Сәфәүиҙәр дәүләте

| Сәфәүиҙәр дәүләте | |||||

| |||||

| Баш ҡала | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Телдәр | |||||

| Рәсми тел |

- | ||||

| Дин | |||||

| Аҡса берәмеге | |||||

| Майҙаны |

3,5 миллион км² (шаһ Ғәббәс хакимлыҡ иткән осорҙа) | ||||

| Халҡы |

20 миллионға тиклем кеше | ||||

| Идара итеү формаһы | |||||

| Династия | |||||

| Закон сығарыу власы | |||||

| Дәүләт башлыҡтары | |||||

Шаханшах | |||||

| • 1501—1524 | |||||

| • 1732—1736 | |||||

| • 1501—? | |||||

| • 1729—1736 | |||||

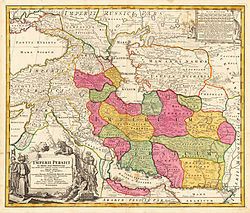

Сәфәүиҙәр дәүләте йәки Сәфәүиҙәр Ираны[15][16], шулай уҡ Сәфәүиҙәр Фарсыһы[17], ҡайһы берҙә Сәфәүиҙәр империяһы (әзерб. Səfəvilər dövləti; фарс. دولت صفویه; Dowlat-e Safaviyye) — Сәфәүиҙәр хакимлыҡ иткән династия исеме менән аталған, орден шәйехе Сәфәүиә Исмәғил I етәкселегендә барлыҡҡа килтерелгән ҡыҙылбаш ҡәбилә конфедерацияһы, 1501-1722 йылдарҙа йәшәгән феодаль дәүләт[18][19][20][21]. Дәүләт территорияһы хәҙерге Әзербайжан, Иран, Әрмәнстан, Грузия, Төркмәнстан, Афғанстан, Ираҡ, көнсығыш Төркиә, Кувейт, Бахрейн территорияларын, шулай уҡ Пакистандың бер өлөшөн, Үзбәкстан менән Тажикстандың көньяғын, Сүриәнен көнсығышын һәм Рәсәйҙең (Дәрбәнт) көньяғын үҙ эсенә алған. Урта быуат сығанаҡтарында дәүләт йыш ҡына Ҡыҙылбаш дәүләте (фарсы. Доулет-е Кызылбаш)[22][23][24] тип аталған.

Юғарыла әйтелгәнсә, Сәфәүиҙәр династияһы Ардебиль ҡалаһында нигеҙләнгән Сәфәүи орденының суфыйҙар нәҫеленән башлана[25]. Был курд сығышлы ҙур иран династияһы булған[26][27][28], улар йыш осраҡта төрки төркмәндәре[29], грузиндар[30], черкестар[31][32] һәм понтий гректары сановниктары менән никахҡа ингән[33], улар И рандың төрки телле халҡы йәки төркиләшкән булған[34]. Үҙҙәренең Ардебилдағы аҫаба еренән Сәфәүиҙәр Оло Иран өлкәләренә контроль булдыра һәм, шул рәүешле, төбәктең Иранға оҡшашлығын[34] һәм Буидтар осоронан башланған Иран милли дәүләтенә рәсми нигеҙ һалғанлығын раҫлай[35].

Сәфәүиҙәр XIII һәм XIV быуаттарҙа Ардебилдә Сәфәүиҙәр тәриҡәтенә нигеҙ һалған Сәфи әд-Дин тоҡомонан булған, ләкин, батшаларын шаһиншаһ тип йөрөтһәләр ҙә, уларҙы Сәсәниҙәр дәүләте дауамы тип булмай[36][37]. Скорее наоборот, тюрки все также были в господствующем положении[38]. Сәфи әд-Диндең тоҡомо Шәйех Жунейд, үҙе тирәләй ҡыҙылбаш атамаһы менән билдәле күп кенә төрки төркмәндәрҙе туплап, тыныс рухи эшмәкәрлектән баш тарта һәм орденды хәрбиләштерә. Башланғанда сөнниҙәр, синкретик һәм ортодоксаль шиғый исламын ҡабул итеп, төрки адептар йоғонтоһонда үҙгәрә![]() . XV һәм XVI быуаттар сигендә шәйех Жунейд Исмаил үҙе яғындағы ҡыҙылбаштар ярҙамында дәүләт дине сифатында шиғыйлыҡ булған ҙур империя төҙөй алған

. XV һәм XVI быуаттар сигендә шәйех Жунейд Исмаил үҙе яғындағы ҡыҙылбаштар ярҙамында дәүләт дине сифатында шиғыйлыҡ булған ҙур империя төҙөй алған![]() .

.

Исмаилдың яулауҙар, үҙ сиратында, әсәһе яғынан Аҡ Ҡуйлылар династияһына яҡын булғанлыҡтан, Аҡ Ҡуйлылар территорияһына дәғүәләре, шулай уҡ Сәфәүиҙәр проектында ышаныс тапҡан бик күп төрки күсмә халыҡтарҙы дәүләттең көсәйә барған үҙәкләштереүе менән шөғөлләнгән Ғосман империяһына ҡаршы тороу динамикаһы менән дан тота.

Сәфәүиҙәр хәҙерге Иран дәүләте өсөн географик нигеҙ булдырыу менән бәйле, улар булдырған дәүләт ҡайһы берҙә Иран милли дәүләтселеген тергеҙеү йәки булдырыу тип ҡабул ителә, әммә бындай ҡараш йыш ҡына дәүләт булдырыуҙа һәм уның эшмәкәрлегендә төрки элементты иғтибарһыҙ ҡалдырыу өсөн тәнҡитләнә![]() .

.

Дәүләттең атамаһы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Станет победителем сердара и шахиншаха гази, Не оставит Кызылбашскому шаху ни Тебриз, ни Шираз.

Muzaffer ola serdarın eya şahenşeh-i qazi, Ne Tebrizi koya Şah-i Kızılbaşa ne Şirazı[39]

.

Яңы ойошторолған дәүләттең рәсми ҡабул ителгән исеме — «Сәфәүиҙәр дәүләте» — әзерб. Səfəvilər Dövləti йәки фарс. دولت صفویه (Доула́т-е Сафавийе́)[40][41]. Теге йәки был тарихи, тарихнамә, географик, традицион, этник сәбәптәр арҡаһында, тарихи һәм заманса сығанаҡтарҙа Сәфәүиҙәр дәүләте атамаһының төрлө варианттарын осратырға мөмкин. Урта быуаттарҙағы сығанаҡтарҙа һәм XVI—XVII быуат рус документтарында[42] дәүләт йышыраҡ «Ҡыҙылбаш дәүләте»[43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50] йәки «Кызылбашия» тип аталған[51] — «Девлет-и Кызылбаш»[52], ә Сәфәүиҙәр власы таралған территориялар — «Үлкә-и Ҡыҙылбаш»[52] йәки «Мәмләкәт-и Ҡыҙылбаш»[24], ә хакимы «Падишаһ-е Ҡыҙылбаш» тип аталған[53]. Шулай уҡ XVI быуат сығанаҡтарында «Төркмән дәүләте» исемен осратырға мөмкин булған[54].

