防疫線 (医学)

防疫線(ぼうえきせん、仏: Cordon sanitaire、(フランス語発音: [kɔʁdɔ̃ sanitɛʁ]、英: sanitary cordon)は、コミュニティや地域、国のような地理的な指定区域に出入りする人々の移動を制限することである[1]。

元々は、感染症の広がりを防ぐために使われた障壁を指していた。また、ソ連に対抗してジョージ・ケナンが採用した封じ込め政策のような、不必要で危険なイデオロギーの広がりを防ぐものとして、英語で比喩的に使われていた[2]。

起源

[編集]この用語は1821年にから使われ、その時はリシュリュー公爵が、黄熱病がフランスに広がる前に、フランスとスペインとの国境にフランス軍を展開した[3][4]。

定義

[編集]一般に、防疫線は感染症のアウトブレイクあるいはエピデミック中の地域の周囲または二国間の国境沿いに設置される。一度設置されたならば、感染症が広がる地域から出入り出来なくなる。最も極端な場合、感染がなくなるまで撤去されない[5]。伝統的に、防疫線は物理的なものであり、フェンスや壁が作られ、軍がパトロールし、内部では援助なしで感染症と戦うことになった。一部の事例では、「逆防疫線」(予防隔離として知られる)が、健康なコミュニティで感染が広がらないように、行われる可能性もある。公衆衛生の専門家は、検疫や隔離を伴う防疫線を社会距離拡大戦略を通して微生物の病原体の伝播を防ぐ非薬理学的介入として盛り込んでいる[6]。

現代では、防疫線は、感染経路や治療、予防に対する理解が向上したことにより、めったに使われない。

- 感染性が非常に強い。

- 死亡率が非常に高い。

- 治療法が存在しない、または治療が難しい。

- ワクチンが存在しない、または大人数の免疫を構築する他の手段が乏しい。

といった状況下での有効な介入法として残っている。

新型コロナウイルス感染症の世界的流行では、感染症の封じ込め策として、世界中で防疫線が設置された[7]。

歴史

[編集]16世紀

[編集]1523年、ビルグにおけるペスト流行で、マルタの他の地域に広がらないように衛兵により防疫線が設置された[8]。

17世紀

[編集]- 1655年のペストの流行(en)で、マルタのŻabbarで防疫線が設置された。感染症が他の集落に広がり、抑制策が行われ、死者20人で抑え込むことに成功した[9]。

- よく知られているように、1666年5月、イギリスのen:Eyam村で腺ペスト流行後に防疫線が設置された。その後の14ヶ月で、住民の80%が亡くなった[10]。村の周囲に石が置かれ、ペスト流行が収まった1667年11月まで境界を超えて出入りできなかった。近隣の集落から村に食料が提供され、防疫線沿いの指定場所で救助物資を置き、流水やビネガーで消毒した硬貨で支払った[11]:72。

18世紀

[編集]- 1708年から1712年までの大北方戦争におけるペストの流行で、シュトラールズント、ヘルシンゲル、ケーニヒスベルクといった感染症の影響を受けた地域で防疫線が設置された。一方はプロイセン公国全域に設置され、もう一方は検疫所をen:Saltholmに置き、スコーネ地方とエーレスンド海峡沿いのデンマークの島との間に設置された[12]。

- 1770年、オーストリア皇后マリア・テレジアは、ペストに感染した人々や物資が国境を越えないように、オーストリア(ハプスブルク帝国)とオスマン帝国との間に防疫線を設置させた。綿と木は数週間倉庫に留め置かれ、農民は金銭を支払って牧草で眠りにつかせ、病気の兆候が見られるかどうかを監視した。旅行者は、通常ならば21日間、オスマン領でペストが流行していると確認されたら48日間まで検疫を受けさせられた。防疫線は1871年まで維持され、防疫線が設置された後はオーストリア領でペストの大規模流行はみられなかったが、オスマン帝国は19世紀半ばまで頻繁にペストのエピデミックに苦しめられた[13]。

- 1793年のフィラデルフィアにおける黄熱病の流行(en)で、市内に向かう道路と橋が、感染症が広がるのを防ぐために地元の軍から派遣された兵士により封鎖された。これは、黄熱病の伝播機構が十分に理解される前だった[14][要ページ番号][15]。

