RAF1

RAF1はヒトではRAF1遺伝子にコードされる酵素である[4][5][6]。c-Raf(proto-oncogene c-RAF)という名称が用いられることもあり、他にもRAF proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase、Raf-1などとも呼ばれる。c-RafはMAPK/ERK経路(ERK1/2経路)を構成し、Rasサブファミリーの下流のMAPキナーゼキナーゼキナーゼ(MAP3K)として機能する[7]。c-Rafはセリン/スレオニンキナーゼのRafキナーゼファミリーのメンバーであり、TKL(Tyrosine-kinase-like)グループに属する。

発見

[編集]最初のRafキナーゼであるv-Rafは1983年に発見された。3611-MSVと命名されたマウスレトロウイルスから単離され、齧歯類の線維芽細胞をがん細胞株へと形質転換することが示された。そのため、この遺伝子はvirus-induced rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma(v-raf)と名付けられた。1年後、鳥類のレトロウイルスMH2から他の形質転換遺伝子が発見されてv-milと名付けられ、v-rafときわめて類似していることが判明した[8]。研究者らはこれらの遺伝子がセリン/スレオニンキナーゼ活性を持つ酵素をコードしていることを示した[9]。v-Rafとv-Milの正常な細胞性ホモログがマウスとニワトリの双方ですぐに発見され(細胞性(cellular)のRafを意味するc-Rafと名付けられた)、これらも成長や細胞分裂を調節する役割を持つことが明らかとなった[10][11]。現在ではc-Rafは、最初に記載されたMAPK経路であるERK1/2シグナル伝達経路の主要な構成要素であることが知られている[12]。c-RafはMAP3Kとして機能し、キナーゼカスケード全体の開始を担う。その後の実験によって、正常な細胞性のRafの遺伝子も変異によって、MEK1/2やERK1/2の活性を過剰に駆動するがん遺伝子となることが示された。脊椎動物のゲノムにはRafの遺伝子が複数含まれている。c-Rafの発見の数年後、2つの関連するキナーゼ、A-RafとB-Rafが記載された。ヒトの腫瘍の多くでB-Rafの遺伝子に発がん性をもたらす「ドライバー」変異が生じていることが判明し、近年B-Rafに研究の焦点が当てられている[13]。こうした変異は、制御を受けない高活性のRaf酵素を誘導する。Rafキナーゼに対する診断・治療標的としての関心は近年新たなピークに達している[14]。

構造

[編集]ヒトのc-Rafの遺伝子RAF1は3番染色体上に位置している。少なくとも2種類のアイソフォーム(選択的エクソンの組み込みまたは除去によるもの)が記載されているが、両者にはわずかな差異しか存在しない。主要な短いアイソフォームのmRNAは17個のエクソンから構成され、648アミノ酸からなるプロテインキナーゼをコードする[15]。

他の多くのMAP3Kと同様、c-Rafは複数のドメインから構成されるタンパク質で、触媒活性の調節を補助する複数の付加的なドメインが存在する。N末端領域には、Ras結合ドメイン(RBD)とCキナーゼ相同ドメイン1(C1ドメイン)が隣接して存在する。双方の保存されたドメイン構造がこれまでに解かれており、それらによる調節機構が解明されている。

RBDはユビキチン様フォールドを持ち(これは他の低分子量Gタンパク質結合ドメインの多くと同様である)、GTP結合型のRasタンパク質のみを選択的に結合する[16][17][18]。

C1ドメインはRBDの直後に存在し、システインに富み、2つの亜鉛イオンによって安定化される特別なジンクフィンガーである。プロテインキナーゼC(PKC)のジアシルグリセロール結合C1ドメインに類似しているが[19][20]、PKCとは異なり、RafファミリーキナーゼのC1ドメインはジアシルグリセロールを結合しない[21]。代わりに、セラミド[21]、ホスファチジン酸[22]などの他の脂質と相互作用し、活性化されたGTP結合型Rasの認識の補助も行う[20][23]。

これら2つのドメインがきわめて近接して存在していることや、いくつかの実験的データからは、これらは直接的な物理的相互作用を行うことでキナーゼドメインの活性を負に調節する単一のユニットとして機能することが示唆されている[24]。歴史的に、この自己阻害ブロックはCR1(Conserved Region 1)と呼ばれており、ヒンジ領域はCR2、キナーゼドメインはCR3と呼ばれていた。自己阻害状態のキナーゼの正確な構造はまだ明らかではない。

自己阻害ブロックとキナーゼドメインの間には、すべてのRafタンパク質に特有の長いフラグメントが存在する。このフラグメントはセリンに富むものの、関連するRafの間での配列の保存性は低い。この領域は構造を持たず、非常に柔軟性が高いようである。この領域の役割として最も可能性が高いのは、堅く折りたたまれた自己阻害ドメインと触媒ドメインとの間の「ヒンジ」としての機能であり、分子内の複雑な動きや大きなコンフォメーション変化を可能にしていると考えられている[25]。このヒンジ領域には、14-3-3タンパク質の認識を担う、小さな保存された領域(short linear motif)が含まれるが、認識が行われるのは重要なセリン残基(ヒトのc-Rafではセリン259番残基(Ser259))がリン酸化されているときのみである。同様のモチーフはすべてのRafのC末端付近(キナーゼドメインよりも下流、リン酸化されるSer621を中心とする領域)にも存在する。

c-RafのC末端側の半分は単一のドメインへと折りたたまれ、触媒活性を担う。このキナーゼドメインの構造は、c-Raf[26]とB-Raf[27]の双方で詳細に解明されている。このドメインは他のRafキナーゼやKSR(kinase suppressor of Ras)タンパク質ときわめて類似しており、MLK(mixed lineage kinase)ファミリーなど、他のMAP3Kの一部とも明らかに類似している。これらはプロテインキナーゼのTKL(tyrosine kinase like)グループを構成する。これらの触媒ドメインの特徴の一部はチロシンキナーゼとも共通であるが、TKLグループのキナーゼの活性は標的タンパク質のセリンとスレオニン残基のリン酸化に限定されている。Rafキナーゼの最も重要な基質は(自身を除くと)MEK1とMEK2キナーゼであり、これらキナーゼの活性はRafによるリン酸化に厳密に依存している。

