ክስተቶች) መካከል ያለው የጊዜ ልዩነት በሁሉም ተመልካቾች አንድ አይነት ሳይሆን የተለያየ ነው። ማልተ ሁለት ቦምቦች ቢፈነዱና አንዱ ተመልካች 5 ሰከንድ በሁለት ቦምቦች ፍንዳታ መካከል ቢለካ፣ ሌላኛው ደግሞ 6 ሰኮንድ ሊለካ ይችላል (እንደ ፍጥነቱ ይወሰናል)። በተረፈ የቦምቦቹ ፍንዳታ በአማካኝነት (causality) ካልተያያዙ (ማለት ያንዱ ቦምብ ፍንዳታ ለሌላው ቦምብ መፈንዳት ምክንያት ካልሆነ/መንስዔ ካልሆነ)፣ የኩነቶቹ ድርድር ሁሉ ሊለወጥ ይችላል። አንዱ ተመልካች ቀዩ ቦምብ መጀሪያ ከዚያ አረንጓዴው ሲፈንዳ ካየ ሌላው ደግሞ አረንጓዴ መጀመሪያ ከዚያ ቀዩ ሲፈንዳ ሊያስተውል ይችላላ (መረሳት የሌለበት፣ ይህ ሁሉ የሚሆነው ሰወች በብርሃን ፍጥነት አካባቢ እሚጓዙ ከሆነ ብቻ ነው)።

እንደ አንስታይን አገላለጽ፣ ሁለት ኩነቶች በ ነጥብ A እና B ቢፈጠሩ እና ነጥቦቹ በ K ስርዓት ውስጥ ታቃፊ ቢሆኑ፣ ሁለቱ ኩነቶች ባንዴ ናቸው (ባንድ ላይ ተከስቱ) የምንለው ከመሃላቸው ባለው ነጥብ M ላይ ያለ ተመልካች ሁለቱም ኩነቶች ባንድ ቅጽበት ሲከስቱ ሲያይ ብቻ ነው። ስለዚህ ጊዜ ማለት ከስርዓት K አንጻር ባንዴ የሚፈጠሩ ክስተቶችን ባንዴ እንደተፈጠሩ የሚያሳዩና በሥርዓቱ ውስጥ የማይነቀሳቀሱ ሰዓቶች ስብስብ ነው።

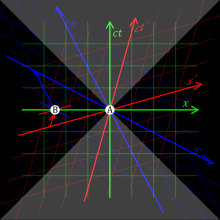

ሥዕሉ የሚያሳየው በአንጻራዊ እና በኒውተናዊ ጊዜ መካከል ያለውን ልዩነት ነው። ይህ ልዩነትም የሚነሳው በጋሊልዩ ለውጥ እና በሎሬንዝ ለውጥ መካከል ባለ አለመጣጣም ነው። የጋሊሊዩ ለኒውተን ሲሰራ የሎሬንዝ ለአንስታይን ይሰራል። ከላይ ወደታች የተሰመረው መሰመር ጊዜን ይወክላል። አድማሳዊው ወይም አግድሙ መስመር ደግሞ ርቀትን ይወካልል (አንድ የኅዋ ቅጥ መሆኑ ነው)። ወፍራም የተቆራረጠው ጠማማ መስመር ደግሞ የተመልካችን መቼት ይወካልል፣ ይህ መስመር የዓለም መስመር ይባላል። ትናንሾቹ ነጠብጣቦች ደግሞ አላፊንና መጪን መቼታዊ ኩነቶች ይወክላሉ።

የዓለም መሰመር ኩርባ ደግሞ የተመልካችን አንፃራዊ ፍጥነት ይሰጣል። በሁለቱም ሥዕሎች እንደምናየው ተመልካቹ ፍጥንጥን ባለ ጊዜ የመቼቱ እይታው ይቀየራል። በኒውተናዊ ትንታኔ እነዚህ ለውጦች የጊዜን ቋሚነት አይቀየሩም ስለዚህም የተመልካቹ እንቅስቃሴ ኩነቱ አሁን መፈጠሩን ወይም አለመፈጠሩን አይለውጠውም (በስዕሉ መሰረት፣ ክስተቱ በአግድሙ መስመር ማለፉን ወይም አለማለፉን )።

በአንጻራዊ ጊዜ ትንታኔ መሰረት ግን፡ "ክስተቶችን የምንመለከትበት ጊዜ ቋሚ የማይናወጥ ሆኖ ስላ፡ ማለተ የተመልካቹ እንቅስቃሴ የተመልካቹን የብርሃን አሹሪት ማለፉን ወይም አለምፉን አይለውጥም። ነገር ግን ከኒውተናዊ (ፅኑ ትንተና) ወደ አንጻራዊ ትንተና በተሻገርን ወቅት ፣ የ"ጽኑ ጊዜ" ጽንሰ ሃሳብ አይሰራም፣ በዚህ ምክንያት ሥዕሉ ላይ እንደምናየው ክስተቶች/ኩነቶች ወደ ላይና ወደታች ከጊዜ አንጻር ይሄዳሉ፣ ይህን የሚወስነው እንግዲህ የተመልካቹ ፍጥንጥነት ነው።

