MECP2

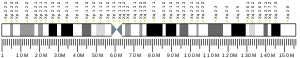

MECP2(methyl-CpG binding protein 2)は、MECP2遺伝子にコードされるタンパク質である[5][6]。MECP2は神経細胞の正常な機能に必要不可欠であるようである。このタンパク質は成熟した神経細胞に高レベルで存在しており、こうした細胞で特に重要な役割を果たしていると考えられている。MECP2はいくつかの遺伝子の抑制(サイレンシング)に関与している可能性が高く、これらの遺伝子にコードされるタンパク質が必要でないときに合成されないようにしている。近年の研究では、MECP2は遺伝子の活性化にも関与していることが示されている[7]。MECP2遺伝子はX染色体長腕のバンド28(Xq28)に位置している。

MECP2はDNAメチル化のリーダー(認識を担う因子)として重要である。メチル化CpG結合ドメイン(MBD)は5-メチルシトシン(5-mC)領域を認識する。MECP2遺伝子はX連鎖遺伝子であり、X染色体の不活性化の影響を受ける。MECP2遺伝子の変異は、進行性の神経発達障害であるレット症候群の大部分の症例の原因となっており、また女性における認知機能障害の最も一般的な原因の1つである[8]。この遺伝子には少なくとも53種類の疾患原因変異が発見されている[9]。

機能

[編集]MECP2タンパク質は体内の全ての細胞に存在しており、脳内では状況に依存して転写のリプレッサーまたはアクチベーターとして機能する。一方で、MECP2がアクチベーターとして機能するという知見はまだ歴史が浅いものであり、いまだ議論がある[10]。脳内では、MECP2は神経細胞に高濃度で存在し、中枢神経系の成熟やシナプス結合の形成過程と関係している[11]。

作用機序

[編集]MECP2はメチル化されたDNAに結合する。MECP2は他のタンパク質と相互作用して複合体を形成し、遺伝子の発現をオフにする。MECP2はシトシン(C)に化学的変化(メチル化)が生じたゲノム領域に選択的に結合する。こうした化学的変化はCpGアイランドと呼ばれる特定のCpG配列に生じる。CpGアイランドは多くの遺伝子に存在しており、遺伝子の開始部位近傍に高頻度で存在している。多くの場合、メチル化が起こっていないときにはMECP2はこうした部位に結合しない。いくつかの遺伝子の発現はCpGアイランドのメチル化を介して調節されており、MECP2はこうした遺伝子の一部の調節に関与している可能性がある。MECP2の具体的な標的遺伝子は未同定であるが、標的遺伝子は中枢神経系の正常な機能に重要な役割を果たしていると考えられている。一方で、神経細胞におけるMECP2結合部位の大規模マッピング研究では、結合部位のうちCpGアイランド内に位置しているものはわずか6%であることが示された。また、MECP2が結合しているプロモーターの約63%は活発に発現しており、高度にメチル化が生じているのはわずか6%であった。このことは、MECP2がメチル化プロモーターのサイレンシング以外の何らかの機能を有していることを示唆している[12]。

結合したMECP2はクロマチン構造を凝縮する、ヒストンデアセチラーゼ(HDAC)と複合体を形成する、もしくは転写因子を直接的に遮断するといった過程によって転写リプレッサーとして機能する。近年の研究では、MECP2は転写因子CREB1のリクルートを介して転写アクチベーターとして機能している可能性も示されている。このことは、MECP2が遺伝子発現において二重の役割を果たしている可能性のある重要な転写調節因子であることを示唆している。実際に、MECP2によって調節される遺伝子の大部分は、抑制ではなく活性化されているようである[13]。しかしながら、MECP2がこれらの遺伝子を直接調節しているのか、それともこうした変化が二次的なものであるのかに関しては議論がある[10]。その後の研究では、いくつかのケースではMECP2が非メチル化DNAに直接結合している可能性も示されている[14]。MECP2は、UBE3AやDLX5といったインプリンティング遺伝子・遺伝子座の調節に関与していることが示唆されている[15]。

マウスMecp2+/-神経幹細胞では、Mecp2の発現の低下によって細胞老化の増大、増殖能の欠陥、未修復のDNA損傷の蓄積が引き起こされる[16]。Mecp2+/-細胞では、DNA損傷試薬による処理後にコントロール細胞よりも多くの損傷DNAが蓄積し、細胞死を起こしやすくなる[16]。Mecp2の発現の低下はDNA修復能の低下を引き起こし、このことが神経機能の低下に寄与している可能性が高い[16]。