進化的関係

[編集]ヒトのc-Rafが属するRafキナーゼファミリーには他にB-RafとA-Rafの2つのメンバーが存在し、これらは大部分の脊椎動物に存在する。保存されていないN末端とC末端領域の長さが異なる点を除いて、これらには共通したドメイン構成、構造、調節機構がみられる。c-RafとB-Rafに関しては比較的研究が進んでいるのに対し、A-Rafの正確な機能には不明点が多いが、類似した機能を持つと考えられている。これらをコードする遺伝子は、脊椎動物の進化の初期に起こった遺伝子またはゲノムの重複の結果、単一の祖先型Raf遺伝子から生じたと考えられている。他の動物の多くはRafを1つしか持ち合わせていない。ショウジョウバエDrosophilaではPhlまたはDrafと呼ばれており[28]、線虫Caenorhabditis elegansではLin-45と呼ばれている[29]。

また多細胞動物にはRafと密接に関連した、KSR(Kinase Suppressor of Ras)と呼ばれるキナーゼが存在する。哺乳類などの脊椎動物には、KSR1、KSR2という2つのパラログが存在する。C末端のキナーゼドメインはRafと非常に類似しているが(この領域はもともとKSRではCA5、RafではCR3と呼ばれていた)、N末端の調節領域は異なる。KSRにも柔軟なヒンジ領域(CA4)とC1ドメイン(CA3)が存在するが、Ras結合ドメインは全く存在しない。代わりにKSRには、CA1、CA2と名付けられた特有の調節領域がN末端に存在する。長らくCA1ドメインの構造は不明であったが、2012年にKSR1のCA1領域の構造が解かれ、コイルドコイルが付加されたSAM(Sterile alpha motif)ドメイン(CC-SAM)構造であることが明らかにされた。この領域はKSRの膜結合を補助していると考えられている[30]。Rafと同様、KSRにもリン酸化依存的な14-3-3結合モチーフが2つ存在するが、KSRのヒンジ領域にはさらにMAPK結合モチーフが存在する。このモチーフの典型的な配列はPhe-x-Phe-Pro(FxFP)であり、ERK1/2経路におけるRafキナーゼのフィードバック調節に重要である。これまで知られているところによると、KSRはRafと同じ経路に関与するが、副次的な役割しか持たない。KSRの内在的なキナーゼ活性は極めて弱いため、近年になってようやく活性が実証されるまで長らく不活性な因子であると考えられていた[31][32]。しかしKSRのキナーゼ活性はMEK1やMEK2のリン酸化には無視できるほどの寄与しかしていない。KSRの主要な役割はRafのヘテロ二量体化のパートナーとなることであるようで、アロステリック機構によってRafの活性化を大きく促進する。同様の現象は他のMAP3Kに関しても記載されている。例えば、ASK2はそれ自身では活性の弱い酵素であるが、ASK1とのヘテロ二量体として活性を持つ[33]。

活性の調節

[編集]

c-Rafの活性の調節は複雑である。c-RafはERK1/2経路の「ゲートキーパー」としての役割を持ち、その活性化は多数の阻害機構によって阻止され、通常は一段階で活性化されることはない。最も重要な調節機構は、N末端の自己阻害ブロックとキナーゼドメインとの直接的な物理的相互作用である。その結果、触媒部位が閉じられ、キナーゼ活性は完全に停止する[24]。この「閉じた」状態は、Rafの自己阻害ドメインがキナーゼドメインと競合するパートナー(最も重要なものはGTP結合型のRas)と結合したときにのみ解除される。活性化された低分子量Gタンパク質はc-Rafの分子内相互作用を解除し、その結果としてc-Rafにはコンフォメーション変化が起こり、キナーゼの活性化と基質の結合に必要な「開いた」状態となる[36]。

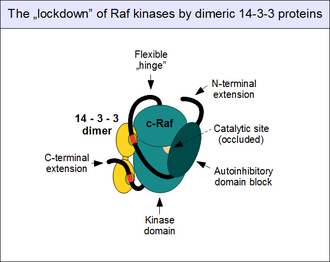

14-3-3タンパク質も自己阻害に寄与する。14-3-3は常に二量体を形成していることが知られており、二量体には2つの結合部位が存在する[37]。二量体は「手錠」のように機能し、結合パートナーを一定の距離と配向に固定する。c-Rafの2つの14-3-3結合モチーフが正確に配置され、そこへ1つの14-3-3タンパク質二量体(14-3-3ζなど)が結合した場合、c-Rafは自己阻害を促進し、自己阻害ドメインと触媒ドメインの解離を許容しないコンフォメーションへと固定される[38]。このc-Rafの固定(他のRafやKSRでも起こる)は、14-3-3結合モチーフのリン酸化によって制御されている。リン酸化されていない14-3-3結合モチーフにはパートナーは結合せず、他のプロテインキナーゼによって保存されたセリン(Ser259とSer621)がリン酸化されている必要がある。このイベントへの関与が示唆されている最も重要なキナーゼはTAK1(TGF-β activated kinase 1)であり、リン酸基の除去を行う酵素はプロテインホスファターゼ1とプロテインホスファターゼ2A複合体である[39][40]。

Rafへの14-3-3の結合は必ずしも阻害的に働くわけではないことには注意が必要である。いったんRafが開いた構造となって二量体化すると、14-3-3は2つのキナーゼの間を橋渡しするようにトランスに結合し、二量体を離すためではなく、結合を強化するための「手錠」として機能する[41]。c-Rafと14-3-3の結合にはさらに他の様式も存在するが、それらの役割はあまり解明されていない[42]。