Тарих башы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Династияның килеп сығышы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Сәфәүиҙәрҙең сығышы тураһында аныҡ ҡына мәғлүмәт юҡ. Британия шәрҡиәтсеһе Эдмунд Босуорт билдәләүенсә, Сәфәүиҙәр төрки телендә һөйләшһә лә, сығыштары буйынса улар, моғайын, курд булғандыр[55]. Ибн Баззаз тарафынан 1358 йылда «Савфат әз-сафа» китабында Сәфәүиҙәр генеалогияһында тап шулай күрһәтелгән, уға ярашлы, Сәфәүиҙәр нәҫеле Фирүз Шаһ Зарин Колах исемле курдтан башланған[56][57]. Сәфәүиҙәр тураһында монография һәм "Ислам энциклопедияһы"нда[58] «Сәфәүиҙәр» тигән мәҡәлә яҙған Роджер Сейвори әйтеүенсә, «бөгөн ғалимдар араһында V—XI быуаттарҙа уҡ Ардебиль ҡалаһында төпләнгәндер, моғайын, тигән фараз бар, сөнки Сәфәүиҙәрҙең Иран Курдистанынан булыуы тураһында консенсус бар»[59]. Ләкин икенсе версиялар ҙа бар:

- Исмәғил I батшалыҡ иткәндә, Сәфәүиҙәрҙең «рәсми» генеалогияһы өҫтәмә легендар мәғлүмәткә — нәҫеленең етенсе шиғый имамы Муса әл-Ҡазимдан, ә уның аша беренсе шиғый имамы Али ибн Әбү Талиб затынан килеүен иҫбатларға тейеш була. Петрушевский әйтеүенсә, был хәл алдараҡ, XIV быуатта, булған[60].

- Вальтер Һинц фаразлауынса, Сәфәүиҙәр Йемен ғәрәп сығышлы булған[61].

- Немец шәрҡиәтсеһе Һанс Ромер Исмаил I бер ниндәй икеләнеүһеҙ төрки сығышлы тип иҫәпләй[62]. Луи Люсьен Беллан әйтеүенсә, шаһ Исмәғил I Ардебиль төрөгө[63]. Сәфәүиҙәрҙең килеп сығышын профилле мәҡәләлә ҡараған Мөхәмәт Исмәғил (Кристоф) Марцинковский сефевидтарҙың төрки сығышлы булыуы ихтимал тип иҫәпләй

[64]. "Ираника"ла «Иран халҡы» тигән мәҡәлә авторы Ричард Фрай яҙыуынса, Сәфәүиҙәр нәҫеленә әзербайжан төркиҙәре нигеҙ һалған тип яҙған[65]. Уилер Такстон да Сәфәүиҙәрҙе төрки тип иҫәпләй[66]. Иранский автор Хафез Фармаян, пишет о тюркском происхождении Сефевидов, отмечая их значительную роль в тюркизации северо-западного Ирана[67]. Иран авторы Хафез Фармаян, Сәфәүиҙәрҙең төрки сығышы тураһында яҙып, уларҙың төньяҡ-көнбайыш Иран төркиләшеүендә әһәмиәтле роль уйнауын билдәләне. Ларс Йохансон билдәләүенсә, сәфәүиҙәр теле буйынса төрки династиянан булған[68]. Америка шәрҡиәтсеһе Бернард Льюисҡа ярашлы, Сәфәүиҙәр төрки сығышлы булған һәм Анатолияның (Кесе Азия) төрки халҡына (туркомандар) таянған[69] Девид Аялон яҙғанса, Сәфәүиҙәр сығыштары буйынса фарсы түгел, ә төркиҙәр булған[70]. Исмәғил I-нең атаһы — Сәфи әд-Дин төрки йәш егете тип аталған[71]. Әзербайжан телендәге поэмаһында Сәфәүиҙәр дәүләтенә нигеҙ һалыусы — Исмәғил I үҙен төрөктәрҙең «уңышҡа иҫәп тоторлоҡ кешеһе», «пиры йәки ставкаһы» тип атаған[72]. Питер Голден билдәләүенсә, Сәфәүиҙәр тажын ҡабул итеү махсус баш кейеме кейеү йолаһына эйә ҡарабахтарҡа хас булған, ә Джон Вудс ғөмүмән, Сәфәүиҙәр идараһы Баяндур идараһының яңы сағылышы булыуын әйткән[73]. Рәсәй төркиәтсеһе һәм шәрҡиәтсеһе Василий Владимирович Бартольд Сәфәүиҙәрҙең төрки сығышлы булыуы хаҡында яҙа[74]. Сәфәүиҙәр империяһы төрки-монгол империяһы тип аталған[75]. Стефан Дейл Сәфәүиҙәрҙе Тимуридтарҙың төрки империяһы менән сағыштырған[76]. Уның әйтеүенсә, Сәфәүиҙәр — Аҡҡойонло вариҫтары[77]. М. С. Иванов Сәфәүиҙәр империяһын төрки империя тип атай[78]. Насруллаһ Фәлсәфи — иран ғалимы, Сәфәүиҙәр империяһына нигеҙ һалыусы — Исмәғил I, «иран сығышлы булыуҙы һәм телен» күрә алмаған тип раҫлай[79]. Бак-Граммонт, Ғосмандарҙың менән Сәфәүиҙәрҙең ҡара-ҡаршы тороуы — ул төрөктәр менән ирандарҙың ҡаршы тороуы түгел, сөнки Сәфәүиҙәр, хатта ғосманлыларға ҡарағанда ла — төркиҙәр, тип раҫлай[80]. Рио Жиль Сәфәүиҙәр нәҫеле — төрки тип раҫлай[81].

- Әхмәд Кәсрәүи, Сәфәүиҙәр төп ирандар булған, ләкин ул саҡтағы Әзербайжан халҡы һөйләшкән әзербайжан төрки телендә һөйләшкән, тигән һығымтаға килгән. Шулай уҡ Сәфәүиҙәр генеалогияһын ентекле өйрәнгән төрөк ғалимы Зәки Вәлиди Туған әйтеүенсә, Сәфәүиҙәр 1025 йылда Ардебилде яулап алыу походында Курд принцы Раввадидтар ырыуы Мамлан ибн Вахсуданды оҙата килгән. Шул уҡ ваҡытта, әзербайжан төрки телендә һөйләшеүенә нигеҙләнеп, Ә. В. Туған Исмәғил I-не төрөк тип иҫәпләй[82].

- Күп ғалимдар, башлыса урта быуат Ираны буйынса белгестәр түгел, Сәфәүиҙәр әзербайжан булған[83], Хью Сетон-Уотсон (Hugh Seton-Watson) да шундай фекерҙә була[84]. Ричард Фрай — «Ираника» энциклопедияһында Сәфәүиҙәр династияһына әзербайжан төркиҙәре нигеҙ һалған, тип яҙа[85].