ከለተ ተለት ኑሮ እንደምንረዳው ጊዜ አቅጣጫ ያለው ይመስላል፦ ያለፈው ጊዜ ተመለሶ ላይመጣ ወደ ኋላ ይቀራል፣ የወደፊቱ ደግሞ ከፊትለፊት እየገሰገሰ ይመጣል። በዚህ ምክንያት የጊዜ ቀስት ካለፈው ወደ ወደፊቱ ያለማመንታት ይገሰግሳል። ሆኖም ግን አብዛኛወቹ የተፈጥሮ ህግጋት ጥናት (ፊዚክስ) ህጎች የጊዜን አንድ አቅጣጫ መከተል ዕውቅና አይሰጡም። ለዚህ ተጻራሪ የሆኑ አንድ አንድ ህግጋት በርግጥ አሉ። ለምሳሌ ሁለተኛው የሙቀት እንስቃሴ ህግ እንደሚለው የነገሮች ኢንትሮፒ ከጊዜ ወደጊዜ እየጨመረ እንጂ እየቀነሰ አይሄድም የሚለው ይገኝበታል። የስነ ጠፈር ምርምርም በዚህ አንጻር የጠፈር ጊዜ ከመጀመሪያው ታላቁ ፍንዳታ እንደሚሸሽ ሲያስቀምጥ፣ የስነ-ብርሃን ትምህርት ደግሞ የብርሃን ጨረራዊ ሰዓት በአንድ አቅጣጫ እንደሚተምም ያስቀምጣል። ማንኛውም የመለካት ስርዓት በኳንተም ጥናት፣ ጊዜ አቅጣጫ እንዳለው ያሳያል።

የጊዜ ጠጣርነት ምናባቂ ጽንሰ ሃሳብ ነው። በዘመናዊ ፊዚክስና በ አጠቃላይ አንጻራዊነት ትምህርት ጊዜ ጠጣር አይደለም።

የፕላንክ ጊዜ ተብሎ የሚታወቀው (~ 5.4 × 10−44 ሰከንድ ሲሆን፣ ባሁኑ ጊዜ ያሉት ማናቸውም የተፈጥሮ ህግ ርዕዮተ አለሞች ከዚህ ጊዜ ባነሰ የጊዜ መጠን እንደማይሰሩ ይታመናል (ልክ የኒውተን ህጎች ወደብርሃን ፍጥነት በተጠጋ ስርዓት ውስጥ እንደማይሰሩ)። የፕላንክ ጊዜ ምናልባትም ሊለካ የሚችል የመጨረሻ ታናቹ የጊዜ መጠን ነው፣ በመርህ ደርጃ እንኳ ከዚህ በታች ሰዓት ላይለካ እንዲችል ባሁኑ ጊዜ ይታመናል። በዚህ ምክንያት የጊዜ ጠጣሮቹ መስፈርቶች የ(~ 5.4 × 10−44 ሰከንድ ቆይታ አላቸው ማለት ነው።

- ^ Rynasiewicz, Robert : Johns Hopkins University (2004-08-12). "Newton's Views on Space, Time, and Motion". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. በ2008-01-10 የተወሰደ. “Newton did not regard space and time as genuine substances (as are, paradigmatically, bodies and minds), but rather as real entities with their own manner of existence as necessitated by God's existence... To paraphrase: Absolute, true, and mathematical time, from its own nature, passes equably without relation the [sic~to] anything external, and thus without reference to any change or way of measuring of time (e.g., the hour, day, month, or year).”

- ^ Markosian, Ned. "Time". In Edward N. Zalta. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2002 Edition). Retrieved 2008-JAN-18. "The opposing view, normally referred to either as “Platonism with Respect to Time” or as “Absolutism with Respect to Time,” has been defended by Plato, Newton, and others. On this view, time is like an empty container into which events may be placed; but it is a container that exists independently of whether or not anything is placed in it."

- ^ Burnham, Douglas : Staffordshire University (2006). "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) Metaphysics - 7. Space, Time, and Indiscernibles". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. በ2008-01-10 የተወሰደ. “First of all, Leibniz finds the idea that space and time might be substances or substance-like absurd (see, for example, "Correspondence with Clarke," Leibniz's Fourth Paper, §8ff). In short, an empty space would be a substance with no properties; it will be a substance that even God cannot modify or destroy.... That is, space and time are internal or intrinsic features of the complete concepts of things, not extrinsic.... Leibniz's view has two major implications. First, there is no absolute location in either space or time; location is always the situation of an object or event relative to other objects and events. Second, space and time are not in themselves real (that is, not substances). Space and time are, rather, ideal. Space and time are just metaphysically illegitimate ways of perceiving certain virtual relations between substances. They are phenomena or, strictly speaking, illusions (although they are illusions that are well-founded upon the internal properties of substances).... It is sometimes convenient to think of space and time as something "out there," over and above the entities and their relations to each other, but this convenience must not be confused with reality. Space is nothing but the order of co-existent objects; time nothing but the order of successive events. This is usually called a relational theory of space and time.”

