人工智能的进展

| 人工智能系列内容 |

|---|

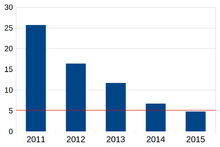

每年人工智能的错误率红线-受训人员在特定任务上的错误率。

人工智能( AI )的进展是指人工智能领域随着时间的推移所取得的进步、里程碑和突破。人工智能是计算机科学领域的一个多学科分支,旨在创建能够执行通常需要人类执行任务的机器和系统。人工智能技术已广泛应用于医疗诊断、金融领域、机器人操控、法律、科学探索、电子游戏和玩具等领域。然而,许多人工智能应用程序并不被视为人工智能:“许多尖端人工智能已经应用到通用应用程序中,但通常会被称为人工智能,因为一旦这项技术广泛应用,它就不再被成为人工智能了。” [1] [2] “这种现象使得许多人工智能技术已经应用到各行业的基础设施中,成为日常生活的一部分。” [3]在20世纪90年代末至21世纪初,人工智能技术被广泛应用于各种大型系统中, [3] [4]但当时该领域并未因这些成功而受到足够的赞誉和认可。

卡普兰和 亨莱因按将人工智能分为三个演进阶段:1)狭义人工智能——仅将人工智能应用于特定任务; 2)通用人工智能——将人工智能应用于多个领域,并能够自主解决甚至未曾设计过的问题; 3)超级人工智能——将人工智能应用于任何具备科学创造力、社交技能和综合智慧的领域。 [2]

为了与人类表现进行比较,人工智能可以在具体而清晰定义的问题上进行评估。此类测试被称为主题专家图灵测试。此外,通过解决较小的问题,人工智能可以实现更清晰的目标,且取得了越来越多的好成绩。

人类在所有方面的表现仍然远远优于GPT-4和在ConceptARC基准上训练的模型,这些模型在大多数方面的得分为60%,其中一个类别为77%,而人类在所有方面的得分为91%,其中一个类别为97%。 [5]

当前表现

[编辑]| 游戏名称 | 冠军年份[6] | 法律状态 (log 10 ) [7] | 博弈树复杂度(log 10 ) [7] | 完美信息博弈? | 参考号 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 跳棋(跳棋) | 1994年 | 21 | 31 | 完美的 | [8] |

| 奥赛罗(黑白棋) | 1997年 | 28 | 58 | 完美的 | [9] |

| 棋 | 1997年 | 46 | 123 | 完美的 | |

| 拼字游戏 | 2006年 | [10] | |||

| 将棋 | 2017年 | 71 | 226 | 完美的 | [11] |

| 去 | 2016年 | 172 | 360 | 完美的 | |

| 两人无限下注德州扑克 | 2017年 | 不完善 | [12] | ||

| 《星际争霸》 | - | 270+ | 不完善 | [13] | |

| 《星际争霸2》 | 2019年 | 不完善 | [14] |

有许多有用的能力可以被归类为展示某种形式的智能。这为我们更好地了解人工智能在不同领域中的相对成功提供了更多见解。

人工智能就像电力或蒸汽机中的热能一样,是一种通用技术。对于人工智能擅长哪些任务,目前还没有达成共识。 [15]莫拉维克悖论的某些版本写到,人类更有可能在生理灵活性方面等直接成为自然选择目标的领域,胜过机器。 [16]尽管AlphaZero等项目已经成功地从零开始生成自己的知识,但许多其他机器学习项目仍然需要大量的数据集训练 [17] [18]研究人员安德鲁·吴(Andrew Ng)表示,作为“高度不完美的经验法则”,“几乎任何人类只需不到一秒钟的思维就能完成的事情,我们现在或在不久的将来可能可以通过人工智能实现自动化。” [19]

