Experimentos de laboratorio de especiación

Os experimentos de laboratorio de especiación son experimentos realizados sobre os catro modos de especiación: alopátrica, peripátrica, parapátrica e simpátrica; e outros procesos que implican especiación: a hibridación, reforzo, e efectos fundadores, entre outros. A maioría dos experimentos foron realizados con moscas, especialmente as moscas do vinagre Drosophila.[1] Porén, en estudos máis recentes testáronse lévedos, outros fungos e mesmo virus.

Suxeriuse que os experimentos de laboratorio non conducen a unha especiación vicariante (alopátrica e peripátrica) debido aos seus pequenos tamaños de poboación e limitado número de xeracións.[2] A maioría das estimacións de estudos da natureza indican que a especiación tarda de centos de miles a millóns de anos.[3] Por outra parte, crese que moitas especies se especiaron máis rápido e máis recentemente, como as sollas europeas Platichthys flesus, que desovan en zonas peláxicas e demersais, que se especiaron alopatricamente nunhas 3000 xeracións.[4]

Táboa de experimentos

[editar | editar a fonte]En seis publicacións intentouse compilar, revisar e analizar a investigación experimental en especiación: John Ringo, David Wood, Robert Rockwell e Harold Dowse en 1985;[5] William R. Rice e Ellen E. Hostert in 1993;[6] Ann-Britt Florin e Anders Ödeen en 2002;[2] Mark Kirkpatrick e Virginie Ravigné en 2002;[7] Jerry A. Coyne e H. Allen Orr in 2004;[1] e James D. Fry en 2009.[8] A táboa resume os estudos e datos revisados nestas publicacións. Tamén se referencias varios experimentos contemporáneos e a lista non é exhaustiva.

Na táboa que segue, os múltiples números separados por puntos e comas na columna das xeracións indican que se fixeron múltiples experimentos. As replicacións (entre parénteses) indican o número de poboacións utilizadas nos experimentos, é dicir, cantas veces se replicou o experimento. Impuxéronse varios tipos de selección ás poboacións experimentais e indícanse na columna de tipo de selección. Os resultados positivos ou negativos de cada experimento son proporcionados pola columna do illamento reprodutivo. O illamento reprodutivo precigótico significa que os individuos que se reproducían nas poboacións eran incapaces de producir descendencia (un resultado positivo, xa que se produciu illamento). O illamento reprodutivo postcigótico significa que os individuos reprodutores podían producir descendencia, pero era estéril ou inviable (un resultado positivo tamén). Os resultados negativos indícanse por "ningún", é dicir, eses experimentos non deron como resultado un illamento reprodutivo.

| Especie | Carácter | Xeracións (replicacións) [duración] | Testado | Tipo de selección | Deriva xenética estudada | Illamento reprodutivo | Referencia | Ano |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila melanogaster | Resposta de escape | 18 | Vicariante, reforzo, parapátrica/

simpátrica |

Indirecta; diverxente | Si | Precigótico | Grant & Mettler[9] | 1969 |

| D. melanogaster | Locomoción | 112 | Vicariante | Indirecta; diverxente | Non | Precigótico | Burnet & Connolly[10] | 1974 |

| D. melanogaster | Temperatura, humidade | 70–130 | Vicariante | Indirecta; diverxente | Si | Precigótico | Kilias et al.[11] | 1980 |

| D. melanogaster | Adaptación ao DDT | 600 [25 anos, +15 anos] | Vicariante | Directa | Non | Precigótico | Boake et al.[12] | 2003 |

| D. melanogaster | 17, 9, 9, 1, 1, 7, 7, 7, 7 | Vicariante; parapátrica/

simpátrica |

Directa, diverxente | Precigótico en vicariancia; ningún con fluxo xénico | Barker & Karlsson[13] | 1974 | ||

| D. melanogaster | 40; 50 | Reforzo | Directa; diverxente | Precigótico | Crossley[14] | 1974 | ||

| D. melanogaster | Locomoción | 45 | Vicariante | Directa; diverxente | Non | Ningún | van Dijken & Scharloo[15][16] | 1979 |

| D. melanogaster | Reforzo | Directa; diverxente | Precigótico | Wallace[17] | 1953 | |||

| D. melanogaster | 36; 31 | Reforzo | Directa; diverxente | Precigótico | Knight[18] | 1956 | ||

| D. melanogaster | Adaptación ao EDTA | 25, 25, 25, 14 | Semialopátrica, reforzo | Indirecta; diverxente | Non | Postcigótico | Robertson[19][20] | 1966 |