19世紀

[編集]- 1813年から1814年までのマルタにおけるペストの流行(en)で、主要都市(バレッタ、Floriana、Three Cities)や死亡率が高い地方自治体(ビルキルカラ、Qormi、Żebbuġ、Xagħra)では出入りを防ぐために軍の防疫線が設置された[16]。

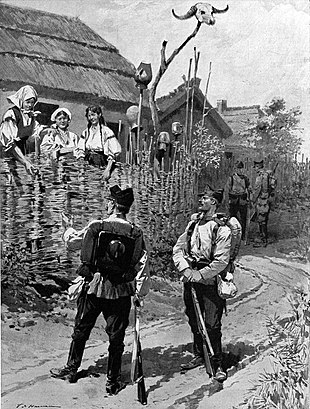

- 防疫線という用語が最初に使われたのは1821年である。リシュリュー公爵がピレネー山脈にあるフランスとスペインとの国境にフランス軍3,000人を展開した。伝えられるところでした黄熱病がバルセロナからフランスに広がるのを防ぐためとされたが[3]、実際にはスペイン立憲革命由来の自由主義の思想が広がらないようにするためだったとされる[4]。

- 1821年の黄熱病の流行でバルセロナが荒廃し、15万人がいた街全体で防疫線が設置された。4ヶ月間で18,000人から20,000人が亡くなった[13]。

- 1830年のロシアにおけるコレラの流行(en)で、モスクワには軍の防疫線が設置され、市内につながる道路は旅行を防ぐために掘り起こされ、4ヶ所を除く市の入口が封鎖された[13]。

- 1856年の黄熱病の流行で、防疫線がアメリカのジョージア州の一部の都市で設置され、まずまずの成功を収めた[17]。

- 1869年、アドリヤン・プルースト(小説家マルセル・プルーストの父)は、インドから発生しヨーロッパとアフリカを脅かしていたコレラ(en)の広がりを制御するために防疫線を使うことを提案した。また、インドや東南アジアからヨーロッパに向かうすべての舟をスエズで検疫することも提案したが、全般的に彼の提案は受け入れられなかった[18][19]。

- 1882年、テキサス州ブラウンズビルとメキシコ北部で強い病原性を持つ黄熱病の流行を受けて、市の北部180マイルのところに東のメキシコ湾から西のリオ・グランデ川まで防疫線が設置された。北に向かう人々は10日間の検疫を受けて感染症にかかっていないことを確認されるまで、その先に進めなかった[13]。

- 1888年、黄熱病の流行で、フロリダ州ジャクソンビルは、フロリダ州知事Edward A. Perryの命令により防疫線が設置された[20]。

- 1899年、ホノルルでのペストの流行はChinatown周辺の防疫線により管理された。感染症の制御の取り組みにおいて、周囲を有刺鉄線で囲み、人々の所有物と家が燃やされた[21]。

20世紀

[編集]- 1900年から1904年までのサンフランシスコにおけるペストの流行(en)で、サンフランシスコのChinatownが防疫線の対象になった[22]。

- 1902年、ルイジアナ州はイタリアの移民がニューオーリンズの港に上陸しないように防疫線を設置した。船の会社は損害賠償の訴訟を起こしたが、州の防疫線を設置する権利がen:Compagnie Francaise de Navigation a Vapeur v. Louisiana Board of Healthで支持された。

- 1903年から1914年まで、ベルギー植民地帝国はベルギー領コンゴの東部州でトリパノソーマ症(睡眠病)の流行を制御するために防疫線が設置された[23]。

- スペインかぜの流行

- スペインかぜは急速に広がり、一般に、防疫線を設置する時間がなかった。しかし、感染症の広がりを防ぐために、Gunnisonは、1918年の終わりの2ヶ月間、周囲地域から孤立した。すべてのハイウェイが郡の路線付近でバリケードにより封鎖され、列車の車掌は、すべての乗客に対して、Gunnison内で列車の外に出たならば拘束され5日間の検疫を受けさせられると警告した。これらの予防隔離により、Gunnisonでスペインかぜによる死者は出なかった[24]。

- 当時のアメリカ領サモア知事John Martin Poyerが、やってくる船からの予防隔離を島で行い、死者を0人に収めることに成功した[25]。対照的に、近隣のニュージーランド領西サモアでは最もひどい打撃を受け、感染率が90%で成人の20%超が亡くなった[26]。