Династияның теле

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Роджер Сэйвори, сәфәүиҙәр төркиләшкән генә, тип иҫәпләһә лә, улар шулай уҡ туған тел булараҡ, төрөк теленә эйә булған[86], әммә, В. Минорский фекеренсә, улар, туған теле булараҡ, шулай уҡ фарсы телен дә белгән. Күп кенә тарихсылар фекеренсә, тәүге Сәфәүи шәйехтәр Ардебилдә йәшәгән[59][87] һәм уларҙың туған теле төрки теле булған[87]. Династияның ҡайһы бер вәкилдәре төрки телендә һәм фарсы телендә шиғырҙар яҙған[88][89]. Атап әйткәндә, орденға нигеҙ һалыусы Сәфи әд-Дин (1256—1334) әзербайжан иран телендә шиғырҙар ижад иткән [90], орденға нигеҙ һалыусы Сәфи әд-Дин (1256—1334) иран әзери телендә шиғырҙар яҙған — династияға нигеҙ һалыусы һәм дәүләттең беренсе шаһы, Хатаи псевдонимы аҫтында шиғырҙар яҙған Исмәғил I — әзербайжан шиғриәте классигы тип һанала[91]. Ә шаһ Ғәббәс II Тани исеме менән төрки шиғырҙар яҙған.

Сәфәүиҙәр ордены

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]1301 йылда Суфый шәйехе Заһит Ғиләниҙең уҡыусыһы һәм кейәүе Сәфи әд-Дин Исхаҡ ҡайһының васыяты буйынса мөршит булып, тәүгеләрҙән булып Сәфәүиә тәриҡәтенә (орден) нигеҙ һалған[92]. Сәфи әд-Диндән һуң орден менән уның Сәфәүи булараҡ билдәле вариҫтары етәкселек итә. Сәфәүиә ордены ортодоксаль суфыйсылыҡҡа («юғары суфыйсылыҡ») нигеҙләнә һәм Сәфи ад-Диндең текстарын анализлау уның тәғлимәтенең халыҡтың белемле өлөшөнә иҫәпләнеүен күрһәтә. Сәфи әд-Дин шәриғәт ҡанундарынан тайпылмаған изге кеше тип таныла һәм замандаштары (шул иҫәптән монгол хакимдары һәм министрҙары), шулай уҡ ортодоксаль сөнниҙәрҙең киләһе быуындары, хатта Ғосман империяһының хакимдары итеп таныла. Сәфи әд-Дин шәриғәт ҡанундарынан тайпылмаған изге кеше тип таныла һәм замандаштары (шул иҫәптән Хүләкүләр монгол хакимдары һәм министрҙары), шулай уҡ ортодоксаль сөнниҙәрҙең киләһе быуыны, хатта XVI быуатта Сәфәүиҙәрҙең ажар дошманына әйләнгән Ғосман империяһының вельможалары (атаҡлы нәҫелдән сыҡҡан бай түрәләре) тарафынан хөрмәт ителгән [93]. Ардебилдә урынлашҡан ордендың Әзербайжанда, Анатолияла, Ираҡта, Ширванда меңләгән эйәрсендәре булған[94]. 1334—1391 йылдарҙа ордендың мөршиде булған Сәфи әд-Диндең улы Саҙретдин Муса осоронда Сәфәүиәнең йоғонтоһо арта ғына барған, илһанид әмирҙәре һәм аристократтар — орден мөриттәре, ә орден байлыҡтары иҫәпһеҙ-хисапһыҙ булып киткән[95]. Саҙретдин Мусанан һуң Хужа Али (1427 йылда вафат булған) һәм Шәйех Ибраһим (1447 йылда вафат булған) сәфәүи мөршите булған[96]. Ибраһим осоронда ордендың ҡеүәте хатта ата-бабалары осорона ҡарағанда ла ҙурыраҡ булған — сығанаҡтарҙан күренеүенсә, Ардебиль провинцияһында берәү ҙә уға ҡаршы әйтергә баҙнат итмәгән, ә «(уның) аш-һыуы алтын һәм көмөш һауыт-һабаларҙа тәҡдим ителгән ризыҡтар менән тулы булған; уларҙың манералары (үҙен тотоу рәүеше) ысын мәғәнәһендә королдәрҙекенсә булған»[97]. Ғосман солтандары йыл һайын «çerağ akçesi» тип аталған сәфәүи тәккәһенә йәки ғибәҙәтханаһына (хәнәкә) бүләктәр ебәргән[98]. Шуға ҡарамаҫтан орден тыныс килеш һәм бер ниндәй сәйәси дәғүәһеҙ ҡалған, ә белемле ҡала халҡына йүнәлеш тотҡан[99].

Ордендың сәйәсиләштерелеүе, шиғыйлаштырылыуы һәм милитаризацияланыуы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Шәйех Ибраһим үлгәндән һуң, уның улы Шәйех Жунейд мөршид булып китә, ул ортодоксаль орден башлығының тыныс тормошо менән сикләнергә теләмәй. Жунейдтың ортодоксаль булмаған дини ҡараштары һәм сәйәси амбициялары асыҡ күренеү менән, Ибраһимдың ағаһы Шәйех Жафар мөршидлеккә дәғүә итә башлай. Орден ике төркөмгә бүленгән. Традиционалистар Жафар тирәләй берләшә, шул уҡ ваҡытта Анатолия һәм Сүриә күсмә төрки ҡәбиләләренән сыҡҡан кешеләр ордены башлығы итеп Жунейдты күрергә теләгән. Ҡара Ҡуйлы Жаһаншаһ солтан, Жунейдтың донъя менән идара итергә дәғүәһенә борсолоп, бәхәскә ҡыҫыла һәм Жунейдты һөргөнгә китергә мәжбүр итә[100].

Жунейд Анатолияға юллана, бында ул урындағы төрки күсмә халыҡтары яғынан ярҙамға өмөтләнә[101]. Уларҙың ислам дине күптән түгел ҡабул ителгән һәм етди булмай, уларҙың дини ҡараштары исламға тиклемге дини инаныуҙар менән аралаштырылған «халыҡ» суфыйсылығынан ғибәрәт ине[102].

Фариба Заринбаф-Шахр билдәләүенсә, үҙәкләштерелгән власҡа бик мохтаж Анатолияға төрки (туркоман) ҡәбиләләре бында алып килгән төрлө христиан һәм ислам ағымдары, Урта Азия шаманизмы ҡатнашҡан төрлө ортодоксаль булмаған ағымдарҙы үҫтереү өсөн бик уңайлы нигеҙ, христианлыҡ һәм ислам фронтиры булып торған[103]. Быға Pax Mongolica менән бәйле дини түҙемлеге булышлыҡ иткән[104]. Реинкарнация идеялары, Алланың кеше формаһындағы күренештәре, Мәхдиҙең килеүенә ышаныу, Сухраварди, Ибн Араби философиялары, трансценденталь осоштоң, бейеүҙәрҙең шаманистик тәжрибәләре популяр була[103]. XIV быуатта һөнәрселәр (ахи) ҡәрҙәшлеге төбәктең дини япмаһына Шиғый элементтарын өҫтәгән, ә XV быуатта хуруфизмдың кабалистик идеологияһының көслө йоғонтоһо барлыҡҡа килгән, айырыуса әзербайжан шағиры Нәсимиҙең мистик шиғырҙары аша[105]. Бабак Рәхими Анатолий суфыйлығын (дәрүиш исламы) төрки күсмә халыҡтарҙың дала (инструменталь) дини тәжрибәләрен иран-семит һәм грек-византий йәмғиәттәренең универсаль (сотериологик) диндәре менән аралашыуының үҙенсәлекле сағылышы тип атай[104].