| D. melanogaster | 25 (8) | Vicariante; reforzo; parapátrica; simpátrica | Directa | Ningún | Hostert[21] | 1997 | ||

| D. melanogaster | Quetas abdominais

número |

21–31 | Vicariante | Directa | Si | Ningún | Santibanez & Waddington[22] | 1958 |

| D. melanogaster | Número de quetas esternopleurais | 32 | Vicariante, reforzo, parapátrica/

simpátrica |

Directa | Non | Ningún | Barker & Cummins[23] | 1969 |

| D. melanogaster | Fototaxe, xeotaxe | 20 | Vicariante | Non | Ningún | Markow[24][25] | 1975; 1981 | |

| D. melanogaster | Peripátrica | Si | Rundle et al.[26] | 1998 | ||||

| D. melanogaster | Vicariante; peripátrica | Si | Mooers et al.[27] | 1999 | ||||

| D. melanogaster | 12 | Reforzo | Diverxente | Precigótico | Thoday & Gibson[28] | 1962 | ||

| D. melanogaster | Ningún | Thoday & Gibson[29][30] | 1970; 1971 | |||||

| D. melanogaster | 16 | Reforzo | Indirecta | Ningún | Spiess & Wilke[31] | 1954 | ||

| D. melanogaster | Reforzo | Directa; diverxente | Precigótica | Ehrman[32][33][34][35] | 1971; 1973; 1979; 1983 | |||

| D. melanogaster | Número de quetas esternopleurais | 5; 27; 27; 1; 1; 1; 1; 1 | Parapátrica/

simpátrica |

Ningún | Chabora[36] | 1968 | ||

| D. melanogaster | Ningún | Scharloo[37] | 1967 | |||||

| D. melanogaster | 1, 1 | Coyne & Grant[38] | 1972 | |||||

| D. melanogaster | 25 | Rice[39] | 1985 | |||||

| D. melanogaster | 25 | Disruptiva | Precigótico | Rice & Salt[40] | 1988 | |||

| D. melanogaster | 35; 35 | Simpátrica | Precigótico | Rice & Salt[41] | 1990 | |||

| D. melanogaster | Niveis na comida de NaCl e CuSO4 | [3 anos en alopatría, 1 en simpatría] | Alopátrica; reforzo; simpátrica | Precigótico en alopatría, ningún en simpatría | Wallace[42] | 1982 | ||

| D. melanogaster | Reforzo | Ehrman et al.[43] | 1991 | |||||

| D. melanogaster | Reforzo | Fukatami & Moriwaki[44] | 1970 | |||||

| Drosophila simulans | Quetas escutelares, velocidade do desenvolvemento, anchura das ás; resitencia ao desecamento, fecundidade, resistencia ao etanol; exhibición de cortexo, velocidade de reapareamento, comportamento de lek; altura da pupación, posta de ovos amontoados, actividade xeral | [3 anos] | Vicariante; peripátrica | Si | Poscigótico | Ringo et al.[5] | 1985 | |

| Drosophila paulistorum | 131; 131 | Reforzo | Directa | Precigótico | Dobzhansky et al.[45] | 1976 | ||

| D. paulistorum | [5 anos] | Vicariante | Dobzhansky e Pavlovsky[46] | 1966 | ||||

| Drosophila willistoni | Adaptación ao pH | 34–122 | Vicariante | Indirecta; diverxente | Non | Precigótico | Kalisz & Cordeiro[47] | 1980 |

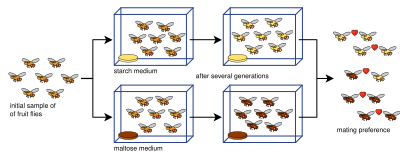

| Drosophila pseudoobscura | Fonte de carbohidratos | 12 | Vicariante | Indirecta | Si | Precigótico | Dodd[48] | 1989 |

| D. pseudoobscura | Adaptación á temperatura | 25–60 | Vicariante | Directa | Ehrman[49][50][51][52][53] | 1964;