構造

[編集]MECP2はメチル化CpG結合ドメインタンパク質(methyl-CpG-binding domain protein、MBD)ファミリーに属するが、他のメンバーとは異なる固有のドメイン構成を有する。MECP2には85アミノ酸からなるMBDと104アミノ酸からなる転写抑制ドメイン(transcriptional repression domain、TRD)という2つの機能ドメインを持つ。MBDはDNA鎖上のメチル化CpG部位に結合するくさび型構造を形成する。その後、TRDがSIN3Aと相互作用し、HDACをリクルートする[17]。また、C末端には反復配列が存在し、この領域はフォークヘッドファミリーとの配列類似性がみられる[18]。

疾患における役割

[編集]MECP2と疾患との関係は、主にレット症候群でみられるMECP2遺伝子の機能喪失(過小発現)、もしくはMECP2重複症候群でみられる機能獲得(過剰発現)のいずれかと関連したものである。多くの変異がMECP2遺伝子の発現喪失と関連しており、レット症候群の患者に同定されている。こうした変異にはMECP2遺伝子の一塩基置換(SNP)、挿入や欠失、そしてタンパク質へのプロセシングに関する遺伝子情報(RNAスプライシング)の変化を伴うものがある。遺伝子の変異はMECP2タンパク質の構造変化、または量の減少をもたらす。その結果、タンパク質はDNAに結合できなくなったり、遺伝子をオン・オフすることができなくなったりする。その結果、通常MECP2によって抑制されている遺伝子がそのタンパク質産物が必要ではない場合にも活性化状態となり、また通常MECP2によって活性化されている他の遺伝子は不活性状態となりその産物は欠乏する。こうした欠陥は神経細胞の正常な機能を妨げ、レット症候群の徴候や症状の原因となる。

レット症候群は主に女児にみられる疾患であり、有病率は約10,000人の女児につき1人である。正常な核型でこの疾患を抱える男児の場合、出生時まで生存することは稀であり、出生した場合にも多くの場合は直後に死亡する。出生後に疾患の徴候を見つけることは非常に困難であるが、6か月から18か月後には言語と運動機能の遅れがみられ、続いてけいれん発作、発育の遅れ、認知・運動機能障害がみられようになる[19]。MECP2遺伝子座はX連鎖しており、疾患の原因となるアレルは優性遺伝する。この疾患が女性に多くみられる原因は男性では致死となるためであると考えられてきたが、患者の大部分は父親由来のX染色体に生じたde novo変異を原因としており、女性だけが変異の生じやすい父親由来のX染色体を受け継ぐためであることを示唆する結果が得られている。そして稀な男性のレット症候群も報告されている[20][21][22]。

MECP2遺伝子の変異は、中枢神経系に影響が及ぶ他の疾患の患者でも同定されている。一例として、MECP2の変異は中等度から重度のX連鎖性精神遅滞と関連している。MECP2遺伝子変異は、幼児期までしか生存することのできない重症脳機能障害(新生児脳症)の男児にも見つかっている。また、レット症候群とアンジェルマン症候群(精神遅滞、運動障害、状況に不適切な笑いや興奮性によって特徴づけられる)の特徴を併せ持つ何人かの患者ではMECP2遺伝子に変異がみられる。自閉症の一部症例でもMECP2の変異または遺伝子活性の変化が報告されている[23]。

全身性エリテマトーデスの患者においても、MECP2遺伝子の遺伝的多型が報告されている[24]。この疾患は複数の器官に影響が及ぶ全身性自己免疫疾患である。MECP2の多型はこれまでヨーロッパ系とアジア系の患者で報告されている。

MECP2の遺伝的喪失は、青斑核の細胞の性質を変化させることが明らかにされている。この領域は大脳皮質と海馬に対してノルアドレナリン作動性神経支配を行っている唯一の領域である。青斑核のニューロンは脳幹や前脳全体に対するノルアドレナリン入力の重要な源であり、呼吸や認知機能などレット症候群で異常が生じる多様な機能の調節に関与していることから、MECP2の喪失による中枢神経系機能不全における重要な部位であることが示唆されている[25]。