Шәйех Жунейд тирәләй элекке шәйехтәрҙең ҡараштарынан бөтөнләй айырылып торған, суфый, әлид, гулат (радикаль-шиғый) һәм төрки-монгол ҡиммәттәрен берләштергән ҡарашлы Сәфәүиә Орденының фракцияһы барлыҡҡа килгән[106]; унан да бигерәк, Сәфәүиә башҡаса тыныс сәйәси орден булмаған, ә экстремистик мистик хәрәкәткә әйләнгән[99]. Хәҙерге заман тарихсыһы М. М. Маззауи, шуға күрә шәйех Жунейдҡа тиклемге осорға «суфыйҙар ордены», ә артабанғы осорға — «сәфәүиҙәр хәрәкәте» терминын ҡуллана[97]. Сәйәси амбициялы Шәйех Жунейд, шиғыйлыҡҡа ярашлы, Али тоҡомдары ғына мосолман йәмғиәте менән етәкселек итергә хоҡуҡлы булғанлыҡтан, алдап сығышы Алиҙан башланғанлығын күрһәтеп, үҙенең идпара итеүгә дәғүәһен иҫбатлай[107].

Аҡ Ҡуйлылар менән союзы һәм никахлашыуы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Трапезундан һуң Жунейд Аҡ-Ҡуйлы хакимы Оҙон Хәсән һарайына юл тота. Был йорт Ҡара Ҡуйлы Жаһаншаһ менән дошманлашҡан. Тәүҙә Оҙон Хәсән Жунейдҡа шикләнеп ҡараған һәм уны һаҡ аҫтына алған, ләкин һуңынан Жунейд менән союздан буласаҡ файҙаға иғтибар иткән. Жунейдты туркомандар хуплаған. Оҙон Хәсән Жунейдты һеңлеһе Хәтижә бегумға өйләндерә, туғанлашҡан[108]. әфәүи мөриттәре Аҡ Ҡуйлының күп кенә уңышлы походтарында ҡатнашҡан[109].

Жунейд Хәлилуллаға ҡаршы походта еңелә һәм һәләк була[110].

Жунейдтың вариҫы улы Шәйех Гейдар[111]. Гейдар Оҙон Хәсән һарайында үҫә, 1467 йылда, Оҙон Хәсән Әзербайжанды яулағандан һуң, ул Ардебилгә күсә. Шәйех Жафар тәрбиәһендә үҫһә лә, һуңынан уның менән тынышмай, уны хәнәкәнән (ложа) ҡыуа[112].

Оҙон Хәсән, Сәфәүиҙәр менән созын нығытыу маҡсатында, Гейдарға ҡыҙын бирә. Сәфәүи һарай яны тарихсылары династияның икеләтә: Сәфәүиҙәр орденының рухи власы һәм Аҡ Ҡуйлылар династияһының донъяуи власы аша легитимлы булыуы тураһында яҙғандар[113].

[[Файл:Sheikh-safi.jpg|thumb|Сәфи әд-Дин кәшәнәһе [[Файл:1541-Battle in the war between Shah Isma'il and the King of Shirvan-Shahnama-i-Isma'il.jpg|left|thumb|170px|Шаһ Исмәғил һәм ширваншаһ Фәррух Ясар араһында алыш]]

Тарихы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]

Көнсығыш сиктәре сәйәсәте

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]

Ғосман империяһы менән ҡара-ҡаршы тороуы. Чалдыран алышы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]

Шаһ Тахмасп I. Дәүләттпең эске хәле.

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]

Шаһ Бөйөк Ғәббәс I. Державаның яңырыуы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]

Феодал анархияға ҡаршы көрәш

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Реформалар

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Аҡса реформаһы илдең иҡтисади хәлен тотороҡландыра. Европа илдәре менән сауҙа килешеүҙәре төҙөлә. Илдә Англия, Голландия һәм Франция менән сауҙа факториялары булдырыла, тышҡы сауҙа йәнләнә. Тышҡы сәйәси бәйләнештәр булдырыла, Европа хакимдарына илселәр ебәрелә. Баш ҡала Казвиндан сиктән алыҫыраҡ урынлашҡан Исфаханға күсерелә.

Үзбәктәрҙе тар-мар итеү. Ғосман империяһын еңеү һуғыштары

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Эске сәйәсәт

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Тышҡы сәйәсәт

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Административ-сәйәси ҡоролошо

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Хөкүмәте һәм хакимиәте

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Административ-территориаль бүленеше

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]

Суд системаһы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Халҡы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Солтан Хөсәйен

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Сәфәүи дәүләтенең ҡолауы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Сәфәүиҙәр хакимлығы осоронда мәҙәниәт

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]XVI—XVII быуат архитектураһы юғары художестволы һәйкәлдәре менән танылған. Ардебилдәге Сәфәүиҙәр мәсете, шулай уҡ Һарун Виләйәт мәсете һәм Исфахандағы Мәсжид-и Али мәсете[114].

XVI — XVII быуаттың беренсе яртыһына миниатюра сәнғәте үҫешә. Герат миниатюра мәктәбенең иң ҙур вәкиле Камалетдин Беһзад була. Мөхәммәт Нихами Ғәнжәүи поэмаларын һәм Шаһнамәне миниатюралар менән биҙәй[115].

Иҡтисады

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Аҡса системаһы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]- Монеты, отчеканенные от имени правителей Сефевидского государства в Музее истории Азербайджана (Баку)

-

Шах Исмаил I, серебряный шахи, 1504 год

-

Шах Исмаил I, серебряный шахи, 1506 год

-

Шах Тахмасп I, серебряный шахи, 1567 год

-

Шах Аббас I, серебряная монета, 1587 год

-

Шах Аббас I, серебряная монета, 1587 год

Ауыл хужалығы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Сауҙа юлдары

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]

Теле

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]Сәфәүиҙәр һарайында фарсы телендә һөйләшкәндәр 2016 йыл 4 март архивланған.</ref> 1607 йылда Ғәббәс I, уның ярандары йәғни юғары ҡатлам кешеләре, ғәҙәттә төрөк телендә һөйләшәләр. Төрөк теле ирҙәрсә һәм яугирҙәргә килешә, тигән фекер әйттеләр. Ирандар даими рәүештә: „qorban olim, din imanum padshah, bachunha dunim“ (әзерб. qurban olum, din imanım padşah, başına dönüm)» тип ҡабатлағандар [116][117].

Армияһы

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]-

Шаһ Исмәғил I-нең торҡаһы

-

Сәфәүиә мушкетёры. XVII быуат миниатюраһы

-

Сәфәүиҙәр осоро һуғыш ҡоралы (XVI—XVIII бб.)