1969 | ||

| D. pseudoobscura | Fototaxe, xeotaxe | 5–11 | Vicariante | Indirecta | Non | Precigótico | del Solar[54] | 1966 |

| D. pseudoobscura | Vicariante; peripátrica | Precigótico | Powell[55][56] | 1978; 1985 | ||||

| D. pseudoobscura | Peripátrica; vicariante | Si | Galiana et al.[57] | 1993 | ||||

| D. pseudoobscura | Fotoperíodo de temperatura; alimento | 37 (78) [33–34 meses] | Vicariante | Diverxente | Si | Ningún | Rundle[58] | 2003 |

| D. pseudoobscura & | 22; 16; 9 | Reforzo | Directa; diverxente | Precigótico | Koopman[59] | 1950 | ||

| D. pseudoobscura &

D. persimilis |

18 (4) | Directa | Precigótico | Kessler[60] | 1966 | |||

| Drosophila mojavensis | 12 | Directa | Precigótico | Koepfer[61] | 1987 | |||

| D. mojavensis | Tempo de desenvolvemento | 13 | Diverxente | Si | Ningún | Etges[62] | 1998 | |

| Drosophila adiastola | Peripátrica | Si | Precigótico | Arita & Kaneshiro[63] | 1974 | |||

| Drosophila silvestris | Peripátrica | Si | Ahearn[64] | 1980 | ||||

| Musca domestica | Xeotaxe | 38 | Vicariante | Indirecta | Non | Precigótico | Soans et al.[65] | 1974 |

| M. domestica | Xeotaxe | 16 | Vicariante | Directa; diverxente | Non | Precigótico | Hurd & Eisenburg[66] | 1975 |

| M. domestica | Peripátrica | Si | Meffert & Bryant[67] | 1991 | ||||

| M. domestica | Regan et al.[68] | 2003 | ||||||

| Bactrocera cucurbitae | Tempo de desenvolvemento | 40–51 | Diverxente | Si | Precigótico | Miyatake & Shimizu[69] | 1999 | |

| Zea mays | 6; 6 | Reforzo | Directa; diverxente | Precigótico | Paterniani[70] | 1969 | ||

| Drosophila grimshawi | Peripátrica | Jones, Widemo, & Arrendal[71] | N/A | |||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Leu & Murry[72] | 2006 | ||||||

| D. melanogaster | Reforzo | Harper & Lambert[73] | 1983 | |||||

| Tribolium castaneum | Peso da pupa | 15 (6) | Disruptiva | Halliburton & Gall[74] | 1983 | |||

| D. melanogaster | Xeotaxe | Diverxente | Lofdahl et al.[75] | 1992 | ||||

| D. pseudoobscura | [10 anos] | Moya et al.[76] | 1995 | |||||

| Neurospora | Diverxente | Dettman et al.[77] | 2008 | |||||

| S. cerevisiae | 500 | Diverxente | Dettman et al.[78] | 2007 | ||||

| Sepsis cynipsea | 35 | Martin & Hosken[79] | 2003 | |||||

| D. melanogaster | Wigby & Chapman[80] | 2006 | ||||||

| D. pseudoobscura | Colflito sexual | 48–52 (4; 4; 4) | Bacigalupe et al.[81] | 2007 | ||||

| D. serrata | Rundle et al.[82] | 2005 | ||||||

| Drosophila serrata & D. birchii | Recoñecemento de parella | 9 (3; 3) | Reforzo | Natural | Precigótico | Higgie et al.[83] | 2000 | |

| Enterobacteria phage λ | Aproveitamento do receptor de Escherichia coli | 35 ciclos (6) | Vicariante, simpátrica | Precigótico | Meyer et al.[84] | 2016 | ||

| Tetranychus urticae | Resistencia a toxina da planta hóspede | Overmeer[85] | 1966 | |||||

| T. urticae | Resistencia a toxina da planta hóspede | Fry[86] | 1999 | |||||

| Helianthus annus × H. petiolaris e H. anomalus | Híbrida | Rieseburg et al.[87] | 1996 | |||||

| S. cerevisiae | Greig et al.[88] | 2002 | ||||||

| D. melanogaster | Historia vital | Ghosh & Joshi[89] | 2012 | |||||

| Drosophila subobscura | Comportamento de apareamento | Bárbaro et al.[90] | 2015 | |||||

| Organismos dixitais | ~42,000; ~850 (20) | Ecolóxico | Postcigótico | Anderson & Harmon[91] | 2014 | |||

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | Illamento reprodutivo completo | Seike et al.[92] | 2015 | |||||

| D. pseudoobscura | Canción de cortexo | 130 | Debelle et al.[93] | 2014 | ||||

| Callosobruchus maculatus | 40 (16) | Debelle et al.[94] | 2010 |

Notas

[editar | editar a fonte]- ↑ 1,0 1,1 1,2 Coyne, Jerry A.; Orr, H. Allen (2004). Speciation. Sinauer Associates. pp. 1–545. ISBN 978-0-87893-091-3.

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 2,2 Florin, Ann-Britt & Ödeen, Anders (2002). "Laboratory environments are not conducive for allopatric speciation". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 15 (1): 10–19. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00356.x.