- 1918年後半、スペインは、出入国管理、道路封鎖、鉄道による移動の制限、病人が乗っている船の上陸を防ぐための海上の防疫線の設置でスペインかぜの広がりを防ごうとしたが、すでに流行が進行していたために失敗した[27][要ページ番号]。

- 1972年のユーゴスラビアにおける天然痘の流行(en)では、1万人超の人々が防疫線が設置された村の中や道路封鎖された地域に隔離された。住民会議が全般的に禁止され、すべての境界が閉鎖され、不要不急の外出がすべて禁止された。

- 1995年、ザイールのキクウィトでエボラ出血熱の流行を制御するために防疫線が使われた[28][29][30]。モブツ・セセ・セコ大統領はキクウィトを軍で包囲させ、すべての航空便を一時停止させた。キクウィト内部では、WHOとザイールの医療チームがさらに防疫線を設置して、墓と治療区画を一般人から隔離した[31][要ページ番号]。

21世紀

[編集]- 2003年のカナダにおけるSARSの流行(en)で、コミュニティ隔離が行われ、感染症の伝播減少に成功した[32]。

- 2003年の中国本土、香港、台湾、シンガポールにおけるSARSの流行で、SARS流行地域からの旅行者、仕事や学校で感染が疑われる人と接触した人々、そして少数例ながら罹患率が高い団地の住民に対して大規模な隔離が行われた[33] 。中国では、地方のすべての村が隔離され、出入りが禁止された。河北省のある村は、2003年4月12日から5月13日まで隔離された。何万人の人々が防疫線が差し迫っていると知って避難したために、感染が広がった可能性がある[34]。

- 2014年8月、西アフリカにおけるエボラ出血熱の流行で、最も感染が広がっている地域の一部で防疫線が設置された[35][5]。2014年8月19日、リベリア政府は首都モンロビアのWest Point全域を隔離して、全国で夜間外出禁止令を発令した[36][37]。この地域での防疫線は8月30日まで継続された。大臣のLewis Brownは、この措置が住民のスクリーニング、テスト、治療を容易にするために行われたと述べた[38]。

- 2020年1月、新型コロナウイルス感染症の流行に伴い、中国の武漢で防疫線が設置された(en)[39]。流行が広がるにつれ、旅行制限が中国の人口の半分以上に影響を与え、2020年3月に13億人に影響を与えたインドのロックダウン(en)が超えるまで、歴史上で最大の防疫線とされていた[40][41]。2020年4月頃には、新型コロナウイルス感染症の世界的流行を受けて、世界人口の半分以上がMalaysian movement control order(2020年–2021年)[42]やイタリア全域のロックダウン(en)[43]のように、何らかの形で90ヶ国以上のロックダウン[44]の下にあった。

大衆文化

[編集]- 防疫線がアルベール・カミュの1947年の小説ペストで狂言回しとして使われた。

- 1995年の映画アウトブレイクでは、アフリカから持ち込まれたエボラに似たウィルスがカリフォルニアの小さな町でエピデミックを起こし、アメリカ軍が町の周囲に防疫線を設置した。

- 2002年の映画28日後...では、ウィルス感染で壊滅したイギリスで設置された防疫線を描写している。

- en:Thomas Mullenの小説en:The Last Town on Earth(2006年)では、1918年にワシントン州コモンウェルスでスペインかぜを防ぐために予防隔離を行ったものの、さまよう兵士により感染症が広がった。

- 2006年の小説WORLD WAR Zでは、イスラエルがゾンビを侵入させないように防疫線を設置した。

- 2011年の映画コンテイジョンでは、髄膜脳炎のウィルスの広がりを防ぐためにシカゴで防疫線が設置された。

- 2014年のベルギーのテレビシリーズCordonでは、アントウェルペンの鳥インフルエンザ封じ込めのために防疫線が設置された。

- 2016年のテレビリミテッドシリーズContainmentでは、アトランタの感染性ウィルス封じ込めのために防疫線が設置された。

関連項目

[編集]脚注

[編集]- ^ Rothstein, Mark A. (2015). “From SARS to Ebola: Legal and Ethical Considerations for Modern Quarantine”. Indiana Health Law Review 12 (1): 227. doi:10.18060/18963. SSRN 2499701.