相互作用

[編集]MECP2はSKIやNCOR1と相互作用することが示されている[26]。神経細胞では、MECP2のmRNAはmiR-132と相互作用し、タンパク質の発現がサイレンシングされると考えられており、脳内のMECP2濃度を調節する恒常性機構の1つとなっている[27]。

MECP2とホルモン

[編集]発生中のラットの脳において、Mecp2は性的二型性の社会行動の発達を調節している。出生後24時間のラットの脳の扁桃体や視床下部ではMecp2の発現レベルがオスとメスで異なるが、この差異は出生後10日には観察されなくなる。オスはメスよりもMecp2の発現レベルが低く[28]、この時期は新生ラットの脳がステロイド感受性を示す期間と一致している。出生後数日間siRNAによってMecp2の発現レベルを低下させることでオスの幼若ラットの社会的遊び行動(social play behavior)はメスのレベルにまで低下するが、メスでは影響は生じない[29]。

Mecp2は、発生中のラットの扁桃体においてホルモン関連行動の形成や性差に重要な役割を果たしている。オスのラットではMecp2はアルギニンパソプレシン(AVP)やアンドロゲン受容体(AR)の産生を調節しているようであるが、メスではこうした作用はみられない。バソプレシンはつがい形成(pair bonding)[30]やsocial recognition[31]など多くの社会行動を調節していることが知られている。一般的にオスのラットは扁桃体のバソプレシンレベルが高いが[32]、出生後3日間Mecp2の発現レベルを低下させることでこの脳領域のバソプレシンはメスのレベルにまで低下し、成体でもこの効果は持続する。Mecp2の発現レベルをsiRNAによって低下させたオスのラットではARも注入後2週間にわたって有意に減少するが、この効果は成体となるまでには消失する[33]。

幼若期ストレス

[編集]MECP2は幼若期ストレス(early life stress、ELS)への応答を管理しており、ELSは視床下部の室傍核のMECP2タンパク質の高リン酸化と相関している[34]。MECP2のリン酸化の結果、AVP遺伝子のプロモーター領域におけるMECP2の占有率が低下し、AVPの発現レベルが上昇する。バソプレシンは、ストレスへの応答や処理を調節する系である、視床下部-下垂体-副腎系に関与する主要なホルモンである。このように、MECP2タンパク質の機能の低下は、神経のストレス応答をアップレギュレーションする。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000169057 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000031393 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2”. Nat. Genet. 23 (2): 185–8. (October 1999). doi:10.1038/13810. PMID 10508514.

- ^ “Purification, sequence, and cellular localization of a novel chromosomal protein that binds to methylated DNA”. Cell 69 (6): 905–14. (June 1992). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90610-O. PMID 1606614.

- ^ “MECP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription”. Science 320 (5880): 1224–9. (2008). Bibcode: 2008Sci...320.1224C. doi:10.1126/science.1153252. PMC 2443785. PMID 18511691.

- ^ “Entrez Gene: MECP2 methyl CpG binding protein 2 (Rett syndrome)”. 2023年12月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Refinement of evolutionary medicine predictions based on clinical evidence for the manifestations of Mendelian diseases”. Scientific Reports 9 (1): 18577. (December 2019). Bibcode: 2019NatSR...918577S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54976-4. PMC 6901466. PMID 31819097.

- ^ a b “Medicine. Activating a repressor.”. Science 320 (5880): 1172–3. (May 2008). doi:10.1126/science.1159146. PMC 2857976. PMID 18511680.

- ^ “Expression of MeCP2 in postmitotic neurons rescues Rett syndrome in mice”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (16): 6033–8. (April 2004). Bibcode: 2004PNAS..101.6033L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401626101. PMC 395918. PMID 15069197.

- ^ “Integrated epigenomic analyses of neuronal MeCP2 reveal a role for long-range interaction with active genes”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (49): 19416–21. (December 2007). Bibcode: 2007PNAS..10419416Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707442104. PMC 2148304. PMID 18042715.

- ^ “MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription”. Science 320 (5880): 1224–9. (May 2008). Bibcode: 2008Sci...320.1224C. doi:10.1126/science.1153252. PMC 2443785. PMID 18511691.

- ^ “Chromatin compaction by human MeCP2. Assembly of novel secondary chromatin structures in the absence of DNA methylation”. J. Biol. Chem. 278 (34): 32181–8. (August 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M305308200. PMID 12788925.

