ドリコリンコプス

| ドリコリンコプス | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

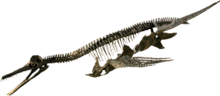

D. osborniのキャスト

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 地質時代 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 後期白亜紀チューロニアン - カンパニアン | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 分類 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 学名 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dolichorhynchops Williston, 1902 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 種 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ドリコリンコプス Dolichorhynchops は、北アメリカの後期白亜紀チューロニアンからカンパニアンの地層から発見されたポリコティルス類に属する首長竜の絶滅した属の一つで D. osborni、D. bonneri、D. tropicensisの三種[1] と疑わしい第四の種、D. herschelensisが知られている[2] 。属名は古代ギリシャ語で「長い鼻の顔」を意味する。ドリコリンコプスは白亜紀後期では既に絶滅していた魚竜のニッチに収まった首長竜と言われている。大きく裂けた細長い口は、魚や頭足類を捕らえる為に役立った。口の中にあるたくさんの鋭い歯は、捕えた獲物を逃がさない強力なものだった。ティロサウルスなどの大型ウミトカゲ類が天敵で、ティロサウルスの化石の中から未消化のドリコリンコプスの幼体の骨が報告されている。比較的首は短いが、頸椎は20個以上あることから、かなり自由に頭部を動かす事ができたと考えられている。また櫂状の四肢は水中で高い推進力を生んでいたと思われる。化石内部から胎児の化石が見つかっている事から胎生であったと考えられる。

オスボルニ種

[編集]

ドリコリンコプス・オスボルニ Dolichorhynchops osborni の完模式標本はだいたい1900年ごろ、カンザス州・ローガン群のスモーキーヒルチョーク層上部で、ティーンエイジャーだったジョージ・フライヤー・スタンバーグによって発見された。化石はジョージと彼の父、チャールズ・ヘイゼリアス・スタンバーグによって採集され、カンザス大学に売却された。KUVP 1300[3]はウィリストンの監修の下、マーティンによって補修、組み立てが行われた。

1918年、チャールズ・スタンバーグは、本種を腹の中に収めたティロサウルスを発見した[4] 。

スタンバーグは1926年に再度、より完全でない標本を発見した。彼は博物館にその標本を売るための努力として、頭骨の詳細な写真を撮った[5] 。その標本は最終的に石膏に置き換えられたものが組立骨格とされ、ハーバード大学比較動物学博物館に購入された。標本番号は MCZ 1064[6]。それは、1950年代まで展示されていた。

FHSM VP-404[7]は1950年代初頭にローガン群のラッセルスプリングの近くでマリオン・ボナーによって発見された。 それは恐らく既知の本種の中で最も完全な標本である。全長は約3m。頭骨[8]は平たくぶっ潰れていたが、状態は良い。この標本は1957年に記載されたが、当初はトリナクロメルムという別属に分類された。

本種の現在までに知られている全ての標本はカンザスのスモーキーヒルチョーク層上部から見つかっている。2003年にエバーハート は最初の標本は下層(コニアス階からサントン階)からの産出だと指摘した。2005年、本種の最初の標本はジュウェル群ニオブララ累層のフォートヘイズライムストーン産であったと指摘された。これはこの地層におけるポリコティルス類の最初の記録である[9]。

種小名はヘンリー・フェアフィールド・オズボーンへの献名である。

ボンネリ種

[編集]

2つの非常に大きなポリコティルス類標本(KUVP 40001 と 40002[10]) がワイオミングのパイアー頁岩で発見され、アダムズが1977年に自身の修士論文で報告した[11]。後の1997年、彼女は正式にその標本をトリナクロメルム属の新種、トリナクロメルム・ボンネリ (T. bonneri)として記録した。当時彼女は気づかなかったが、カーペンターが1996年に標本が別の種を表しているのではないか、あるいはオスボルニ種の大型個体ではないかという事について疑問を提起し、ポリコティルス科を提唱しドリコリンコプスをトリナクロメルムから分離した。2008年の研究ではトリナクロメルム・ボンネリはドリコリンコプスの種のバリエーションの一つであると結論づけられた[12]。

ヘルスケレンシス種

[編集]D. herschelensis は2005年に佐藤たまきによって新種記載された。カナダ・サスカチュワン州ハーシェル近郊のベアパウ累層(カンパニアン後期~マーストリヒチアン)で発見されたもので、種小名はハーシェルに因む。 地層は砂岩、泥岩、頁岩で成っており、陸地の侵食が始まる前には西部内陸海路だった。

模式標本はばらけた状態で発見された。頭骨、下顎骨、肋骨、骨盤、肩甲骨は全て回収されたが、脊椎は不完全である。 そのため、脊椎の正確な数はわからない。四肢は9個の末節骨や細々した骨を除いて全て失っている。

その標本は骨の癒合具合から1頭の成体であると信じられている。また近縁種よりも小型であるとも考えられている。 オスボルニ種やボンネリ種の亜成体はヘルスケレンシスの成体よりも大きい。全長は2.5から3mと推定されている。鼻面は長く薄い。無数の歯槽をもつが、細く鋭い歯はほとんど残っていない。

分類

[編集]

以下はケッチャムとベンソンによる2011年のポリコティルス類の類縁関係を示したクラドグラム[2]。

| プレシオサウルス亜目 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

出典

[編集]- ^ Schmeisser McKean 2011

- ^ a b Hilary F. Ketchum; Roger B. J. Benson (2011). “A new pliosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Oxford Clay Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) of England: evidence for a gracile, longirostrine grade of Early-Middle Jurassic pliosaurids”. Special Papers in Palaeontology 86: 109–129. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01083.x.