- ^ Fisher, Harold H. (1927). The Famine in Soviet Russia, 1919–1923. New York: Macmillan. p. 25

- ^ a b Taylor, James (1882). The Age We Live In: A History of the Nineteenth Century. Oxford University. p. 222

- ^ a b Nichols, Irby C. (1972). The European Pentarchy and the Congress of Verona, 1822. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-94-010-2725-0

- ^ a b McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (2014年8月12日). “Using a Tactic Unseen in a Century, Countries Cordon Off Ebola-Racked Areas”. The New York Times 14 August 2014閲覧。

- ^ Markel, Howard; Lipman, Harvey B.; Navarro, J. Alexander; Sloan, Alexandra; Michalsen, Joseph R.; Stern, Alexandra Minna; Cetron, Martin S. (8 August 2007). “Nonpharmaceutical Interventions Implemented by US Cities During the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic”. JAMA 298 (6): 644–654. doi:10.1001/jama.298.6.644. PMID 17684187.

- ^ Baird, Robert P. (11 March 2020). “What It Means to Contain and Mitigate the Coronavirus”. The New Yorker 2021年1月31日閲覧。.

- ^ Savona-Ventura, Charles. The Medical History of the Maltese Islands: Medieval Medicine. University of Malta. オリジナルの3 March 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Savona-Ventura, Charles (2015). Knight Hospitaller Medicine in Malta [1530–1798]. Self-published. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-1-326-48222-0

- ^ Race, Philip (1995). “Some Further Consideration of the Plague in Eyam, 1665/6”. Local Population Studies 54: 56–65. PMID 11639747.

- ^ Paul, David. Eyam: Plague Village. Amberley Publishing, 2012.

- ^ Frandsen, Karl-Erik (2010). The Last Plague in the Baltic Region, 1709–1713. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 87-635-0770-6

- ^ a b c d Kohn, George C. (2007). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present. Infobase Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 1-4381-2923-8

- ^ Powell, J. H. (2014). Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793. Studies in Health, Illness, and Caregiving. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-9117-9

- ^ Arnebeck, Bob (30 January 2008). “A Short History of Yellow Fever in the US”. Destroying Angel: Benjamin Rush, Yellow Fever and the Birth of Modern Medicine

- ^ Mangion, Fabian (19 May 2013). “Maltese islands devastated by a deadly epidemic 200 years ago”. Times of Malta. オリジナルの12 March 2020時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Campbell, Henry Fraser (1879). “The Yellow Fever Quarantine of the Future, as Organized upon the Portability of Atmospheric Germs and upon the Non-Contagiousness of the Disease”. Public Health Papers and Reports 5: 131–144. PMC 2272165. PMID 19600008.

- ^ Carter, William C. (2002). Marcel Proust: A Life. Yale University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-300-09400-0

- ^ Weissmann, Gerald (January 2015). “Ebola, Dynamin, and the Cordon Sanitaire of Dr. Adrien Proust”. The FASEB Journal 29 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1096/fj.15-0101ufm. PMID 25561464.

- ^ “Epidemic Disease and the Establishment of the Board of Health”. Pestilence, Potions, and Persistence: Early Florida Medicine. Florida Memory. p. 2. 2021年1月31日閲覧。

- ^ Onion, Rebecca (15 August 2014). “The Disastrous Cordon Sanitaire Used on Honolulu's Chinatown in 1900”. Slate 2021年1月31日閲覧。.

- ^ Skubik, Mark M. (May 2002). Public Health Politics and the San Francisco Plague Epidemic of 1900–1904 (PDF) (Thesis). San Jose State University. doi:10.31979/etd.hq5x-ph4v。

- ^ Lyons, Maryinez (January 1985). “From 'Death Camps' to Cordon Sanitaire: The Development of Sleeping Sickness Policy in the Uele District of the Belgian Congo, 1903–1914”. The Journal of African History 26 (1): 69–91. doi:10.1017/S0021853700023094. JSTOR 181839.

- ^ “Gunnison”. Center for the History of Medicine, University of Michigan. 2021年1月31日閲覧。

- ^ Okin, Peter Oliver (January 2012). The Yellow Flag of Quarantine: An Analysis of the Historical and Prospective Impacts of Socio-Legal Controls Over Contagion (PhD). University of South Florida. p. 232.