二量体化もc-Rafの活性の調節に重要な機構であり、Rafの活性化ループのリン酸化に必要である。通常は、「開いた」構造のキナーゼドメインのみが二量体化を行う。c-Rafのホモ二量体も他の因子とのヘテロ二量体も同様な振る舞いを示す[32]。

c-Rafが十分な活性を持ち、活性化状態が安定化されるためには、さらにc-Rafの活性化ループのリン酸化が必要である。現在のところ、この役割を果たすことが知られている唯一のキナーゼはRafファミリーキナーゼ自身である。しかし、PAK1など他の一部のキナーゼもc-Rafのキナーゼドメイン近傍の他の残基をリン酸化することができる。これらの副次的なキナーゼの正確な役割は未知である。c-Rafの場合、活性化ループの「トランスリン酸化」にはc-RafとKSR1の双方が必要である。二量体は背中合わせに結合した構造をしているため、このリン酸化はトランスにのみ起こる(ある二量体が他の二量体のリン酸化行い、4つのメンバーからなる一過的複合体が形成される)[43]。キナーゼドメインの保存されたアルギニン残基とリジン残基との相互作用によって、リン酸化された活性化ループはコンフォメーションのシフトが起こってしっかりとした構造をとるようになり、脱リン酸化が起こるまでキナーゼドメインを完全に活性化された状態に固定する。また、リン酸化された活性化ループによってキナーゼは自己阻害ドメインの存在に対して非感受性となる[44]。KSRの活性化ループにはリン酸化残基が存在しないため、この最終段階は起こらない。いったんc-Rafが完全に活性化されるとそれ以上の活性化は必要なく、活性化されたRafは自身の基質と結合できるようになる[45]。大部分のプロテインキナーゼと同様に、c-Rafは複数の基質を持っている。BAD[46]、アデニル酸シクラーゼのいくつか[47]、ミオシン軽鎖ホスファターゼ(MYPT)[48]、心筋トロポニンT(TnTc)[49]などがc-Rafによって直接リン酸化される。Rbタンパク質やCdc25ホスファターゼも基質である可能性が示唆されている[50]。

全てのRaf型酵素の最も重要な標的は、MEK1とMEK2である。c-RafとMEK1の酵素-基質複合体の構造は未解明であるが、KSR2-MEK1複合体の構造から正確なモデリングを行うことが可能である[32]。この複合体では実際には触媒は行われないが、Rafの基質への結合様式はきわめて類似していると考えられている。主要な相互作用面は両者のキナーゼドメインのC末端ローブによってもたらされ、MEK1とMEK2に特有の大きく、ディスオーダーしたプロリンに富むループもRaf(とKSR)の配置に重要な役割を果たす[51]。MEKはRafへの結合に伴って活性化ループの少なくとも2か所がリン酸化され、これによってMEKは活性化される。このキナーゼカスケードの標的はERK1とERK2であり、MEK1またはMEK2によって選択的に活性化される。ERKは細胞内に無数の基質を持ち、転写因子を活性化するために核内へ移行させることもできる。活性化されたERKは細胞生理の多能的なエフェクターであり、細胞分裂サイクル、細胞移動、アポトーシスの阻害、細胞分化に関与する遺伝子の発現制御に重要な役割を果たす。

関係するヒトの疾患

[編集]c-Rafの遺伝的な機能獲得型変異は、稀であるが重篤な症候群のいくつかに関与している。こうした変異の大部分は、2つの14-3-3結合モチーフのうちの1つに1か所のアミノ酸置換が生じているものである[52][53]。c-Rafの変異はヌーナン症候群の原因の1つであると考えられている。ヌーナン症候群の患者は先天性心疾患、低身長や他の奇形がみられる。c-Rafの同様の変異は、関連疾患であるLEOPARD症候群と呼ばれる複雑な欠陥がみられる疾患の原因ともなる。

がんにおける役割

[編集]c-Rafは実験的条件下では明らかにがん遺伝子へ変異する能力を持ち、ヒトの少数の腫瘍でもがん遺伝子への変異がみられるが[54][55]、ヒトの発がんにおいて実際に主要な役割を果たしているのは姉妹キナーゼのB-Rafである[56]。

B-Rafの変異

[編集]調査されたすべてのヒト腫瘍試料の約20%でB-Rafの遺伝子に変異がみられる[57]。これらの変異の圧倒的多数はV600Eの1アミノ酸置換を伴うもので、この異常な遺伝子産物(BRAF-V600E)は臨床分子診断において免疫組織染色によって可視化することができる[58][59]。この置換は活性化ループのリン酸化を模倣するものであり、正常な活性化制御段階の全てを飛び越えて、即座にキナーゼドメインを完全に活性化された状態にする[60]。B-Rafはホモ二量体化によって自身を、そしてヘテロ二量体化によってc-Rafを活性化することができるため、この変異はERK1/2経路を恒常的に活性化して無制御な細胞分裂を駆動し、壊滅的な影響を与える[61]。

治療標的として

[編集]RasとB-Rafの変異はどちらも腫瘍形成に重要であるため、特にV600E変異を有するB-Rafを標的としたいくつかのRaf阻害剤ががんに対する治療薬として開発されている。ソラフェニブは臨床的に有用な最初の薬剤であり、腎細胞がんや悪性黒色腫など、それまでほとんど治療不能であった悪性腫瘍に対して薬理学的な代替手段をもたらした[62]。ベムラフェニブ、レゴラフェニブ、ダブラフェニブなど、いくつかの分子が続いて開発されている。