-

Сәфәүиҙәр осоро һуғыш ҡоралы (XVI—XVIII бб.)

Сәфәүиҙәр дәүләте хакимдары

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]- 1. Абу-л-Мозаффар Шах Исмаил I, сын Шейха Хайдара, р. 1487, шейх Ардебиля 1497—1502, шах Азербайджана с 1501, шаханшах Ирана 1502—1524

- 2. Абу-л-Фатх Шах Тахмасп I, сын Шаха Исмаила I, р. 1513, шаханшах Ирана 1524—1576

- Див-султан Румлу (регент 1524—1527)

- Чуха-султан Устаджлу (регент 1527—1530)

- Хусейн-хан Шамлу (регент 1530—1533)

- 3. Абу-л-Мозаффар Шах Исмаил II, сын Шаха Тахмаспа I, р. 1537, шаханшах Ирана 1576—1577

- 4. Абу-л-Мозаффар Шах Мохаммад I Ходабенде, сын Шаха Тахмаспа I, р.1531, шаханшах Ирана 1577—1587, ум.1595

- Махд-и-Улийа, жена (de-facto 1578—1579).

- Хамза Мирза, сын (de-facto).

- 5. Абу-л-Мозаффар Шах Аббас I Великий, сын Шаха Мохаммада I, р. 1571, шаханшах Ирана 1587—1629

- Муршид Кули-хан Устаджлу (регент 1587—1588)

- 6. Абу-л-Мозаффар Шах Сефи I, сын шахзадэ солтан Сефи-мирзы, р. 1611, шаханшах Ирана 1629—1642

- 7. Абу-л-Мозаффар Шах Аббас II Сефевид, сын Шаха Сафи I, р. 1632, шаханшах Ирана 1642—1666

- 8. Абу-л-Мозаффар Шах Солейман Сефи (Сефи II), сын Шаха Аббаса II, р. 1647, шаханшах Ирана 1666—1694

- 9. Абу-л-Мозаффар Шах Хосейн I, сын Шаха Сефи II Солеймана, р. 1668, шаханшах Ирана 1694—1722, ум. 17261

1722—1729 афганское завоевание.

- 10. Абу-л-Мозаффар Шах Тахмасп II, р. 1704, сын Шаха Хосейна I, р. 1668, шаханшах Ирана 1724—1732, ум. 1736

- Мир Махмуд (регент 1722—1725, в Кандагаре с 1716)

- 11. Шах Ахмад (шаханшах Ирана), сын Мирзы Абу-л-Касима, шаханшах Ирана 1726—1728, правил в Кермане и Фарсе

- 12. Шах Аббас III, сын Шаха Тахмаспа II, р. 1732, шаханшах Ирана 1732—1736, ум. 1740

- Надир Кули-бек Афшар (регент 1732—1736)

Сәфәүиҙәр шаһтары

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]-

Шаһ Исмаил I

-

Шаһ Тахмасп I

-

Шаһ Исмаил II

-

Шаһ Аббас I

-

Сәфи I

-

Шаһ Аббас II

-

Шаһ Сөләймән I

-

Шаһ Солтан Хөсәйен

Сәфәүиҙәр дәүләте флагтары

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]-

1501-1524 йй. флагы

-

1524-1576 йй. флагы

-

1576-1666 йй. флагы

Иҫкәрмәләр

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]- ↑ Matthee, 2010, p. 234

- ↑ Britannica, Safavid dynasty.

- ↑ 3,0 3,1 John R Perry, "Turkic-Iranian contacts", Encyclopædia Iranica, January 24, 2006: "...written Persian, the language of high literature and civil administration, remained virtually unaffected in status and content"

- ↑ Rudi Matthee, "Safavids Архивная копия от 24 май 2019 на Wayback Machine" in Encyclopædia Iranica, accessed on April 4, 2010. "The Persian focus is also reflected in the fact that theological works also began to be composed in the Persian language and in that Persian verses replaced Arabic on the coins." "The political system that emerged under them had overlapping political and religious boundaries and a core language, Persian, which served as the literary tongue, and even began to replace Arabic as the vehicle for theological discourse".

- ↑ Arnold J. Toynbee, A Study of History, V, pp. 514-15. excerpt: "in the heyday of the Mughal, Safawi, and Ottoman regimes New Persian was being patronized as the language of literae humaniores by the ruling element over the whole of this huge realm, while it was also being employed as the official language of administration in those two-thirds of its realm that lay within the Safawi and the Mughal frontiers"

- ↑ Michel M. Mazzaoui, «Islamic Culture and literature in the early modern period» Архивная копия от 22 апрель 2022 на Wayback Machine in Robert L. Canfield, Turko-Persia in historical perspective, Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 87 Оригинал текст (инг.)

Safavid power with its distinctive Persian-Shi'i culture, however, remained a middle ground between its two mighty Turkish neighbors. The Safavid state, which lasted at least until 1722, was essentially a "Turkish" dynasty, with Azeri Turkish (Azerbaijan being the family's home base) as the language of the rulers and the court as well as the Qizilbash military establishment. Shah Ismail wrote poetry in Turkish and Persian. The administration nevertheless was Persian, and the Persian language was the vehicle of diplomatic correspondence (insha'), of belles-lettres (adab), and of history (tarikh)

- ↑ Willem Floor and Hasan Javadi The Role of Azerbaijani Turkish in Safavid Iran // Iranian Studies. — 2013. — Vol. 46. — № 4. — С. 569—581.

- ↑ Cambridge History of Iran, 1986, p. 951: «So much for one notable regional development. On a larger scale what demands attention is the marked interest the Safavid monarchs themselves took in the Turkish language, in addition to the factor already touched upon, that most of th expression used in the goverment, court andarmy were in that language.»

- ↑ Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective - "the Safavid state, which lasted at least until 1722, was essentially a "Turkish" dynasty, with Azeri Turkish (Azerbaijan being the family's home base) as the language of the rulers and the court as well as the Qizilbash military establishment. Shah Ismail wrote poetry in Turkish. The administration nevertheless was Persian, and the Persian language was the vehicle of diplomatic correspondence (insha'), of belles-lettres (adab), and of history (tarikh)."

- ↑ Mazzaoui, Michel B; Canfield, Robert (2002). "Islamic Culture and Literature in Iran and Central Asia in the early modern period" Архивная копия от 22 апрель 2022 на Wayback Machine. Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 86—87. ISBN 978-0-521-52291-5. "Safavid power with its distinctive Persian-Shi'i culture, however, remained a middle ground between its two mighty Turkish neighbors. The Safavid state, which lasted at least until 1722, was essentially a "Turkish" dynasty, with Azeri Turkish (Azerbaijan being the family's home base) as the language of the rulers and the court as well as the Qizilbash military establishment. Shah Ismail wrote poetry in Turkish. The administration nevertheless was Persian, and the Persian language was the vehicle of diplomatic correspondence (insha'), of belles-lettres (adab), and of history (tarikh)."