游戏为评估进度提供了一个高基准;许多游戏都拥有庞大的职业玩家群体和成熟的竞技评级系统。2016年,Deep Mind公司的阿尔法狗击败世界顶级职业围棋选手李世乭,证明了人工智能在围棋比赛中的竞争优势,从而结束了传统棋类游戏基准的时代。[20]在信息不对称的游戏中,人工智能在博弈论领域面临新的挑战;这一领域最显著的里程碑之一是冷扑大师在2017年的扑克比赛中取得胜利。[21] [22]电子竞技继续为评估人工智能进展提供额外的基准; Facebook AI、 DeepMind和其他公司已经涉足备受欢迎的《星际争霸》视频游戏系列。 [23] [24]

人工智能测试的结果有以下几种::

- 表现最佳:无法表现得更好(注意:其中一些条目是由人类解决的)

- 表现超越人类:表现优于所有人类

- 表现优于人类:表现优于大多数人类

- 表现接近于人类:表现与大多数人类相似

- 表现低于人类:表现比大多数人差

表现最佳

[编辑]- 井字游戏

- 四子棋:(1988年)

- 跳棋(又名 8x8 跳棋):弱解 (2007年) [25]

- 魔方:大部分已解决 (2010年) [26]

- 一对一限注德州扑克:这种策略在统计学上表现出色,即“在有限的人类寿命内,无法通过有限的人类游戏经验来确定它是否是一个确切的解决方案”(2015年) [27]

表现超越人类

[编辑]- 奥赛罗(又称黑白棋):(约1997年)[9]

- 拼字游戏: [28] [29] (2006年) [10]

- 双陆棋:(约1995–2002年) [30] [31]

- 国际象棋:超级计算机(约1997年);个人电脑(约2006年); [32]移动电话(约2009年); [33]计算机击败人类+计算机(约 2017年) [34]

- 《危险边缘》 :问答,虽然机器没有使用语音识别(2011年) [35] [36]

- 印度斗兽棋:(2015年) [37] [38]

- 日本将棋:(约2017年)[11]

- 围棋:(2017年)[39]

- 一对一无限注德州扑克:(2017年)[12]

- 六人无限注德州扑克:(2019年 )[40]

- 《跑车浪漫旅》:(2022年)[41]

表现优于人类

[编辑]- 填字游戏:(约2012年)[42] [43]

- 自由公民:(2016年) [44]

- 《刀塔 2》 :(2018年) [45]

- 桥牌游戏:根据2009年的一项评价,“最优秀的程序正在达到专业级别的(桥牌)卡牌游戏水平”,但不涉及投标过程。 [46]

- 《星际争霸 II》 :(2019年) [47]

- 麻将:(2019年) [48]

- 西洋陆军棋:(2022年) [49]

- 无新闻外交:(2022年) [50]

- 《花火》: (2022年) [51]

- 自然语言处理[來源請求]</link>

表现接近于人类

[编辑]- ISO 1073-1:1976标准和类似特殊字符的光学字符识别。[來源請求]</link>[需要引用]

- 图像分类[52]

- 手写识别[53]

- 人脸识别[54]

- 视觉问答[55]

- 斯坦福大学问答数据集2.0英文阅读理解基准(2019念) [56]

- 高难度英语语言理解基准(2020年) [56]

- 部分学校理科考试(2019年) [57]

- 基于瑞文标准推理测验一些任务[58]

- 许多基于Atari 2600 游戏系统的游戏 (2015年) [59]

表现低于人类

[编辑]- 识别印刷文本的光学字符识别(接近人类对于拉丁字母书写文本的能力)

- 目标识别[需要解释]

- 可能需要机器人硬件和人工智能方面的进步的各种机器人任务,包括:

- 语音识别:“几乎等同于人类表现的水平”(2017年) [62]

- 解释能力。当前的医疗系统能够诊断某些疾病,但无法向用户解释他们为何做出这样的诊断。 [63]

- 流体智力多项测试(2020年) [58]

- 邦加德视觉认知问题,例如邦加德-洛高基准(2020年) [58] [64]

- 视觉常识推理 (VCR) 基准(截至 2020 年) [56]