ATP競合型のB-Raf阻害剤は、K-Ras依存的ながんに望ましくない影響を与える可能性がある。これらはB-Rafの変異が主要因である場合にはB-Rafの活性を完全に阻害するが、それとともにB-Raf自身のホモ二量体化やc-Rafとのヘテロ二量体化も促進する。そのためRafの遺伝子には変異が存在せず、Rafの共通の上流活性化因子であるK-Rasに変異が生じている場合には、c-Rafを阻害するのではなく活性を高めることとなる[26]。この「逆説的」なc-Rafの活性化が起こる可能性があるため、B-Raf阻害剤による治療を始める前には遺伝子診断によって患者のB-Rafの変異のスクリーニングを行う必要がある[63]。

相互作用

[編集]RAF1は次に挙げる因子と相互作用することが示されている。

- AKT1[64]

- ASK1[65]

- BAG1[66]

- BRAF[67]

- Bcl-2[68]

- CDC25A[69][70]

- CFLAR[71]

- FYN[72]

- GRB10[73][74]

- HRAS[75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91]

- HSP90AA1[92][93]

- KRAS[80][81]

- MAP2K1[94]

- MAP3K1[95]

- MAPK7[96]

- MAPK8IP3[97][98]

- PAK1[99]

- PEBP1[94]

- PHB[100]

- PRKCZ[101]

- RAP1A[16][85][102][103]

- RHEB[104][105][106]

- RRAS2[80][107]

- RB1[100][108]

- RBL2[108]

- SHOC2[80]

- STUB1[92]

- SRC[72]

- TSC22D3[109]

- YWHAB[79][101][110][111][112][113]

- YWHAE[112][113]

- YWHAG[101][114][115]

- YWHAH[101][112][116]

- YWHAQ[94][101][114][117]

- YWHAZ[101][118][119][120][121]

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000000441 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Raf-1: a kinase currently without a cause but not lacking in effects”. Cell 64 (3): 479–82. (February 1991). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90228-Q. PMID 1846778.

- ^ “Structure and biological activity of v-raf, a unique oncogene transduced by a retrovirus”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80 (14): 4218–22. (July 1983). Bibcode: 1983PNAS...80.4218R. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.14.4218. PMC 384008. PMID 6308607.

- ^ “The human homologs of the raf (mil) oncogene are located on human chromosomes 3 and 4”. Science 223 (4631): 71–4. (January 1984). Bibcode: 1984Sci...223...71B. doi:10.1126/science.6691137. PMID 6691137.

- ^ “Entrez Gene: RAF1 v-raf-1 murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1”. 2020年4月9日閲覧。

- ^ “Nucleotide sequence of avian retroviral oncogene v-mil: homologue of murine retroviral oncogene v-raf”. Nature 309 (5963): 85–8. (1984). Bibcode: 1984Natur.309...85S. doi:10.1038/309085a0. PMID 6325930.

- ^ “Serine- and threonine-specific protein kinase activities of purified gag-mil and gag-raf proteins”. Nature 312 (5994): 558–61. (1984). Bibcode: 1984Natur.312..558M. doi:10.1038/312558a0. PMID 6438534.

- ^ “Raf-1 protein kinase is required for growth of induced NIH/3T3 cells”. Nature 349 (6308): 426–8. (January 1991). Bibcode: 1991Natur.349..426K. doi:10.1038/349426a0. PMID 1992343.

- ^ “Primary structure of v-raf: relatedness to the src family of oncogenes”. Science 224 (4646): 285–9. (April 1984). Bibcode: 1984Sci...224..285M. doi:10.1126/science.6324342. PMID 6324342.

- ^ “Raf-1 activates MAP kinase-kinase”. Nature 358 (6385): 417–21. (July 1992). Bibcode: 1992Natur.358..417K. doi:10.1038/358417a0. PMID 1322500.

- ^ “Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer”. Nature 417 (6892): 949–54. (June 2002). doi:10.1038/nature00766. PMID 12068308.

- ^ “Raf kinase as a target for anticancer therapeutics”. Mol. Cancer Ther. 4 (4): 677–85. (April 2005). doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0297. PMID 15827342.

- ^ “An alternatively spliced c-mil/raf mRNA is predominantly expressed in chicken muscular tissues and conserved among vertebrate species”. Oncogene 6 (8): 1307–11. (August 1991). PMID 1886707.

- ^ a b “The 2.2 A crystal structure of the Ras-binding domain of the serine/threonine kinase c-Raf1 in complex with Rap1A and a GTP analogue”. Nature 375 (6532): 554–60. (June 1995). Bibcode: 1995Natur.375..554N. doi:10.1038/375554a0. PMID 7791872.

- ^ “Solution structure of the Ras-binding domain of c-Raf-1 and identification of its Ras interaction surface”. Biochemistry 34 (21): 6911–8. (May 1995). doi:10.1021/bi00021a001. PMID 7766599.

- ^ “Complexes of Ras.GTP with Raf-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase”. Science 260 (5114): 1658–61. (June 1993). Bibcode: 1993Sci...260.1658M. doi:10.1126/science.8503013. PMID 8503013.

- ^ “The solution structure of the Raf-1 cysteine-rich domain: a novel ras and phospholipid binding site”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (16): 8312–7. (August 1996). Bibcode: 1996PNAS...93.8312M. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.16.8312. PMC 38667. PMID 8710867.

- ^ a b “The RafC1 cysteine-rich domain contains multiple distinct regulatory epitopes which control Ras-dependent Raf activation”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 (11): 6698–710. (November 1998). doi:10.1128/mcb.18.11.6698. PMC 109253. PMID 9774683.

- ^ a b “A ceramide-binding C1 domain mediates kinase suppressor of ras membrane translocation”. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 24 (3–4): 219–30. (2009). doi:10.1159/000233248. PMC 2978518. PMID 19710537.

- ^ “Role of phosphatidic acid in the coupling of the ERK cascade”. J. Biol. Chem. 283 (52): 36636–45. (December 2008). doi:10.1074/jbc.M804633200. PMC 2606017. PMID 18952605.