- ^ Mattey, G. J. : UC Davis (1997-01-22). "Critique of Pure Reason, Lecture notes: Philosophy 175 UC Davis". Archived from the original on 2005-03-14. በ2008-01-10 የተወሰደ. “What is correct in the Leibnizian view was its anti-metaphysical stance. Space and time do not exist in and of themselves, but in some sense are the product of the way we represent things. The are ideal, though not in the sense in which Leibniz thought they are ideal (figments of the imagination). The ideality of space is its mind-dependence: it is only a condition of sensibility.... Kant concluded "absolute space is not an object of outer sensation; it is rather a fundamental concept which first of all makes possible all such outer sensation."...Much of the argumentation pertaining to space is applicable, mutatis mutandis, to time, so I will not rehearse the arguments. As space is the form of outer intuition, so time is the form of inner intuition.... Kant claimed that time is real, it is "the real form of inner intuition."”

- ^ McCormick, Matt : California State University, Sacramento (2006). "Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) Metaphysics : 4. Kant's Transcendental Idealism". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. በ2008-01-10 የተወሰደ. “Time, Kant argues, is also necessary as a form or condition of our intuitions of objects. The idea of time itself cannot be gathered from experience because succession and simultaneity of objects, the phenomena that would indicate the passage of time, would be impossible to represent if we did not already possess the capacity to represent objects in time.... Another way to put the point is to say that the fact that the mind of the knower makes the a priori contribution does not mean that space and time or the categories are mere figments of the imagination. Kant is an empirical realist about the world we experience; we can know objects as they appear to us. He gives a robust defense of science and the study of the natural world from his argument about the mind's role in making nature. All discursive, rational beings must conceive of the physical world as spatially and temporally unified, he argues.”

- ^ Cummings, Raymond King (1922). The Girl in the Golden Atom. U of Nebraska Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780803264571. http://books.google.com/?id=tA647bGiWwsC&pg=PA46&lpg=PA46&dq=%22keeps+everything%22#v=onepage&q=%22keeps%20everything%22 በ2010-06-03 የተቃኘ. Chapter 5. Cummings repeated this sentence in several of his novellas. Numerous sources, such as this one, attribute it to his even earlier work, The Time Professor, in 1921. Its appearance in that book has not yet been verified. Before taking book form, several of Cummings's stories appeared serialized in magazines. The first eight chapters of his The Girl in the Golden Atom appeared in All-Story Magazine on March 15, 1919.

- ^ International, Rotary (Aug 1973). The Rotarian. Published by Rotary International. p. 47. ISSN 0035-838X. http://books.google.com/?id=vjUEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PP1., What does a man possess? page 47

- ^ Daintith, John (2008). Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists (third ed.). CRC Press. p. 796. ISBN 1-420-07271-4. http://books.google.com/?id=vqTNfnKJVPAC., Page 796, quoting Wheeler from the American Journal of Physics, 1978

- ^ Davies, Davies (1995). About time: Einstein's unfinished revolution. Simon & Schuster. p. 236. ISBN 0-671-79964-9. http://books.google.com/?id=SZPuAAAAMAAJ.

- ^ Richards, E. G. (1998). Mapping Time: The Calendar and its History. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–5.

- ^ St. Augustine, Confessions, Book 11. Upenn.edu Archived ሜይ 24, 2009 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed 26 May 2007).

- ^ Gottfried Martin, Kant's Metaphysics and Theory of Science

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1787). The Critique of Pure Reason, 2nd edition. http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/k/kant/immanuel/k16p/k16p15.html. Archived ኦክቶበር 7, 2008 at the Wayback Machine "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2008-10-07. በ2010-07-01 የተወሰደ. translated by J. M. D. Meiklejohn, eBooks@Adelaide, 2004

- ^ Bergson, Henri (1907) Creative Evolution. trans. by Arthur Mitchell. Mineola: Dover, 1998.

- ^ Harry Foundalis. "You are about to disappear". በ2007-04-27 የተወሰደ.

- ^ Huston, Tom. "Buddhism and the illusion of time". Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. በ2009-08-19 የተወሰደ.

- ^ "Time is an illusion?". በ2007-04-27 የተወሰደ.

- ^ Herman M. Schwartz, Introduction to Special Relativity, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1968, hardcover 442 pages, see ISBN 0-88275-478-5 (1977 edition), pp. 10-13