- ^ LaSalle JM (2007). “The odyssey of MeCP2 and parental imprinting”. Epigenetics 2 (1): 5–10. doi:10.4161/epi.2.1.3697. PMC 1866173. PMID 17486180.

- ^ a b c “Neural stem cells from a mouse model of Rett syndrome are prone to senescence, show reduced capacity to cope with genotoxic stress, and are impaired in the differentiation process”. Exp. Mol. Med. 50 (3): 1. (March 2018). doi:10.1038/s12276-017-0005-x. PMC 6118406. PMID 29563495.

- ^ “The solution structure of the domain from MeCP2 that binds to methylated DNA”. J. Mol. Biol. 291 (5): 1055–65. (September 1999). doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3023. PMID 10518942.

- ^ Paul A. Wade (December 2001). “Methyl CpG-binding proteins and transcriptional repression”. BioEssays 23 (12): 1131–1137. doi:10.1002/bies.10008. PMID 11746232. オリジナルの2007-08-14時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ “MeCP2 in neurons: closing in on the causes of Rett syndrome”. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14 Spec No 1: R19–26. (April 2005). doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi102. PMID 15809268.

- ^ “Multiple pathways regulate MeCP2 expression in normal brain development and exhibit defects in autism-spectrum disorders”. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13 (6): 629–39. (March 2004). doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh063. PMID 14734626.

- ^ Trappe, R.; Laccone, F.; Cobilanschi, J.; Meins, M.; Huppke, P.; Hanefeld, F.; Engel, W. (2001-05). “MECP2 mutations in sporadic cases of Rett syndrome are almost exclusively of paternal origin”. American Journal of Human Genetics 68 (5): 1093–1101. doi:10.1086/320109. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1226090. PMID 11309679.

- ^ Girard, M.; Couvert, P.; Carrié, A.; Tardieu, M.; Chelly, J.; Beldjord, C.; Bienvenu, T. (2001-03). “Parental origin of de novo MECP2 mutations in Rett syndrome”. European journal of human genetics: EJHG 9 (3): 231–236. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200618. ISSN 1018-4813. PMID 11313764.

- ^ Hunt, Katie (12 January 2016). “Chinese scientists create monkeys with autism gene”. CNN News 2016年1月27日閲覧。

- ^ Jin, Dong-Yan, ed (2008). “Common variants within MECP2 confer risk of systemic lupus erythematosus”. PLOS ONE 3 (3): e1727. Bibcode: 2008PLoSO...3.1727S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001727. PMC 2253825. PMID 18320046.

- ^ “Pathophysiology of Locus Ceruleus Neurons in a Mouse Model of Rett Syndrome”. Journal of Neuroscience 29 (39): 12187–12195. (2009). doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3156-09.2009. PMC 2846656. PMID 19793977.

- ^ “The Ski protein family is required for MeCP2-mediated transcriptional repression”. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (36): 34115–21. (September 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M105747200. PMID 11441023.

- ^ “Homeostatic regulation of MeCP2 expression by a CREB-induced microRNA”. Nat. Neurosci. 10 (12): 1513–4. (December 2007). doi:10.1038/nn2010. PMID 17994015.

- ^ “Sex difference in mecp2 expression during a critical period of rat brain development”. Epigenetics 2 (3): 173–8. (September 2007). doi:10.4161/epi.2.3.4841. PMID 17965589.

- ^ “Mecp2 organizes juvenile social behavior in a sex-specific manner”. J. Neurosci. 28 (28): 7137–42. (July 2008). doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1345-08.2008. PMC 2569867. PMID 18614683.

- ^ “A role for central vasopressin in pair bonding in monogamous prairie voles”. Nature 365 (6446): 545–8. (October 1993). Bibcode: 1993Natur.365..545W. doi:10.1038/365545a0. PMID 8413608.

- ^ “Profound impairment in social recognition and reduction in anxiety-like behavior in vasopressin V1a receptor knockout mice”. Neuropsychopharmacology 29 (3): 483–93. (March 2004). doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300360. PMID 14647484.

- ^ “Sexual differentiation of central vasopressin and vasotocin systems in vertebrates: different mechanisms, similar endpoints”. Neuroscience 138 (3): 947–55. (2006). doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.050. PMC 1457099. PMID 16310321.

- ^ “Neonatal MeCP2 is important for the organization of sex differences in vasopressin expression”. Epigenetics 7 (3): 230–8. (March 2012). doi:10.4161/epi.7.3.19265. PMC 3335947. PMID 22430799.