- ^ “Two distinct Raf domains mediate interaction with Ras”. J. Biol. Chem. 270 (17): 9809–12. (April 1995). doi:10.1074/jbc.270.17.9809. PMID 7730360.

- ^ a b “Autoregulation of the Raf-1 serine/threonine kinase”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (16): 9214–9. (August 1998). Bibcode: 1998PNAS...95.9214C. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.16.9214. PMC 21318. PMID 9689060.

- ^ “Differential regulation of B-raf isoforms by phosphorylation and autoinhibitory mechanisms”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27 (1): 31–43. (January 2007). doi:10.1128/MCB.01265-06. PMC 1800654. PMID 17074813.

- ^ a b “RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth”. Nature 464 (7287): 431–5. (March 2010). Bibcode: 2010Natur.464..431H. doi:10.1038/nature08833. PMID 20130576.

- ^ “Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF”. Cell 116 (6): 855–67. (March 2004). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00215-6. PMID 15035987.

- ^ “Drosophila melanogaster homologs of the raf oncogene”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7 (6): 2134–40. (June 1987). doi:10.1128/mcb.7.6.2134. PMC 365335. PMID 3037346.

- ^ “Mechanisms of regulating the Raf kinase family”. Cell. Signal. 15 (5): 463–9. (May 2003). doi:10.1016/S0898-6568(02)00139-0. PMID 12639709.

- ^ “A CC-SAM, for coiled coil-sterile α motif, domain targets the scaffold KSR-1 to specific sites in the plasma membrane”. Sci Signal 5 (255): ra94. (December 2012). doi:10.1126/scisignal.2003289. PMC 3740349. PMID 23250398.

- ^ “Mutation that blocks ATP binding creates a pseudokinase stabilizing the scaffolding function of kinase suppressor of Ras, CRAF and BRAF”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (15): 6067–72. (April 2011). Bibcode: 2011PNAS..108.6067H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1102554108. PMC 3076888. PMID 21441104.

- ^ a b c “A Raf-induced allosteric transition of KSR stimulates phosphorylation of MEK”. Nature 472 (7343): 366–9. (April 2011). Bibcode: 2011Natur.472..366B. doi:10.1038/nature09860. PMID 21441910.

- ^ “Heteromeric complex formation of ASK2 and ASK1 regulates stress-induced signaling”. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 362 (2): 454–9. (October 2007). doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.006. PMID 17714688.

- ^ a b “Raf family kinases: old dogs have learned new tricks”. Genes Cancer 2 (3): 232–60. (2011). doi:10.1177/1947601911407323. PMC 3128629. PMID 21779496.

- ^ a b “Scaffolds are 'active' regulators of signaling modules”. FEBS J. 277 (21): 4376–82. (2010). doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07867.x. PMID 20883493.

- ^ “Ras binding opens c-Raf to expose the docking site for mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase”. EMBO Rep. 6 (3): 251–5. (March 2005). doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400349. PMC 1299259. PMID 15711535.

- ^ “Crystal structure of the zeta isoform of the 14-3-3 protein”. Nature 376 (6536): 191–4. (July 1995). Bibcode: 1995Natur.376..191L. doi:10.1038/376191a0. PMID 7603574.

- ^ “Regulation of RAF activity by 14-3-3 proteins: RAF kinases associate functionally with both homo- and heterodimeric forms of 14-3-3 proteins”. J. Biol. Chem. 284 (5): 3183–94. (January 2009). doi:10.1074/jbc.M804795200. PMID 19049963.

- ^ “A phosphatase holoenzyme comprised of Shoc2/Sur8 and the catalytic subunit of PP1 functions as an M-Ras effector to modulate Raf activity”. Mol. Cell 22 (2): 217–30. (April 2006). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.027. PMID 16630891.

- ^ “Protein phosphatases 1 and 2A promote Raf-1 activation by regulating 14-3-3 interactions”. Oncogene 20 (30): 3949–58. (July 2001). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204526. PMID 11494123.

- ^ “A dimeric 14-3-3 protein is an essential cofactor for Raf kinase activity”. Nature 394 (6688): 88–92. (July 1998). Bibcode: 1998Natur.394...88T. doi:10.1038/27938. PMID 9665134.

- ^ “Synergistic binding of the phosphorylated S233- and S259-binding sites of C-RAF to one 14-3-3ζ dimer”. J. Mol. Biol. 423 (4): 486–95. (November 2012). doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2012.08.009. PMID 22922483.

- ^ “Complexity in KSR function revealed by Raf inhibitor and KSR structure studies”. Small GTPases 2 (5): 276–281. (2011). doi:10.4161/sgtp.2.5.17740. PMC 3265819. PMID 22292131.

- ^ “Regulation of Raf through phosphorylation and N terminus-C terminus interaction”. J. Biol. Chem. 278 (38): 36269–76. (September 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M212803200. PMID 12865432.

- ^ “Biochemistry. KSR plays CRAF-ty”. Science 332 (6033): 1043–4. (May 2011). Bibcode: 2011Sci...332.1043S. doi:10.1126/science.1208063. PMID 21617065.

- ^ Bauer, Joseph Alan, ed (2011). “p21-Activated kinase 1 (Pak1) phosphorylates BAD directly at serine 111 in vitro and indirectly through Raf-1 at serine 112”. PLoS ONE 6 (11): e27637. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...627637Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027637. PMC 3214075. PMID 22096607.

- ^ “Raf kinase activation of adenylyl cyclases: isoform-selective regulation”. Mol. Pharmacol. 66 (4): 921–8. (October 2004). doi:10.1124/mol.66.4.921. PMID 15385642.

- ^ “Phosphorylation of the myosin-binding subunit of myosin phosphatase by Raf-1 and inhibition of phosphatase activity”. J. Biol. Chem. 277 (4): 3053–9. (January 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.M106343200. PMID 11719507.