- ^ “Image: plio-lrg.jpg, (2175 × 600 px)”. oceansofkansas.com. 2015年9月5日閲覧。

- ^ “Tylosaur food”. oceansofkansas.com. 2015年9月5日閲覧。

- ^ “Image: mcz5086a.jpg, (1336 × 742 px)”. oceansofkansas.com. 2015年9月5日閲覧。

- ^ “Image: 1064-4.jpg, (1000 × 297 px)”. oceansofkansas.com. 2015年9月5日閲覧。

- ^ “Image: vp-404.jpg, (1160 × 404 px)”. oceansofkansas.com. 2015年9月5日閲覧。

- ^ “VP-404 skull”. oceansofkansas.com. 2015年9月5日閲覧。[リンク切れ]

- ^ Everhart, Decker & Decker 2006

- ^ “Image: KU40001-4.jpg, (589 × 500 px)”. oceansofkansas.com. 2015年9月5日閲覧。

- ^ Adams 1977

- ^ O'Keefe, F. R. (2008). “Cranial anatomy and taxonomy of Dolichorhynchops bonneri new combination, a polycotylid (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) from the Pierre Shale of Wyoming and South Dakota”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (3): 664–676. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[664:caatod]2.0.co;2.

参考文献

[編集]- Adams, D. A. (1977), Trinacromerum bonneri, a new polycotylid plesiosaur from the Pierre Shale of South Dakota and Wyoming, Unpublished Masters thesis, University of Kansas, 97 pages

- Adams, D. A. (1997). “Trinacromerum bonneri, new species, last and fastest pliosaur of the Western Interior Seaway”. Texas Journal of Science 49 (3): 179–198.

- Albright III, L. B.; Gillette, D. D.; Titus, A. L. (2007b). “Plesiosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Turonian) Tropic Shale of southern Utah, part 2: polycotylidae”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[41:PFTUCC]2.0.CO;2. オリジナルの2011-09-28時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- Bonner, O. W. (1964), An osteological study of Nyctosaurus and Trinacromerum with a description of a new species of Nyctosaurus, Unpub. Masters Thesis, Fort Hays State University, 63 pages

- Carpenter, K. (1996). “A Review of short-necked plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior, North America”. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläeontologie Abhandlungen (Stuttgart) 201 (2): 259–287.

- Everhart, M. J. (2003). “First records of plesiosaur remains in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk Member (Upper Coniacian) of the Niobrara Formation in western Kansas”. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 106 (3–4): 139–148. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2003)106[0139:FROPRI]2.0.CO;2.

- Everhart, M. J. (2004a). “Plesiosaurs as the food of mosasaurs; new data on the stomach contents of a Tylosaurus proriger (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Formation of western Kansas”. The Mosasaur 7: 41–46.

- Everhart, M. J. (2004b). “New data regarding the skull of Dolichorhynchops osborni (Plesiosauroidea: Polycotylidae) from rediscovered photos of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology specimen”. Paludicola 4 (3): 74–80.

- Everhart, M. J. (2005). Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press

- Everhart, M.J.; Decker, R.; Decker, P. (2006). “Earliest remains of Dolichorhynchops osborni (Plesiosauria: Polycotylidae) from the basal Fort Hays Limestone, Jewell County, Kansas”. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 109 (3–4): 261. (abstract)

- Everhart, M. J. (2007). Sea Monsters: Prehistoric Creatures of the Deep. ISBN 978-1-4262-0085-4

- O'Keefe, F. R. (2004). “On the cranial anatomy of the polycotylid plesiosaurs, including new material of Polycotylus latipinnis Cope, from Alabama”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24 (2): 326–340. doi:10.1671/1944.

- Sato, T. (2005). “A new Polycotylid Plesiosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Upper Cretaceous Bearpaw Formation in Saskatchewan, Canada”. Journal of Paleontology 79 (5): 969–980. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079[0969:ANPPRS]2.0.CO;2.

- Schmeisser McKean, Rebecca (2011). “A new species of polycotylid plesiosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Turonian of Utah: extending the stratigraphic range of Dolichorhynchops”. Cretaceous Research 34: 184–199. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.10.017.

- Sternberg, C. H. (1922). “Explorations of the Permian of Texas and the chalk of Kansas, 1918”. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 30 (1): 119–120. doi:10.2307/3624047.

- Sternberg, G. F.; Walker, M. V. (1957). “Report on a plesiosaur skeleton from western Kansas”. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 60 (1): 86–87. doi:10.2307/3627008.

- Williston, S. W. (1902). “Restoration of Dolichorhynchops osborni, a new Cretaceous plesiosaur”. Kansas University Science Bulletin 1 (9): 241–244.

- Williston, S. W. (1903). “North American plesiosaurs”. Field Columbian Museum, Pub. 73. Geological Series 2 (1): 1–79.