- ↑ Coyne, Jerry A.; Orr, H. Allen (1997). ""Patterns of Speciation in Drosophila" Revisited". Evolution 51 (1): 295–303. PMID 28568795. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb02412.x.

- ↑ Momigliano, Paolo; Jokinen, Henri; Fraimout, Antoine; Florin, Ann-Britt; Norkko, Alf; Merilä, Juha (2017). "Extraordinarily rapid speciation in a marine fish" (PDF). PNAS 114 (23): 6074–6079. PMC 5468626. PMID 28533412. doi:10.1073/pnas.1615109114. Arquivado dende o orixinal (PDF) o 26 de febreiro de 2020. Consultado o 11 de marzo de 2020.

- ↑ 5,0 5,1 Ringo, John; Wood, David; Rockwell, Robert; Dowse, Harold (1985). "An Experiment Testing Two Hypotheses of Speciation". The American Naturalist 126 (5): 642–661. doi:10.1086/284445.

- ↑ 6,0 6,1 Rice, William R. & Hostert, Ellen E. (1993). "Laboratory Experiments on Speciation: What Have We Learned in 40 Years?". Evolution 47 (6): 1637–1653. PMID 28568007. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb01257.x.

- ↑ 7,0 7,1 Kirkpatrick, Mark & Ravigné, Virginie (2002). "Speciation by Natural and Sexual Selection: Models and Experiments". The American Naturalist 159: S22–S35. PMID 18707367. doi:10.1086/338370.

- ↑ 8,0 8,1 Fry, James D. (2009). Laboratory Experiments on Speciation. In Garland, Theodore & Rose, Michael R. "Experimental Evolution: Concepts, Methods, and Applications of Selection Experiments". Pp. 631–656. doi 10.1525/california/9780520247666.003.0020

- ↑ Grant, B. S. & Mettler, L. E. (1969). "Disruptive and stabilizing selection on the" escape" behavior of Drosophila melanogaster". Genetics 62 (3): 625–637. PMC 1212303. PMID 17248452.

- ↑ Burnet, B. & Connolly, K. (1974). Activity and sexual behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. In Abeelen, J. H. V. F. (eds). The Genetics of Behaviour. North-Holland, Amsterdam. Pp. 201–258.

- ↑ Kilias, G., Alahiotis, S. N., & Pelecanos, M. (1980). "A Multifactorial Genetic Investigation of Speciation Theory Using Drosophila melanogaster". Evolution 34 (4): 730–737. JSTOR 2408027. PMID 28563991. doi:10.2307/2408027.

- ↑ Boake, C. R. B., Mcdonald, K., Maitra, S., Ganguly, R. (2003). "Forty years of solitude: life-history divergence and behavioural isolation between laboratory lines of Drosophila melanogaster". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 16 (1): 83–90. PMID 14635883. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00505.x.

- ↑ Barker, J. S. F. & Karlsson, L. J. E. (1974). "Effects of population size and selection intensity on responses to disruptive selection in Drosophila melanogaster". Genetics 78 (2): 715–735. JSTOR 2407287. doi:10.2307/2407287.

- ↑ Crossley, Stella A. (1974). "Changes in Mating Behavior Produced by Selection for Ethological Isolation Between Ebony and Vestigial Mutants of Drosophila melanogaster". Evolution 28 (4): 631–647. PMID 28564833. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1974.tb00795.x.

- ↑ van Dijken, F. R. & Scharloo, W. (1979). "Divergent selection on locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Selection response". Behavior Genetics 9 (6): 543–553. doi:10.1007/BF01067350.

- ↑ van Dijken, F. R. & Scharloo, W. (1979). "Divergent selection on locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster. II. Test for reproductive isolation between selected lines". Behavior Genetics 9 (6): 555–561. doi:10.1007/BF01067351.

- ↑ Wallace, B. (1953). "Genetic divergence of isolated populations of Drosophila melanogaster". Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress of Genetics 9: 761–764.

- ↑ Knight, G. R., Robertson, Alan, & Waddington, C. H. (1956). "Selection for sexual isolation within a species". Evolution 10 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1956.tb02825.x.

- ↑ Robertson, Forbes W. (1966). "A test of sexual isolation in Drosophila". Genetical Research 8 (2): 181–187. PMID 5922518. doi:10.1017/S001667230001003X.

- ↑ Robertson, Forbes W. (1966). "The ecological genetics of growth in Drosophila 8. Adaptation to a New Diet". Genetical Research 8 (2): 165–179. PMID 5922517. doi:10.1017/S0016672300010028.

- ↑ Hostert, Ellen E. (1997). "Reinforcement: a new perspective on an old controversy". Evolution 51 (3): 697–702. PMID 28568598. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb03653.x.