- 股市预测:使用机器学习算法进行金融数据收集和处理

- 《愤怒的小鸟》视频游戏(截至 2020 年)[65]

- 在没有上下文知识的情况下难以解决的各种任务,包括:

人工智能提议性测试

[编辑]在艾伦·图灵的著名图灵测试中,他选择了语言作为测试的基础,因为语言是人类的定义特征。 而如今人们认为图灵测试容易被操纵,不再是一个有意义的基准。 [66]

费根鲍姆测试由专家系统的发明者提出,测试机器对特定主题的知识和专业知识的学习程度。 [67]微软的吉姆·格雷在 2003 年发表的一篇论文中建议将图灵测试扩展到语音理解、对话以及物体识别和行为识别这些方面。 [68]

提出的“通用智能”测试旨在比较机器、人类甚至非人类动物在尽可能通用的问题集上的表现。在极端情况下,这个测试可能包含每个可能的问题,按照科尔莫哥罗夫复杂度进行加权;然而,这些问题集往往以有限的模式匹配练习为主,其中经过调整的人工智能可以轻松超过人类的表现。 [69] [70] [71] [72] [73]

考试表现

[编辑]根据OpenAI 的数据,2023 年ChatGPT GPT-4在统一律师考试中得到的分数分高于90%的考生人。在美国学业测试考试中,GPT-4 在数学方面得分的得分高于89%的考生,在阅读和写作方面得分高于 93%的考生。在美国研究生入学考试中,它的写作测试得分高于 54%的考生,数学测试得分高于 88%的考生,口语部分得分高于 99%的考生。在 2020 年美国生物奥林匹克半决赛中,它的得分达到最高。它在多项大学预科课程考试中获得了满分“5”分的好成绩。 [74]

独立研究人员在2023年发现,ChatGPT GPT-3.5在美国医师执照考试的需要通过的三个测试中将将及格。 GPT-3.5还在明尼苏达大学四门法学院课程的考试中刚刚达到及格标准。 [74] 而GPT-4通过了通过文本材料进行评估的模拟医学情景考试。 [75] [76]

比赛情况

[编辑]许多竞赛和奖项,例如图像数据库挑战赛,促进了人工智能领域的研究。竞赛的最常见领域包括通用机器智能、对话、数据挖掘、机器人汽车以及传统游戏。 [77]

历史和当前的预测

[编辑]2016年左右,由人类未来研究所的卡佳·格雷斯及其同事进行的一项专家民意调查显示, 人工智能成为《愤怒的小鸟》游戏冠军的所需的中值预计时间为3年,成为世界扑克系列赛冠军需要4年, 而成为《星际争霸》游戏冠军则需要 6 年。在更为主观的任务方面,该调查还显示,人工智能估计需要6年才能在叠衣服工作上达到人类的工作水平,能够专业回答“容易在谷歌上找到答案的问题”需要7-10年,完成普通语音转录任务需要8年,在完成普通电话银行任务上想要达到人类水平则需要9年,而进行专业创作歌曲需要11年。此外,如果想要写一本《纽约时报》畅销书或赢得普特南数学竞赛,人工智能则需要30年以上的时间。[78] [79] [80]

在国际象棋项目上的表现

[编辑]

1988 年,人工智能首次在常规锦标赛中击败了特级大师;随后更名为“深蓝” ,并于 1997 年击败了当时世界国际象棋冠军加里·卡斯帕罗夫(参见“深蓝对阵加里·卡斯帕罗夫”)。 [81]

| 预测的时间 | 预测到来时间 | 年数 | 预测人 | 同期来源 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957年 | 1967年或更早 | 10或更少 | 赫伯特·A·西蒙,经济学家[82] | |

| 1990年 | 2000年或更早 | 10或更少 | 雷·库兹韦尔,未来学家 | 《智能机器时代》[83] |

在围棋项目上的表现

[编辑]阿尔法狗于 2015 年 10 月击败了欧洲围棋冠军,并于 2016 年 3 月击败了世界顶级棋手之一李世乭(参见AlphaGo 与李世乭)。据《科学美国人》和其他消息称,多数观察者曾预计要等至少十年才能见到超越人类水平的计算机围棋表现。 [84] [85] [86]