- ↑ Zabiollah Safa (1986), "Persian Literature in the Safavid Period", The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-20094-6, pp. 948–65. P. 950: "In day-to-day affairs, the language chiefly used at the Safavid court and by the great military and political officers, as well as the religious dignitaries, was Turkish, not Persian; and the last class of persons wrote their religious works mainly in Arabic. Those who wrote in Persian were either lacking in proper tuition in this tongue, or wrote outside Iran and hence at a distance from centers where Persian was the accepted vernacular, endued with that vitality and susceptibility to skill in its use which a language can have only in places where it truly belongs."

- ↑ Savory, Roger (2007). Iran Under the Safavids. Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-521-04251-2. "qizilbash normally spoke Azari brand of Turkish at court, as did the Safavid shahs themselves; lack of familiarity with the Persian language may have contributed to the decline from the pure classical standards of former times"

- ↑ Price, Massoume (2005). Iran's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-57607-993-5. "The Shah was a native Turkic speaker and wrote poetry in the Azerbaijani language."

- ↑ «Mission to the Lord Sophy of Persia, (1539- 1542) / Michele Membré ; translated with introduction and notes by A.H. Morton», p. 10-11

- ↑ Andrew J. Newman. Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- ↑ Colin P. Mitchell. The Practice of Politics in Safavid Iran: Power, Religion and Rhetoric, I.B. Tauris, 2009.

- ↑ Charles P. Melville. Safavid Persia: The History and Politics of an Islamic Society, I.B. Tauris, 1996.

- ↑ Helen Chapin Metz, ed., Iran, a Country study. 1989. University of Michigan, p. 313.

- ↑ Emory C. Bogle. Islam: Origin and Belief. University of Texas Press. 1989, p. 145.

- ↑ Stanford Jay Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Press. 1977, p. 77.

- ↑ Andrew J. Newman, Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire, IB Tauris (March 30, 2006).

- ↑ Петрушевский, 1949

- ↑ История Ирана, 1958

- ↑ 24,0 24,1 Lucien-Louis Bellan. Chah 'Abbas I Ier: sa vie, son histoire.

- ↑ Rudi Matthee. The Safavid World. — 1. — London: Routledge, 2021-05-27. — ISBN 978-1-003-17082-2.

- ↑ Rudi Matthee The Pursuit of Pleasure. — 2005-12-31. — DOI:10.1515/9781400832606

- ↑ EBN BAZZĀZ. Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. Дата обращения: 8 октябрь 2022.

- ↑ Ṣafavid Dynasty. Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Дата обращения: 8 октябрь 2022.

- ↑ Richard W. Bulliet, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart The Cambridge History of Iran. Volume 6, The Timurid and Safavid Periods // The American Historical Review. — 1988-04. — В. 2. — Т. 93. — С. 470. — ISSN 0002-8762. — DOI:10.2307/1860028

- ↑ Aptin Khanbaghi. The fire, the star and the cross : minority religions in medieval and early modern Iran. — London: I.B. Tauris, 2006. — 1 online resource (xvi, 268 pages) с. — ISBN 1-4237-8776-5, 978-1-4237-8776-1, 1-84511-056-0, 978-1-84511-056-7, 978-0-85771-266-0, 0-85771-266-7.

- ↑ Ehsan YARSHATER A Star Ceases to Shine // Persica. — 2001-01-01. — В. 0. — Т. 17. — С. 137–153. — ISSN 0079-0893. — DOI:10.2143/pers.17.0.505

- ↑ Aptin Khanbaghi. The Fire, the Star and the Cross. — I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2006. — ISBN 978-1-78453-746-3, 978-0-7556-0762-4.

- ↑ Anthony Bryer Greeks and Turkmens: The Pontic Exception // Dumbarton Oaks Papers. — 1975. — Т. 29. — С. 113. — ISSN 0070-7546. — DOI:10.2307/1291371

- ↑ 34,0 34,1 Akihiko Yamaguchi The Kurdish frontier under the Safavids // The Safavid World. — London: Routledge, 2021-05-27. — С. 556–571. — ISBN 978-1-003-17082-2.

- ↑ Edmund Herzig, Sarah Stewart Foreword // Early Islamic Iran. — 2012. — DOI:10.5040/9780755693498.0005

- ↑ Douglas E. Streusand. «Islamic Gunpowder Empires. Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals». — С. 137.

- ↑ «Safavid Persia in the Age of Empires». — С. 19.

- ↑ Гочков О.А. «ОЧЕРКИ ПО ИСТОРИИ ПЕРСИДСКОЙ КАЗАЧЬЕЙ БРИГАДЫ».

- ↑ Metin Akkuş, «Nef’i Divanı»

- ↑ Пигулевская Н. В., Якубовский А. Ю., Петрушевский И. П., Строева Л. В., Беленицкий А. М. История Ирана с древнейших времён до конца XVIII века. — С. 255.

- ↑ Петрушевский И. П. Очерки по истории феодальных отношений в Азербайджане и Армении в XVI — начале XIX вв. — С. 37.

- ↑ Заходер Б. Н. Сефевидское государство 2012 йыл 6 май архивланған.Оригинал текст (инг.)

Прозвище «кызыл-баши» скоро стало синонимом Сефевидов. В русских документах XVI—XVII вв. династия и государство Сефевидов преимущественно именуются кызыл-башами.

- ↑ Петрушевский, 1949, с. 37

- ↑ История Ирана, 1958, с. 254—255

- ↑ Roger Savory. Iran Under the Safavids. Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-521-04251-8, 9780521042512, с. 34 Архивная копия от 16 сентябрь 2018 на Wayback Machine.

- ↑ История Востока. — Восточная Литература, 2000. — Т. III. — С. 100. Основанное Исмаилом I Сефевидом (1502—1524) государство чаще всего и называлось Доулет-е Кызылбаш, то есть Кызылбашское государство.

- ↑ Solaiman M. Fazel. Ethnohistory of the Qizilbash in Kabul: Migration, State, and a Shi’a Minority. — P. 83. Оригинал текст (инг.)

Thus, the Safavid State became synonymous with the expressions: kalamraw-i Qizilbash, Qizilbash Realm, and mamlikat-i Qizilbash, Qizilbash Country. At the same time, the person of Shah was not only the Murshid-e Kamil, but he was now also referred to as the Padishah-e Qizilbash, or the Qizilbash Shah (Munshi 1616, 206).

- ↑ Корганян Н. К., Папазян А. П. Абраам Кретаци, Повествование. — С. 290.Оригинал текст (рус.)

Число этих шиитских племён, говоривших н азербайджанском языке, впоследствии значительно возросло. Сефевиды пришли к власти, опираясь на военную силу кызылбашей, поэтому государство Сефевидов называлось Кызылбашской державой (Доулет-и Кызылбаш).

- ↑ İslâm Ansiklopedisi, KızılbaşОригинал текст (төр.)