- ↑ Koref Santibañez, S. & Waddington, C. H. (1958). "The origin of sexual isolation between different lines within a species". Evolution 12 (4): 485–493. JSTOR 2405959. doi:10.2307/2405959.

- ↑ Barker, J. S. F. & Cummins, L. J. (1969). "The effect of selection for sternopleural bristle number in mating behaviour in Drosophila melanogaster". Genetics 61 (3): 713–719. PMC 1212235. PMID 17248436.

- ↑ Markow, Therese Ann (1975). "A genetic analysis of phototactic behavior in Drosophila melanogaster". Genetics 79 (3): 527–534. PMC 1213291. PMID 805084.

- ↑ Markow, Therese Ann (1981). "Mating preferences are not predictive of the direction of evolution in experimental populations of Drosophila". Science 213 (4514): 1405–1407. PMID 17732575. doi:10.1126/science.213.4514.1405.

- ↑ Rundle, H. D., Mooers, Arne Ø. & Whitlock, Michael C. (1998). "Single founder-flush events and the evolution of reproductive isolation". Evolution 52 (6): 1850–1855. PMID 28565304. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1998.tb02263.x.

- ↑ Mooers, Arne Ø., Rundle, Howard D. & Whitlock, Michael C. (1999). "The effects of selection and bottlenecks on male mating success in peripheral isolates". American Naturalist 153 (4): 437–444. PMID 29586617. doi:10.1086/303186.

- ↑ Thoday, J. M. & Gibson, J. B. (1962). "Isolation by disruptive selection". Nature 193 (4821): 1164–1166. PMID 13920720. doi:10.1038/1931164a0.

- ↑ Thoday, J. M. & Gibson, J. B. (1970). "The probability of isolation by disruptive selection". Nature 104 (937): 219–230. doi:10.1086/282656.

- ↑ Scharloo, W. (1971). "Reproductive isolation by disruptive selection: Did it occur?". American Naturalist 105 (941): 83–86. doi:10.1086/282706.

- ↑ Spiess, E. B. & Wilke, C. M. (1984). "Still another attempt to achieve assortive mating by disruptive selection in Drosophila". Evolution 38 (3): 505–515. JSTOR 2408700. doi:10.2307/2408700.

- ↑ Ehrman, Lee (1971). "Natural selection and the origin of reproductive isolation". American Naturalist 105 (945): 479–483. doi:10.1086/282739.

- ↑ Ehrman, Lee (1973). "More on natural selection and the origin of reproductive isolation". American Naturalist 107 (954): 318–319. doi:10.1086/282835.

- ↑ Ehrman, Lee (1979). "Still more on natural selection and the origin of reproductive isolation". American Naturalist 113 (1): 148–150. doi:10.1086/283371.

- ↑ Ehrman, Lee (1983). "Fourth report on natural selection for the origin of reproductive isolation". American Naturalist 121 (2): 290–293. doi:10.1086/284059.

- ↑ Chabora, Alice J. (1968). "Disruptive selection for sternopleural chaeta number in various strains of Drosophila melanogaster". American Naturalist 102 (928): 525–532. doi:10.1086/282565.

- ↑ Scharloo, W., Hoogmoed, M. S. & Kuile, A. T. (1967). "Stabilizing and disruptive selection on a mutant character in Drosophila. I. The phenotypic variance and its components.". Genetics 56 (4): 709–726. PMC 1211648. PMID 6061662.

- ↑ Coyne, Jerry A. & and Grant, Bruce (1972). "Disruptive selection on I-maze activity in Drosophila melanogaster". Genetics 71 (1): 185–188. PMC 1212770. PMID 17248572.

- ↑ Rice, W. R. (1985). "Disruptive selection on habitat preference and the evolution of reproductive isolation: an exploratory experiment". Evolution 39 (3): 645–656. PMID 28561974. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00401.x.

- ↑ Rice, William R. & Salt, George, W. (1988). "Speciation via disruptive selection on habitat preference". American Naturalist 131 (6): 911–917. doi:10.1086/284831.

- ↑ Rice, William R. & Salt, George, W. (1990). "The evolution of reproductive isolation as a correlated character under sympatric conditions: experimental evidence". Evolution 44 (5): 1140–1152. JSTOR 2409278. doi:10.2307/2409278.

- ↑ Wallace, B. (1982). "Drosophila melanogaster populations selected for resistances to NaCl and CuSO4 in both allopatry and sympatry". Journal of Heredity 73 (1): 35–42. PMID 6802898. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109572.