| 预测的时间 | 预测到来时间 | 年数 | 预测人 | 联系 | 同期来源 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997年 | 2100年或之后 | 103年或更多 | 皮特·赫特——物理学家和围棋迷 | 普林斯顿高等研究院 | 《纽约时报》[87] [88] |

| 2007年 | 2017年或更早 | 10年或更少 | 徐凤雄、深蓝领衔 | 微软亚洲研究院 | 《科技纵览》杂志[89] [90] |

| 2014年 | 2024年 | 10年 | 雷米·库隆—— 围棋计算机程序员 | 疯狂的石头 | 《连线》杂志[90] [91] |

达到人类水平的通用人工智能(AGI)

[编辑]人工智能先驱和经济学家赫伯特·A·西蒙 (Herbert A. Simon)在 1965 年错误地预测到:“二十年内,机器将能够完成人类能做的任何工作”。马文·明斯基 (Marvin Minsky)在 1970 年也曾写道:“在20-30年之内……创造人工智能的问题将得到实质性解决。” [92]

2012年和2013年进行的四项民意调查显示,专家对通用人工智能何时到来的平均估计为2040年至2050年,这具体取决于不同的民意调查。 [93] [94]

根据2016年左右的格雷斯民意调查显示,结果因不同的提问方式而异。那些被问及“在不受帮助的情况下,机器何时能够比人类更好、更便宜地完成每项任务”给出的中值答案为45年,其中有10%人认为这个情况的可能在9年内发生。其他受访者被问及“何时所有职业都能够实现完全自动化。也就是说,对于任何职业,机器都可以更好、性价比更好地执行任务”给出的答案估计中值为122年,其中有10%的人认为这个情况的可能在20年内发生。 对于“人工智能研究员”何时能够完全自动化的中值回答约为90年。虽然并未发现专业度和乐观主义之间的联系,但亚洲研究员的平均乐观主义值要比北美研究员高得多;亚洲人平均预测“完成每项任务”需要30年,而北美人则预测需要74年。 [78] [79] [80]

| 预测的时间 | 预测到来时间 | 年数 | 预测人 | 同期来源 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965年 | 1985年或更早 | 20年或更少 | 赫伯特·西蒙 | 男性和管理自动化的形态[92] [95] |

| 1993年 | 2023年或更早 | 30年或以下 | 弗诺·文奇,科幻小说作家 | “即将到来的技术奇点” [96] |

| 1995年 | 2040年或更早 | 45年或以下 | 汉斯·莫拉维克 ,机器人研究员 | 《连线》杂志[97] |

| 2008年 | 永远不会/遥远的未来[note 1] | 戈登·E·摩尔-摩尔定律的发明者 | 《科技纵览》杂志[98] | |

| 2017年 | 2029年 | 12年 | 雷·库兹韦尔 | 采访[99] |

参见

[编辑]- 人工智能的应用

- 人工智能项目清单

- 新兴技术清单

参考资料

[编辑]- ^ AI set to exceed human brain power 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2008-02-19. CNN.com (July 26, 2006)

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Kaplan, Andreas; Haenlein, Michael. Siri, Siri, in my hand: Who's the fairest in the land? On the interpretations, illustrations, and implications of artificial intelligence. Business Horizons. 2019, 62: 15–25. S2CID 158433736. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2018.08.004.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Kurtzweil 2005

- ^ National Research Council, Developments in Artificial Intelligence, Funding a Revolution: Government Support for Computing Research, National Academy Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-309-06278-7, OCLC 246584055 under "Artificial Intelligence in the 90s"

- ^ Biever, Celeste. ChatGPT broke the Turing test — the race is on for new ways to assess AI. Nature. 25 July 2023 [26 July 2023]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-26).