- ^ “Raf-1: a novel cardiac troponin T kinase”. J. Muscle Res. Cell. Motil. 30 (1–2): 67–72. (2009). doi:10.1007/s10974-009-9176-y. PMC 2893395. PMID 19381846.

- ^ “Extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK)/mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK)-independent functions of Raf kinases”. J. Cell Sci. 115 (Pt 8): 1575–81. (April 2002). PMID 11950876.

- ^ “A proline-rich sequence unique to MEK1 and MEK2 is required for raf binding and regulates MEK function”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 (10): 5214–25. (October 1995). doi:10.1128/mcb.15.10.5214. PMC 230769. PMID 7565670.

- ^ “Gain-of-function RAF1 mutations cause Noonan and LEOPARD syndromes with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy”. Nat. Genet. 39 (8): 1007–12. (August 2007). doi:10.1038/ng2073. PMID 17603483.

- ^ “Impaired binding of 14-3-3 to C-RAF in Noonan syndrome suggests new approaches in diseases with increased Ras signaling”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30 (19): 4698–711. (October 2010). doi:10.1128/MCB.01636-09. PMC 2950525. PMID 20679480.

- ^ “Oncogene activation: c-raf-1 gene mutations in experimental and naturally occurring tumors”. Toxicol. Lett. 67 (1–3): 201–10. (April 1993). doi:10.1016/0378-4274(93)90056-4. PMID 8451761.

- ^ “Two transforming C-RAF germ-line mutations identified in patients with therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia”. Cancer Res. 66 (7): 3401–8. (April 2006). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0115. PMID 16585161.

- ^ “Mutations of C-RAF are rare in human cancer because C-RAF has a low basal kinase activity compared with B-RAF”. Cancer Res. 65 (21): 9719–26. (November 2005). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1683. PMID 16266992.

- ^ “COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer”. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 (Database issue): D945–50. (January 2011). doi:10.1093/nar/gkq929. PMC 3013785. PMID 20952405.

- ^ “Immunohistochemical testing of BRAF V600E status in 1,120 tumor tissue samples of patients with brain metastases”. Acta Neuropathol. 123 (2): 223–33. (2012). doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0887-y. PMID 22012135.

- ^ “Assessment of BRAF V600E mutation status by immunohistochemistry with a mutation-specific monoclonal antibody”. Acta Neuropathol. 122 (1): 11–9. (2011). doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0841-z. PMID 21638088.

- ^ “B-Raf and Raf-1 are regulated by distinct autoregulatory mechanisms”. J. Biol. Chem. 280 (16): 16244–53. (April 2005). doi:10.1074/jbc.M501185200. PMID 15710605.

- ^ “Wild-type and mutant B-RAF activate C-RAF through distinct mechanisms involving heterodimerization”. Mol. Cell 20 (6): 963–9. (December 2005). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.022. PMID 16364920.

- ^ “Raf kinases in cancer-roles and therapeutic opportunities”. Oncogene 30 (32): 3477–88. (August 2011). doi:10.1038/onc.2011.160. PMID 21577205.

- ^ “Novel small molecule Raf kinase inhibitors for targeted cancer therapeutics”. Arch. Pharm. Res. 35 (4): 605–15. (March 2012). doi:10.1007/s12272-012-0403-5. PMID 22553052.

- ^ “Phosphorylation and regulation of Raf by Akt (protein kinase B)”. Science 286 (5445): 1741–4. (November 1999). doi:10.1126/science.286.5445.1741. PMID 10576742.

- ^ “Raf-1 promotes cell survival by antagonizing apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 through a MEK-ERK independent mechanism”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (14): 7783–8. (July 2001). Bibcode: 2001PNAS...98.7783C. doi:10.1073/pnas.141224398. PMC 35419. PMID 11427728.

- ^ “Bcl-2 interacting protein, BAG-1, binds to and activates the kinase Raf-1”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (14): 7063–8. (July 1996). Bibcode: 1996PNAS...93.7063W. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.14.7063. PMC 38936. PMID 8692945.

- ^ “Active Ras induces heterodimerization of cRaf and BRaf”. Cancer Res. 61 (9): 3595–8. (May 2001). PMID 11325826.

- ^ “Bcl-2 targets the protein kinase Raf-1 to mitochondria”. Cell 87 (4): 629–38. (November 1996). doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81383-5. PMID 8929532.

- ^ “Raf1 interaction with Cdc25 phosphatase ties mitogenic signal transduction to cell cycle activation”. Genes Dev. 9 (9): 1046–58. (May 1995). doi:10.1101/gad.9.9.1046. PMID 7744247.

- ^ “Activation of CDC 25 phosphatase and CDC 2 kinase involved in GL331-induced apoptosis”. Cancer Res. 57 (14): 2974–8. (July 1997). PMID 9230211.

- ^ “The caspase-8 inhibitor FLIP promotes activation of NF-kappaB and Erk signaling pathways”. Curr. Biol. 10 (11): 640–8. (June 2000). doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00512-1. PMID 10837247.

- ^ a b “Raf-1 interacts with Fyn and Src in a non-phosphotyrosine-dependent manner”. J. Biol. Chem. 269 (26): 17749–55. (July 1994). PMID 7517401.

- ^ “Localization of endogenous Grb10 to the mitochondria and its interaction with the mitochondrial-associated Raf-1 pool”. J. Biol. Chem. 274 (50): 35719–24. (December 1999). doi:10.1074/jbc.274.50.35719. PMID 10585452.

- ^ “Interaction of the Grb10 adapter protein with the Raf1 and MEK1 kinases”. J. Biol. Chem. 273 (17): 10475–84. (April 1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.17.10475. PMID 9553107.

- ^ “Interaction of activated Ras with Raf-1 alone may be sufficient for transformation of rat2 cells”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 (6): 3047–55. (June 1997). doi:10.1128/MCB.17.6.3047. PMC 232157. PMID 9154803.