- ↑ Ehrman, Lee, White, Marney A. & Wallace, B. (1991). A long-term study involving Drosophila melanogaster and toxic media. In Hecht, M. K., Wallace, B., & Maclntyre, R. J. (eds). Evolutionary biology, vol. 25. Plenum Press, New York. Pp. 175–209

- ↑ Fukatami, A & Moriwaki, D. (1970). "Selection for sexual isolation in Drosophila melanogaster by a modification of Koopman's method". The Japanese Journal of Genetics 45 (3): 193–204. doi:10.1266/jjg.45.193.

- ↑ Dobzhansky, Theodosius; Pavlovsky, O.; Powell, J. R. (1976). "Partially Successful Attempt to Enhance Reproductive Isolation Between Semispecies of Drosophila paulistorum". Evolution 30 (2): 201–212. JSTOR 2407696. PMID 28563045. doi:10.2307/2407696.

- ↑ Dobzhansky, Theodosius & Pavlovsky, O. (1966). "Spontaneous origin of an incipient species in the Drosophila paulistorum complex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 55 (4): 723–733. PMC 224220. PMID 5219677. doi:10.1073/pnas.55.4.727.

- ↑ de Oliveira, Alice Kalisz & Cordeiro, Antonio Rodrigues (1980). "Adaptation of Drosophila willistoni experimental populations to extreme pH medium". Heredity 44: 123–130. doi:10.1038/hdy.1980.11.

- ↑ Dodd, Diane M. B. (1989). "Reproductive Isolation as a Consequence of Adaptive Divergence in Drosophila pseudoobscura". Evolution 43 (6): 1308–1311. JSTOR 2409365. PMID 28564510. doi:10.2307/2409365.

- ↑ Ehrman, Lee (1964). "Genetic divergence in M. Vetukhiv's experimental populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura 1. Rudiments of sexual isolation". Genetical Research 5: 150–157. doi:10.1017/S0016672300001099.

- ↑ Mouradael, K. (1965). "Genetic divergence in M. Vetukhiv's experimental populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura 2. Longevity". Genetical Research 6: 139–146. PMID 14297592. doi:10.1017/S0016672300004006.

- ↑ Anderson, Wyatt, W. (1966). "Genetic divergence in M. Vetukhiv's experimental populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura 3. Divergence in Body Size". Genetical Research 7 (2): 255–266. doi:10.1017/S0016672300009666.

- ↑ Kitagawa, Osamu (1967). "Genetic divergence in M. Vetukhiv's experimental populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura: IV. Relative viability". Genetical Research 10 (7): 303–312. doi:10.1017/S001667230001106X.

- ↑ Ehrman, Lee (1969). "Genetic divergence in M. Vetukhiv's experimental populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura. 5. A further study of rudiments of sexual isolation". American Midland Naturalist 82 (1): 272–276. JSTOR 2423835. doi:10.2307/2423835.

- ↑ del Solar, Eduardo (1966). "Sexual isolation caused by selection for positive and negative phototaxis and geotaxis in Drosophila pseudoobscura". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 56 (2): 484–487. PMC 224398. PMID 5229969. doi:10.1073/pnas.56.2.484.

- ↑ Powell, Jeffrey R. (1978). "The Founder-Flush Speciation Theory: An Experimental Approach". Evolution 32 (3): 465–474. JSTOR 2407714. doi:10.2307/2407714.

- ↑ Dodd, Diane M. B. & Powell, Jeffrey R. (1985). "Founder-Flush Speciation: An Update of Experimental Results with Drosophila". Evolution 39 (6): 1388–1392. PMID 28564258. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb05704.x.

- ↑ Galiana, Augustí, Moya, Andres & Ayala, Fransisco J. (1993). "Founder-flush speciation in Drosophila pseudoobscura: a large scale experiment". Evolution 47 (2): 432–444. PMID 28568735. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb02104.x.

- ↑ Rundle, Howard D. (2003). "Divergent environments and population bottlenecks fail to generate premating isolation in Drosophila pseudoobscura". Evolution 57 (11): 2557–2565. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01499.x.

- ↑ Koopman, Karl F. (1950). "Natural Selection for Reproductive Isolation Between Drosophila pseudoobscura and Drosophila persimilis". Evolution 4 (2): 135–148. JSTOR 2405390. doi:10.2307/2405390.

- ↑ Kessler, Seymour (1966). "Selection For and Against Ethological Isolation Between Drosophila pseudoobscura and Drosophila persimilis". Evolution 20 (4): 634–645. JSTOR 2406597. PMID 28562900. doi:10.2307/2406597.