- ^ Patterson, Michael Robert (21 December 2005). “John Martin Poyer, Commander, United States Navy”. Arlington National Cemetery Website. 2021年1月31日閲覧。

- ^ Davis, Ryan A. (2013). The Spanish Flu: Narrative and Cultural Identity in Spain, 1918. Springer. ISBN 1-137-33921-7

- ^ Garrett, Laurie (14 August 2014). “Heartless but Effective: I've Seen 'Cordon Sanitaire' Work Against Ebola”. The New Republic 2021年1月31日閲覧。.

- ^ “Outbreak of Ebola Viral Hemorrhagic Fever – Zaire, 1995”. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 44 (19): 381–382. (19 May 1995). PMID 7739512.

- ^ Hoffmann, Rachel Kaplan; Hoffmann, Keith (19 February 2015). “Ethical Considerations in the Use of Cordons Sanitaires”. Clinical Correlations. オリジナルの2015-02-22時点におけるアーカイブ。 2021年1月31日閲覧。.

- ^ Garrett, Laurie (2011). Betrayal of Trust: The Collapse of Global Public Health. Hachette Books. ISBN 1-4013-0386-2

- ^ Bondy, Susan J; Russell, Margaret L; Laflèche, Julie ML; Rea, Elizabeth (2009). “Quantifying the impact of community quarantine on SARS transmission in Ontario: estimation of secondary case count difference and number needed to quarantine”. BMC Public Health 9: 488. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-488. PMC 2808319. PMID 20034405.

- ^ Cetron, Martin; Maloney, Susan; Koppaka, Ram; Simone, Patricia (2004). “Isolation and Quarantine: Containment Strategies for SARS 2003”. Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak. National Academies Press. pp. 71–83. doi:10.17226/10915. ISBN 0-309-59433-2

- ^ Rothstein, Mark A.; Alcalde, M. Gabriela; Elster, Nanette R.; Majumder, Mary Anderlik; Palmer, Larry I.; Stone, T. Howard; Hoffman, Richard E. (November 2003). Quarantine and Isolation: Lessons learned from SARS (PDF) (Report). Institute for Bioethics, Health Policy and Law; University of Louisville School of Medicine.

- ^ Nyenswah, Tolbert; Blackley, David J.; Freeman, Tabeh; Lindblade, Kim A.; Arzoaquoi, Samson K.; Mott, Joshua A.; Williams, Justin N.; Halldin, Cara N. et al. (27 February 2015). “Community Quarantine to Interrupt Ebola Virus Transmission — Mawah Village, Bong County, Liberia, August–October, 2014”. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64 (7): 179–182. PMC 5779591. PMID 25719679.

- ^ “Liberian Soldiers Seal Slum to Halt Ebola”. NBC News. (2014年8月20日) 2014年8月23日閲覧。

- ^ MacDougall, Clair; Giahyue, James Harding (2014年8月20日). “Liberia police fire on protesters as West Africa's Ebola toll hits 1,350”. Reuters 2014年8月23日閲覧。

- ^ Paye-Layleh, Jonathan (30 August 2014). “Liberian Ebola survivor calls for quick production of experimental drug”. Associated Press. Global News 30 August 2014閲覧。

- ^ Levenson, Michael (2020年1月22日). “Scale of China's Wuhan Shutdown Is Believed to Be Without Precedent”. The New York Times 2020年1月25日閲覧。

- ^ Rachman, Gideon (28 February 2020). “Coronavirus: how the outbreak is changing global politics”. Financial Times 29 February 2020閲覧。

- ^ Singh, Karan Deep; Goel, Vindu; Kumar, Hari; Gettleman, Jeffrey (2020年3月25日). “India, Day 1: World’s Largest Coronavirus Lockdown Begins” (英語). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 2021年3月13日閲覧。

- ^ Tang, Ashley (16 March 2020). “Malaysia announces movement control order after spike in Covid-19 cases (updated)”. The Star 2021年1月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Coronavirus: Northern Italy quarantines 16 million people”. BBC News. (8 March 2020) 8 March 2020閲覧。

- ^ Sandford, Alasdair (2020年4月2日). “Coronavirus: Half of humanity now on lockdown as 90 countries call for confinement”. Euronews 2021年1月1日閲覧。