- ^ “SIAH-1 interacts with CtIP and promotes its degradation by the proteasome pathway”. Oncogene 22 (55): 8845–51. (December 2003). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206994. PMID 14654780.

- ^ “Identification and characterization of rain, a novel Ras-interacting protein with a unique subcellular localization”. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (21): 22353–61. (May 2004). doi:10.1074/jbc.M312867200. PMID 15031288.

- ^ “The small GTP-binding protein, Rhes, regulates signal transduction from G protein-coupled receptors”. Oncogene 23 (2): 559–68. (January 2004). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207161. PMID 14724584.

- ^ a b “Novel raf kinase protein-protein interactions found by an exhaustive yeast two-hybrid analysis”. Genomics 81 (2): 112–25. (February 2003). doi:10.1016/s0888-7543(02)00008-3. PMID 12620389.

- ^ a b c d “The leucine-rich repeat protein SUR-8 enhances MAP kinase activation and forms a complex with Ras and Raf”. Genes Dev. 14 (8): 895–900. (April 2000). PMC 316541. PMID 10783161.

- ^ a b “Stimulation of Ras guanine nucleotide exchange activity of Ras-GRF1/CDC25(Mm) upon tyrosine phosphorylation by the Cdc42-regulated kinase ACK1”. J. Biol. Chem. 275 (38): 29788–93. (September 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.M001378200. PMID 10882715.

- ^ “Identification of a specific effector of the small GTP-binding protein Rap2”. Eur. J. Biochem. 252 (2): 290–8. (March 1998). doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520290.x. PMID 9523700.

- ^ “The junctional multidomain protein AF-6 is a binding partner of the Rap1A GTPase and associates with the actin cytoskeletal regulator profilin”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (16): 9064–9. (August 2000). Bibcode: 2000PNAS...97.9064B. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.16.9064. PMC 16822. PMID 10922060.

- ^ “Rheb inhibits C-raf activity and B-raf/C-raf heterodimerization”. J. Biol. Chem. 281 (35): 25447–56. (September 2006). doi:10.1074/jbc.M605273200. PMID 16803888.

- ^ a b “A human protein selected for interference with Ras function interacts directly with Ras and competes with Raf1”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 (3): 1318–23. (March 1995). doi:10.1128/mcb.15.3.1318. PMC 230355. PMID 7862125.

- ^ “RAS and RAF-1 form a signalling complex with MEK-1 but not MEK-2”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14 (12): 8212–8. (December 1994). doi:10.1128/mcb.14.12.8212. PMC 359360. PMID 7969158.

- ^ “Aiolos transcription factor controls cell death in T cells by regulating Bcl-2 expression and its cellular localization”. EMBO J. 18 (12): 3419–30. (June 1999). doi:10.1093/emboj/18.12.3419. PMC 1171421. PMID 10369681.

- ^ “Identification of neurofibromin mutants that exhibit allele specificity or increased Ras affinity resulting in suppression of activated ras alleles”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16 (5): 2496–503. (May 1996). doi:10.1128/mcb.16.5.2496. PMC 231238. PMID 8628317.

- ^ “Cysteine-rich region of Raf-1 interacts with activator domain of post-translationally modified Ha-Ras”. J. Biol. Chem. 270 (51): 30274–7. (December 1995). doi:10.1074/jbc.270.51.30274. PMID 8530446.

- ^ “Role of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase in cell transformation and control of the actin cytoskeleton by Ras”. Cell 89 (3): 457–67. (May 1997). doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80226-3. PMID 9150145.

- ^ “Erbin suppresses the MAP kinase pathway”. J. Biol. Chem. 278 (2): 1108–14. (January 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M205413200. PMID 12379659.

- ^ a b “X-linked and cellular IAPs modulate the stability of C-RAF kinase and cell motility”. Nat. Cell Biol. 10 (12): 1447–55. (December 2008). doi:10.1038/ncb1804. PMID 19011619.

- ^ “Raf exists in a native heterocomplex with hsp90 and p50 that can be reconstituted in a cell-free system”. J. Biol. Chem. 268 (29): 21711–6. (October 1993). PMID 8408024.

- ^ a b c “Mechanism of suppression of the Raf/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by the raf kinase inhibitor protein”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 (9): 3079–85. (May 2000). doi:10.1128/mcb.20.9.3079-3085.2000. PMC 85596. PMID 10757792.

- ^ “MEKK1 binds raf-1 and the ERK2 cascade components”. J. Biol. Chem. 275 (51): 40120–7. (December 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.M005926200. PMID 10969079.

- ^ “Contribution of the ERK5/MEK5 pathway to Ras/Raf signaling and growth control”. J. Biol. Chem. 274 (44): 31588–92. (October 1999). doi:10.1074/jbc.274.44.31588. PMID 10531364.

- ^ “A scaffold protein in the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase signaling pathways suppresses the extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathways”. J. Biol. Chem. 275 (51): 39815–8. (December 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.C000403200. PMID 11044439.

- ^ “JSAP1, a novel jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK)-binding protein that functions as a Scaffold factor in the JNK signaling pathway”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 (11): 7539–48. (November 1999). doi:10.1128/mcb.19.11.7539. PMC 84763. PMID 10523642.

- ^ “Interaction between active Pak1 and Raf-1 is necessary for phosphorylation and activation of Raf-1”. J. Biol. Chem. 277 (6): 4395–405. (February 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.M110000200. PMID 11733498.

- ^ a b “Rb and prohibitin target distinct regions of E2F1 for repression and respond to different upstream signals”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 (11): 7447–60. (November 1999). doi:10.1128/mcb.19.11.7447. PMC 84738. PMID 10523633.

- ^ a b c d e f “14-3-3 isotypes facilitate coupling of protein kinase C-zeta to Raf-1: negative regulation by 14-3-3 phosphorylation”. Biochem. J. 345 (2): 297–306. (January 2000). doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3450297. PMC 1220759. PMID 10620507.