- ↑ Koepfer, H. Roberta (1987). "Selection for Sexual Isolation Between Geographic Forms of Drosophila mojavensis. I Interactions Between the Selected Forms". Evolution 41 (1): 37–48. JSTOR 2408971. PMID 28563762. doi:10.2307/2408971.

- ↑ Etges, W. J. (1998). "Premating isolation is determined by larval rearing substrates in cactophilis Drosophila mojavensis. IV. Correlated responses in behavioral isolation to artificial selection on a life-history trait". American Naturalist 152 (1): 129–144. PMID 18811406. doi:10.1086/286154.

- ↑ Arita, Lorna H. & Kaneshiro, Kenneth Y. (1979). "Ethological Isolation Between Two Stocks of Drosophila Adiastola Hardy". Hawaiian Entomological Society 23 (1): 31–34.

- ↑ Ahearn, J. N. (1980). "Evolution of behavioral reproductive isolation in a laboratory stock of Drosophila silvestris". Experientia 36 (1): 63–64. doi:10.1007/BF02003975.

- ↑ Soans, A. Benedict; Pimentel, David; Soans, Joyce S. (1974). "Evolution of Reproductive Isolation in Allopatric and Sympatric Populations". The American Naturalist 108 (959): 117–124. doi:10.1086/282889.

- ↑ Hurd, L. E. & Eisenberg, Robert M. (1975). "Divergent Selection for Geotactic Response and Evolution of Reproductive Isolation in Sympatric and Allopatric Populations of Houseflies". The American Naturalist 109 (967): 353–358. doi:10.1086/283002.

- ↑ Meffert, L. M. & Bryant, E. H. (1991). "Mating propensity and courtship behavior in serially bottlenecked lines of the housefly". Evolution 45 (2): 293–306. PMID 28567864. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb04404.x.

- ↑ Regan, J. L.; Meffert, L. M.; Bryant, E. H. (2003). "A direct experimental test of founder-flush effects on the evolutionary potential for assortative mating". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 16 (2): 302–312. PMID 14635869. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00521.x.

- ↑ Miyatake, Takahisa & Shimizu, Toru (1999). "Genetic correlations between life-history and behavioral traits can cause reproductive isolation". Evolution 53 (1): 201–208. JSTOR 2640932. PMID 28565193. doi:10.2307/2640932.

- ↑ Paterniani, E. (1969). "Selection for Reproductive Isolation between Two Populations of Maize, Zea mays L.". Evolution 23 (4): 534–547. JSTOR 2406851. doi:10.2307/2406851.

- ↑ Ödeen, Anders & Florin, Ann-Britt (2002). "Sexual selection and peripatric speciation: the Kaneshiro model revisited". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 15 (2): 301–306. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00378.x.

- ↑ Leu, J. Y. & Murray, A. W. (2006). "Experimental evolution of mating discrimination in budding yeast". Current Biology 16 (3): 280–286. PMID 16461281. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.028.

- ↑ Harper, A. A. & Lambert, D. M. (1983). "The population genetics of reinforcing selection". Genetica 62 (1): 15–23. doi:10.1007/BF00123305.

- ↑ Halliburton, Richard & Gall, G. A. E. (1981). "Disruptive selection and assortative mating in Tribolium castaneum". Evolution 35 (5): 829–843. PMID 28581046. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1981.tb04947.x.

- ↑ Lofdahl, L. Katharine; Hu, Dan; Ehrman, Lee; Hirsch, Jerry; Skoog, Linda (1992). "Incipient reproductive isolation and evolution in laboratory Drosophila melanogaster selected for geotaxis". Animal Behaviour 44 (4): 783–786. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80307-0.

- ↑ Moya, A.; Galiana, A.; Ayala, F. J. (1995). "Founder-effect speciation theory: failure of experimental corroboration". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 92 (9): 3983–3986. PMC 42086. PMID 7732017. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.9.3983.

- ↑ Dettman, Jeremy R.; Anderson, James B.; Kohn, Linda M. (2008). "Divergent adaptation promotes reproductive isolation among experimental populations of the filamentous fungus Neurospora". BMC Evolutionary Biology 8 (35): 35. PMC 2270261. PMID 18237415. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-35.

- ↑ Dettman, Jeremy R.; Sirjusingh, Caroline; Kohn, Linda M.; Anderson, James B. (2007). "Incipient speciation by divergent adaptation and antagonistic epistasis in yeast". Nature 447 (7144): 585–588. PMID 17538619. doi:10.1038/nature05856.