- ^ “Dynamic DNA methylation programs persistent adverse effects of early-life stress”. Nat. Neurosci. 12 (12): 1559–66. (December 2009). doi:10.1038/nn.2436. PMID 19898468.

関連文献

[編集]- “The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology”. Neuron 56 (3): 422–37. (2007). doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. PMID 17988628.

- “Identification of MeCP2 mutations in a series of females with autistic disorder”. Pediatr Neurol 28 (3): 205–11. (2003). doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(02)00624-0. PMID 12770674.

- “Review article: breaking new ground with Rett syndrome”. J Intellect Disabil Res 47 (Pt 8): 580–7. (2003). doi:10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00506.x. PMID 14641805.

- “Rett syndrome: a prototypical neurodevelopmental disorder”. Neuroscientist 10 (2): 118–28. (2004). doi:10.1177/1073858403260995. PMID 15070486.

- “Phenotypic manifestations of MECP2 mutations in classical and atypical Rett syndrome”. Am J Med Genet A 126 (2): 129–40. (2004). doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.20571. PMID 15057977.

- “Mutations in the gene encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 cause Rett syndrome”. Brain Dev 23 (Suppl 1): S147–51. (2001). doi:10.1016/S0387-7604(01)00376-X. PMID 11738862.

- “Rett syndrome and the MECP2 gene”. J Med Genet 38 (4): 217–23. (2001). doi:10.1136/jmg.38.4.217. PMC 1734858. PMID 11283201.

- “Rett syndrome and MeCP2: linking epigenetics and neuronal function.”. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71 (6): 1259–72. (2003). doi:10.1086/345360. PMC 378559. PMID 12442230.

- “Neurodevelopmental disorders in males related to the gene causing Rett syndrome in females (MECP2).”. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 7 (1): 5–12. (2003). doi:10.1016/S1090-3798(02)00134-4. PMID 12615169.

- “Mutations and polymorphisms in the human methyl CpG-binding protein MECP2.”. Hum. Mutat. 22 (2): 107–15. (2004). doi:10.1002/humu.10243. PMID 12872250.

- “Rett syndrome: clinical review and genetic update.”. J. Med. Genet. 42 (1): 1–7. (2006). doi:10.1136/jmg.2004.027730. PMC 1735910. PMID 15635068.

- “Association by guilt: identification of DLX5 as a target for MeCP2 provides a molecular link between genomic imprinting and Rett syndrome.”. BioEssays 27 (7): 676–80. (2005). doi:10.1002/bies.20266. PMID 15954098.

- Zlatanova J (2005). “MeCP2: the chromatin connection and beyond.”. Biochem. Cell Biol. 83 (3): 251–62. doi:10.1139/o05-048. PMID 15959553.

- “MeCP2 expression and function during brain development: implications for Rett syndrome's pathogenesis and clinical evolution.”. Brain Dev. 27 (Suppl 1): S77–S87. (2006). doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2004.10.008. PMID 16182491.

- Armstrong DD (2006). “Can we relate MeCP2 deficiency to the structural and chemical abnormalities in the Rett brain?”. Brain Dev. 27 (Suppl 1): S72–S76. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2004.10.009. PMID 16182497.

- “Chromatin remodeling and neuronal function: exciting links.”. Genes, Brain and Behavior 5 (Suppl 2): 80–91. (2006). doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00227.x. PMID 16681803.

- “Molecular genetics of Rett syndrome: when DNA methylation goes unrecognized.”. Nature Reviews Genetics 7 (6): 415–26. (2006). doi:10.1038/nrg1878. PMID 16708070.

- Francke U (2007). “Mechanisms of disease: neurogenetics of MeCP2 deficiency.”. Nature Clinical Practice Neurology 2 (4): 212–21. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0148. PMID 16932552.

外部リンク

[編集]- International Rett Syndrome Foundation

- Rett UK Support and Research Charity

- Reverse Rett UK

- Rett Registry UK

- Rett Syndrome Research Trust

- GeneCard

- RettBASE: IRSA MECP2 Variation Database

- GeneReview/NIH/UW entry on MECP2-Related Disorders

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on MECP2 Duplication Syndrome

- UK Site for Families Affected by MECP2.

- Site for Families Affected by MECP2.

- Site officiel français sur la duplication MeCP2