- ^ “Effect of phosphorylation on activities of Rap1A to interact with Raf-1 and to suppress Ras-dependent Raf-1 activation”. J. Biol. Chem. 274 (1): 48–51. (January 1999). doi:10.1074/jbc.274.1.48. PMID 9867809.

- ^ “The strength of interaction at the Raf cysteine-rich domain is a critical determinant of response of Raf to Ras family small GTPases”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 (9): 6057–64. (September 1999). doi:10.1128/mcb.19.9.6057. PMC 84512. PMID 10454553.

- ^ “Rheb binds and regulates the mTOR kinase”. Curr. Biol. 15 (8): 702–13. (April 2005). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.053. PMID 15854902.

- ^ “Regulation of B-Raf kinase activity by tuberin and Rheb is mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-independent”. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (29): 29930–7. (July 2004). doi:10.1074/jbc.M402591200. PMID 15150271.

- ^ “Rheb interacts with Raf-1 kinase and may function to integrate growth factor- and protein kinase A-dependent signals”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 (2): 921–33. (February 1997). doi:10.1128/mcb.17.2.921. PMC 231818. PMID 9001246.

- ^ “Signal transduction elements of TC21, an oncogenic member of the R-Ras subfamily of GTP-binding proteins”. Oncogene 18 (43): 5860–9. (October 1999). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202968. PMID 10557073.

- ^ a b “Raf-1 physically interacts with Rb and regulates its function: a link between mitogenic signaling and cell cycle regulation”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 (12): 7487–98. (December 1998). doi:10.1128/mcb.18.12.7487. PMC 109329. PMID 9819434.

- ^ “Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper inhibits the Raf-extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by binding to Raf-1”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 (22): 7929–41. (November 2002). doi:10.1128/mcb.22.22.7929-7941.2002. PMC 134721. PMID 12391160.

- ^ “Role of the 14-3-3 C-terminal loop in ligand interaction”. Proteins 49 (3): 321–5. (November 2002). doi:10.1002/prot.10210. PMID 12360521.

- ^ “Isoform-specific localization of A-RAF in mitochondria”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 (13): 4870–8. (July 2000). doi:10.1128/mcb.20.13.4870-4878.2000. PMC 85938. PMID 10848612.

- ^ a b c “14-3-3 proteins associate with A20 in an isoform-specific manner and function both as chaperone and adapter molecules”. J. Biol. Chem. 271 (33): 20029–34. (August 1996). doi:10.1074/jbc.271.33.20029. PMID 8702721.

- ^ a b “14-3-3 proteins associate with cdc25 phosphatases”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (17): 7892–6. (August 1995). Bibcode: 1995PNAS...92.7892C. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.17.7892. PMC 41252. PMID 7644510.

- ^ a b “Large-scale mapping of human protein-protein interactions by mass spectrometry”. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3 (1): 89. (2007). doi:10.1038/msb4100134. PMC 1847948. PMID 17353931.

- ^ “14-3-3Gamma interacts with and is phosphorylated by multiple protein kinase C isoforms in PDGF-stimulated human vascular smooth muscle cells”. DNA Cell Biol. 18 (7): 555–64. (July 1999). doi:10.1089/104454999315105. PMID 10433554.

- ^ “Phosphorylation-dependent interaction of kinesin light chain 2 and the 14-3-3 protein”. Biochemistry 41 (17): 5566–72. (April 2002). doi:10.1021/bi015946f. PMID 11969417.

- ^ “Activation-modulated association of 14-3-3 proteins with Cbl in T cells”. J. Biol. Chem. 271 (24): 14591–5. (June 1996). doi:10.1074/jbc.271.24.14591. PMID 8663231.

- ^ “14-3-3 zeta negatively regulates raf-1 activity by interactions with the Raf-1 cysteine-rich domain”. J. Biol. Chem. 272 (34): 20990–3. (August 1997). doi:10.1074/jbc.272.34.20990. PMID 9261098.

- ^ “Calyculin A-induced vimentin phosphorylation sequesters 14-3-3 and displaces other 14-3-3 partners in vivo”. J. Biol. Chem. 275 (38): 29772–8. (September 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.M001207200. PMID 10887173.

- ^ “Characterization of the interaction of Raf-1 with ras p21 or 14-3-3 protein in intact cells”. FEBS Lett. 368 (2): 321–5. (July 1995). doi:10.1016/0014-5793(95)00686-4. PMID 7628630.

- ^ “Integration of calcium and cyclic AMP signaling pathways by 14-3-3”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 (2): 702–12. (January 2000). doi:10.1128/MCB.20.2.702-712.2000. PMC 85175. PMID 10611249.

関連文献

[編集]- “Structure-function analysis of Bcl-2 family proteins. Regulators of programmed cell death”. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 406: 99–112. (1997). doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-0274-0_10. PMID 8910675.

- “Structure–function relationships in HIV-1 Nef”. EMBO Rep. 2 (7): 580–5. (2001). doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve141. PMC 1083955. PMID 11463741.

- “Untying the regulation of the Raf-1 kinase”. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 404 (1): 3–9. (2002). doi:10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00244-8. PMID 12127063.

- “HIV-1 Nef control of cell signalling molecules: multiple strategies to promote virus replication”. J. Biosci. 28 (3): 323–35. (2004). doi:10.1007/BF02970151. PMID 12734410.

- “Medullary thyroid cancer: the functions of raf-1 and human achaete-scute homologue-1”. Thyroid 15 (6): 511–21. (2006). doi:10.1089/thy.2005.15.511. PMID 16029117.

関連項目

[編集]外部リンク

[編集]- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Noonan syndrome

- Domain structure diagrams for Raf-1, A-Raf and B-Raf.

- Drosophila pole hole - The Interactive Fly

- c-raf Proteins - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス

- Human RAF1 genome location and RAF1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.