- ↑ Martin, Oliver Y. & Hosken, David J. (2003). "The evolution of reproductive isolation through sexual conflict". Nature 423 (6943): 979–982. PMID 12827200. doi:10.1038/nature01752.

- ↑ Wigby, S. & Chapman, T. (2006). "No evidence that experimental manipulation of sexual conflict drives premating reproductive isolation in Drosophila melanogaster". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 19 (4): 1033–1039. PMID 16780504. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01107.x.

- ↑ Bacigalupe, L. D.; Crudgington, H. S.; Hunter, F.; Moore, A. J.; Snook, R. R. (2007). "Sexual conflict does not drive reproductive isolation in experimental populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 20 (5): 1763–1771. PMID 17714294. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01389.x.

- ↑ Rundle, Howard D.; Chenoweth, Steve F.; Doughty, Paul; Blows, Mark W. (2005). "Divergent selection and the evolution of signal traits and mating preferences". PLoS Biology 3 (11): e368. PMC 1262626. PMID 16231971. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030368.

- ↑ Higgie, Megan; Chenoweth, Steve F.; Blows, Mark W. (2000). "Natural selection and the reinforcement of mate recognition" (PDF). Science 290 (5491): 519–521. PMID 11039933. doi:10.1126/science.290.5491.519.

- ↑ Meyer, Justin R.; Dobias, Devin T.; Medina, Sarah J.; Servilio, Lisa; Gupta, Animesh; Lenski, Richard E. (2016). "Ecological speciation of bacteriophage lambda in allopatry and sympatry". Science 354 (6317): 1301–1304. PMID 27884940. doi:10.1126/science.aai8446.

- ↑ Overmeer, W. P. J. (1966). "Intersterility as a Consequence of Insecticide Selections in Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae)". Nature 209 (321): 321. doi:10.1038/209321a0.

- ↑ Fry, James D. (1999). "The role of adaptation to host plants in the evolution of reproductive isolation: Negative evidence from Tetranychus urticae Koch". Experimental & Applied Acarology 23 (5): 379–387. doi:10.1023/A:1006245711950.

- ↑ Rieseberg, L. H.; Sinervo B.; Linder, C. R.; Ungerer, M.C.; Arias, D. M. (1996). "Role of Gene Interactions in Hybrid Speciation: Evidence from Ancient and Experimental Hybrids". Science 272 (5262): 741–745. PMID 8662570. doi:10.1126/science.272.5262.741.

- ↑ Greig, Duncan; Louis, Edward J.; Borts, Rhona H.; Travisano, Michael (2002). "Hybrid speciation in experimental populations of yeast". Science 298 (5599): 1773–1775. PMID 12459586. doi:10.1126/science.1076374.

- ↑ Ghosh, Shampa M. & Joshi, Amitabh (2012). "Evolution of reproductive isolation as a by-product of divergent life-history evolution in laboratory populations of Drosophila melanogaster". Ecology and Evolution 2 (12): 3214–3226. PMC 3539013. PMID 23301185. doi:10.1002/ece3.413.

- ↑ Bárbaro, Margarida; Mira, Mário S.; Fragata, Inês; Simões, Pedro; Lima, Margarida; Lopes-Cunha, Miguel; Kellen, Bárbara; Santos, Josiane; Varela, Susana A. M.; Matos, Margarida; Magalhães, Sara (2015). "Evolution of mating behavior between two populations adapting to common environmental conditions". Ecology and Evolution 5 (8): 1609–1617. PMC 4409410. PMID 25937905. doi:10.1002/ece3.1454.

- ↑ Anderson, Carlos J. R. & Harmon, Luke (2014). "Ecological and Mutation-Order Speciation in Digital Organisms". The American Naturalist 183 (2): 257–269. PMID 24464199. doi:10.1086/674359.

- ↑ Seike, Taisuke; Nakamura, Taro; Shimoda, Chikashi (2015). "Molecular coevolution of a sex pheromone and its receptor triggers reproductive isolation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe". PNAS 112 (14): 4405–4410. PMC 4394278. PMID 25831518. doi:10.1073/pnas.1501661112.

- ↑ Debelle, Allan; Ritchie, Michael G.; Snook, Rhonda R. (2014). "Evolution of divergent female mating preference in response to experimental sexual selection". Evolution 68 (9): 2524–2533. PMC 4262321. PMID 24931497. doi:10.1111/evo.12473.

- ↑ Fricke, C; Andersson, C.; Arnqvist, G. (2010). "Natural selection hampers divergence of reproductive traits in a seed beetle". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23 (9): 1857–1867. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02050.x.

Véxase tamén

[editar | editar a fonte]Outros artigos

[editar | editar a fonte]