Safevî Devleti’nin kurulmasıyla birlikte kızılbaş ismi, devlet bünyesinde kurucu unsuru teşkil etmesi bakımından “Türk yahut Türkmen”, daha sonra mülkî idarede ağırlıklı olarak muharip gücü teşkil etmesi bakımından “askerî aristokrasi” anlamında kullanılmıştır (EI² [İng.], V, 244). Bu çerçevede kızılbaş oymakları “tavâif-i kızılbaş”, emîrler “ümerâ-yi kızılbaş”, ordu “leşker-i kızılbaş”, hükümdar “pâdişah-ı kızılbaş”, devlet ise “ülke-i kızılbaş, devlet-i kızılbaş” adlarıyla anılmıştır (Sümer, s. 150).

- ↑ Кутелия Т. Грузия и Сефевидский Иран (по данным нумизматики).

- ↑ Бушев П. П. История посольств и дипломатических отношений Русского и Иранского государств в 1613—1621 гг.

- ↑ 52,0 52,1 Өҙөмтә хатаһы:

<ref>тамғаһы дөрөҫ түгел;:02төшөрмәләре өсөн текст юҡ - ↑ Haneda M. The Evolution of the Safavi Royal Guard.

- ↑ Yılmaz Öztuna. Yavuz Sultan Selim. — p. 7.Оригинал текст (төр.)

Safevi Devleti'nin XVI. asır metinlerinde geçen adı Türkmen Devleti'dir.

- ↑ Эдмунд Босуорт. «Мусульманские династии» (Перевод с английского и nримечания П. А. Грязневича), страница 226

- ↑ F. Daftary, «Intellectual Traditions in Islam», I.B.Tauris, 2001. pg 147: «But the origins of the family of Shaykh Safi al-Din go back not to Hijaz but to Kurdistan, from where, seven generations before him, Firuz Shah Zarin-kulah had migrated to Adharbayjan»

- ↑ Savory. Ebn Bazzaz. 2017 йыл 17 ноябрь архивланған. // Encyclopædia Iranica: «Shah Ṭahmāsb (930-84/1524-76) ordered Mīr Abu’l-Fatḥ Ḥosaynī to produce a revised edition of the Ṣafwat al-ṣafāʾ. This official version contains textual changes designed to obscure the Kurdish origins of the Safavid family and to vindicate their claim to descent from the Imams.»

- ↑ Roger Savory. Iran Under the Safavids. Cambridge University Press, 2007

- ↑ 59,0 59,1 Encyclopaedia of Islam. SAFAWIDS. «There seems now to be a consensus among scholars that the Safawid family hailed from Persian Kurdistān, and later moved to Azerbaijan, finally settling in the 5th/11th century at Ardabīl»

- ↑ B. Nikitine. Essai d’analyse du afvat al-Safā. Journal asiatique. Paris. 1957, с. 386.

- ↑ Walther Hinz. Irans aufstieg zum nationalstaat im fünfzehnten jahrhundert. Walter de Gruyter & co., 1936

- ↑ Riza Yildirim. «Turkomans between Two Empires:The Origins of the Qizilbash Identity in Anatolia (1447–1514)». — С. 158.

- ↑ Lucien-Louis Bellan. «Chah 'Abbas I Ier: sa vie, son histoire».

- ↑ M. Ismail Marcinkowski. «From Isfahan to Ayutthaya: Contacts Between Iran and Siam in the 17th Century».

- ↑ The Azeri Turks are Shiʿites and were founders of the Safavid dynasty. Дата обращения: 29 май 2014. Архивировано 10 август 2011 года.

- ↑ W.M. Thackston. «The Baburnama». — С. 10.

- ↑ Hafez F. Farmayan. «The Beginning of Modernization in Iran: The Policies and Reforms of Shah Abbas (1587—1629)». — С. 15.

- ↑ L. Johanson. «Isfahan — Moscow — Uppsala. On Some Middle Azeri Manuscripts and the Stations Along Their Journey to Uppsala». — С. 169.

- ↑ Bernard Lewis. «The Middle East: A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years». — С. 113.

- ↑ David Ayalon. Gunpowder and Firearms in the Mamluk Kingdom: A Challenge to a Mediaeval Society. Vallentine, Mitchell, 1956. С. 109.

- ↑ Eskander Beg Monshi. «History of Shah Abbas the Great». — С. 22.

- ↑ В. Минорский. «Поэзия шаха Исмаила I». — 1006а с.

- ↑ Colin Paul Mitchell. «The Sword and the Pen: Diplomacy in Early Safavid Iran, 1501-1555». — С. 178.

- ↑ В.В. Бартольд. «Сочинения». — С. 748.

- ↑ Lisa Balabanlilar. «Lords of the Auspicious Conjuction : Turco-Mongol Imperial Identity on the Subcontinent». — С. 10.

- ↑ Stephen F. Dale. «The Muslim Empires of the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals». — С. 96.

- ↑ Stephen F. Dale. «The Muslim Empires of the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals». — С. 70.

- ↑ М.С. Иванов. «Очерк истории Ирана». — С. 61.

- ↑ Амир Теймури Мортеза Шахриара. ««Джахангуша-и хакан» как источник по истории Ирана и Хорасана первой половины XVI в». — С. 91.

- ↑ Дж. Л. Бак-Граммонт. «Сулейман Второй и его время». — С. 226.

- ↑ Riaux Gilles. «Ethnicité et nationalisme en Iran. La cause azerbaïdjanaise» (фр.). Дата обращения: 26 февраль 2022. Архивировано 26 февраль 2022 года.

- ↑ Zeki Velidi Togan, Sur l’origine des Safavides, в Mélanges Louis Massignon, Institut français de Damas, 1957, с. 345—357.

- ↑ Shah Isma’il I (1500—24), the founder of the Safavid dynasty of Azeri origin, made the Shi’a branch of Islam the official religion of the kingdom of Persia, thus setting the Azéris firmly apart from the ethnically and linguistically similar Ottoman Turks, who were Sunni Muslims. Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2003. Europa Publications Staff, Europa Publications, Eur, Imogen Bell, Europa Publications Limited. Taylor & Francis, 2002. ISBN 1-85743-137-5, 9781857431377. Azerbaijan. History by Prof. Tadeusz Swietochowski. p. 104

- ↑ In the sixteenth century there came into being a great Persian empire. It was founded by an Azeri Turk named Ismail, leader of a religious sect which dated from the early fourteenth century, had long been confined to the Ardabil district of the north-west, and merged with Shi’ism in the mid-fifteenth. Hugh Seton-Watson. Nations and States: An Enquiry Into the Origins of Nations and the Politics of Nationalism. Taylor & Francis, 1977. ISBN 0-416-76810-5, 9780416768107

- ↑ Encyclopædia Iranica: Iran V. Peoples Of Iran. A General Survey 2011 йыл 10 август архивланған.

The Azeri Turks are Shiʿites and were founders of the Safavid dynasty.

- ↑ Roger M. Savory. «Safavids» in Peter Burke, Irfan Habib, Halil Inalci: «History of Humanity-Scientific and Cultural Development: From the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century», Taylor & Francis. 1999. Excerpt from pg 259: «Доказательства, имеющиеся в настоящее время, приводят к уверенности, что семья Сефевидов имеет местное иранское происхождение, а не тюркское, как это иногда утверждают. Скорее всего, семья возникла в Персидском Курдистане, а затем перебралась в Азербайджан, где приняла азербайджанский язык, и в конечном итоге поселилась в маленьком городе Ардебиль где-то в одиннадцатом веке (the present time, it is certain that the Safavid family was of indigenous Iranian stock, and not of Turkish ancestry as it is sometimes claimed. It is probable that the family originated in Persian Kurdistan, and later moved to Azerbaijan, where they adopted the Azari form of Turkish spoken there, and eventually settled in the small town of Ardabil sometimes during the eleventh century.)».

- ↑ 87,0 87,1 История Ирана, 1958, с. 252

- ↑ Encyclopædia Iranica: Azerbaijan X. Azeri Literature. Дата обращения: 29 май 2014. Архивировано 17 ноябрь 2011 года.

- ↑ Minorsky V. The Poetry of Shah Ismail, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 10. No. 4, 1942.

- ↑ М. Иванов. «Очерк истории Ирана». — 61 с.

- ↑ [1] 2022 йыл 14 ғинуар архивланған.

Abbās II (r. 1642-66) was himself a poet, writing Turkish verse with the pen name of «Ṯāni»

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 152

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 152—154

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 156

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 159

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 151

- ↑ 97,0 97,1 Yildirim, 2008, p. 166

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, с. 188

- ↑ 99,0 99,1 Yildirim, 2008, p. 167

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 182—185

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 191—192

- ↑ Ayfer Karakaya-Stump. The Kizilbash/Alevis in Ottoman Anatolia: Sufism, Politics and Community. — Edinburgh University Press, 2020. — С. 221.

- ↑ 103,0 103,1 Fariba Zarinebaf-Shahr Qızılbash “Heresy” and Rebellion in Ottoman Anatolia During the Sixteenth Century (инг.) // Anatolia moderna. Yeni anadolu. — 1997. — P. 1—15. Архивировано из первоисточника 3 июнь 2023.

- ↑ 104,0 104,1 Babak Rahimi Between Chieftancy and Knighthood: A Comparative Study of Ottoman and Safavid Origins // Thesis Eleven. — 2004. — Т. 76. — № 1. — С. 85—102. — DOI:10.1177/0725513604040111

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 84

- ↑ Kathryn Babayan The Safavid Synthesis: From Qizilbash Islam to Imamite Shi'ism // Iranian Studies. — 1994. — Т. 27.

- ↑ A. Allouche, «The Origins and Development of the Ottoman-Safavid conflict», p. 111

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 212—213

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 214

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 216

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 218

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 220—221

- ↑ Yildirim, 2008, p. 222

- ↑ История Ирана, 1958, с. 329

- ↑ М.С.Иванов. . — М.: МГУ, 1977. — С. 193.

- ↑ Willem Floor and Hasan Javadi The Role of Azerbaijani Turkish in Safavid Iran // Iranian StudiesAs noted above, the fact that the court language was '''Azerbaijani Turkish''' of course promoted the use of that language in the capital cities (respectively, Tabriz, Qazvin, and Isfahan). In fact, at court more Turkish was spoken than Persian. In 1607, the Carmelites reported that «the Turkish language is usually spoken and understood and the Shah [`Abbas I] and chief men and soldiers generally speak in it. The common people speak Persian, and all documents and communications are in that language.» The court ceremonial was also in Azerbaijani Turkish. The Italian traveler Pietro della Valle wrote: "that the Qizilbash grandees told him that: ‹Persian is a very soft and sweet language, and really used by women for poetry, but Turkish is manly and fit for warriors; therefore, the shah and the emirs of the state speak Turkish. Under Shah `Abbas II, the Carmelites reported that «Turki [not Osmanli Turkish] was the language of the court and widely used in Isfahan and in the north.» Chardin explicitly states about the Qizilbash, «these people, as well as their language, are so widespread in the northern part of the country, and later at court, and therefore, mistakenly all Iranians are called Qizilbash.» In 1660, Raphael du Mans wrote: «the every day language of Iran is Persian for the common people, [Azerbaijani] Turkish for the court.» According to Kaempfer, who was in Iran in the 1670s, «[Azerbaijani] Turkish is the common language at the Iranian court as well as the mother tongue of the Safavids in distinction of the language of the general populace. The use of [Azerbaijani] Turkish spread from the court to the magnates and notables and finally to all those who hope to benefit from the shah, so that nowadays it is almost considered shameful for a respectable man not to know [Azerbaijani] Turkish.» The French missionary Sanson, who lived in Iran between 1684—1695, states that Iranians regularly invoked the spiritual power of the king by using expression such as «qorban olim, din imanum padshah, bachunha dunim».

- ↑ Encyclopædia Iranica:Turkic-Iranian Contacts. Linguistic Contacts. 2013 йыл 6 февраль архивланған. «spoken Turkic was so common among all classes in Iran as to be the lingua franca»

Әҙәбиәт

[үҙгәртергә | сығанаҡты үҙгәртеү]- Пигулевская Н. В., Якубовский А. Ю., Петрушевский И. П., Строева Л. В., Беленицкий А. М. История Ирана с древнейших времён до конца XVIII века. — Издательство Ленинградского университета, 1958. — 385 с.

- Петрушевский И. П. по истории феодальных отношений в Азербайджане и Армении в XVI—начале XIX вв. — Л.: Издательство Ленинградского Государственного Ордена Ленина Университета имени А. А. Жданова, 1949. — 182 с.

- Петрушевский И. П. Государства Азербайджана в XV в. / Сборник статей по истории Азербайджана. — Вып. первый. — Б.: АН Азербайджанской ССР, 1949. — С. 153—214.

- Петрушевский И. П. Азербайджан в XVI—XVII веках. Сборник статьёй по истории Азербайджана. — Вып. первый. — Б.: АН Азербайджанской ССР, 1949. — С. 225—298.

- Эфендиев О. А. Азербайджанское государство Сефевидов в XVI веке / Редактор академик А. А. Ализаде. — Б.: Элм, 1981. — 306 с.

- Vladimir Minorsky. The Poetry of Shah Ismail // Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. — Vol. 10. No. 4, 1942.

- Ronald W. Ferrier. The Arts of Persia. — Yale University Press, 1989.

- Encyclopædia Iranica: Safavid Dynasty

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. Ṣafavid Dynasty.

- Roger Savory. Iran Under the Safavids. — Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart. Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 6. — Cambridge University Press, 1986. — 1065 с. — ISBN 0 521 20094 6.

- David Morgan. Medieval Persia 1040-1797. — Routledge, 2014. — 208 с. — ISBN 1317871405. — ISBN 9781317871408.

- Rudi Matthee Was Safavid Iran an Empire? // Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. — 2010. — Т. 53. — № 1/2, Empires and Emporia: The Orient in World Historical Space and Time (2010). — С. 233—265.

- David Thomas, John A. Chesworth. Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History. Volume 10 Ottoman and Safavid Empires (1600—1700). — BRILL, 2017. — 730 с. — ISBN 900434604X. — ISBN 9789004346048.

- Riza Yildirim. Turkomans between Two Empires: The Origins of the Qizilbash Identity in Anatolia (1447—1514). — Ankara, 2008.