- ^ Approximate year AI started beating top human experts

- ^ 7.0 7.1 van den Herik, H.Jaap; Uiterwijk, Jos W.H.M.; van Rijswijck, Jack. Games solved: Now and in the future. Artificial Intelligence. January 2002, 134 (1–2): 277–311. doi:10.1016/S0004-3702(01)00152-7

.

.

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis C. How Checkers Was Solved. The Atlantic. 2017 [6 May 2018]. (原始内容存档于6 May 2018).

- ^ 9.0 9.1 www.othello-club.de. berg.earthlingz.de. [2018-07-15]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-15).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Webley, Kayla. Top 10 Man-vs.-Machine Moments. Time. 15 February 2011 [28 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于26 December 2017).

- ^ 11.0 11.1 Shogi prodigy breathes new life into the game | The Japan Times. The Japan Times. [2018-07-15]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-15) (美国英语).

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Brown, Noam; Sandholm, Tuomas. Superhuman AI for heads-up no-limit poker: Libratus beats top professionals. Science. 2017, 359 (6374): 418–424. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..418B. PMID 29249696. doi:10.1126/science.aao1733

.

.

- ^ Facebook Quietly Enters StarCraft War for AI Bots, and Loses. WIRED. 2017 [6 May 2018]. (原始内容存档于7 May 2018).

- ^ Sample, Ian. AI becomes grandmaster in 'fiendishly complex' StarCraft II. The Guardian. 30 October 2019 [28 February 2020]. (原始内容存档于29 December 2020).

- ^ Brynjolfsson, Erik; Mitchell, Tom. What can machine learning do? Workforce implications. Science. 22 December 2017, 358 (6370): 1530–1534 [7 May 2018]. Bibcode:2017Sci...358.1530B. PMID 29269459. S2CID 4036151. doi:10.1126/science.aap8062. (原始内容存档于29 September 2021) (英语).

- ^ IKEA furniture and the limits of AI. The Economist. 2018 [24 April 2018]. (原始内容存档于24 April 2018) (英语).

- ^ Sample, Ian. 'It's able to create knowledge itself': Google unveils AI that learns on its own. the Guardian. 18 October 2017 [7 May 2018]. (原始内容存档于19 October 2017) (英语).

- ^ The AI revolution in science. Science | AAAS. 5 July 2017 [7 May 2018]. (原始内容存档于14 December 2021) (英语).

- ^ Will your job still exist in 10 years when the robots arrive?. South China Morning Post. 2017 [7 May 2018]. (原始内容存档于7 May 2018) (英语).

- ^ Mokyr, Joel. The Technology Trap: Capital Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation. By Carl Benedikt Frey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019. Pp. 480. $29.95, hardcover.. The Journal of Economic History. 2019-11-01, 79 (4): 1183–1189 [2020-11-25]. ISSN 0022-0507. S2CID 211324400. doi:10.1017/s0022050719000639. (原始内容存档于2023-02-02).

- ^ Borowiec, Tracey Lien, Steven. AlphaGo beats human Go champ in milestone for artificial intelligence. Los Angeles Times. 2016 [7 May 2018]. (原始内容存档于13 May 2018).

- ^ Brown, Noam; Sandholm, Tuomas. Superhuman AI for heads-up no-limit poker: Libratus beats top professionals. Science. 26 January 2018, 359 (6374): 418–424. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..418B. PMID 29249696. S2CID 5003977. doi:10.1126/science.aao1733

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ Ontanon, Santiago; Synnaeve, Gabriel; Uriarte, Alberto; Richoux, Florian; Churchill, David; Preuss, Mike. A Survey of Real-Time Strategy Game AI Research and Competition in StarCraft. IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games. December 2013, 5 (4): 293–311. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.406.2524

. S2CID 5014732. doi:10.1109/TCIAIG.2013.2286295.

. S2CID 5014732. doi:10.1109/TCIAIG.2013.2286295.

- ^ Facebook Quietly Enters StarCraft War for AI Bots, and Loses. WIRED. 2017 [7 May 2018]. (原始内容存档于2 February 2023).

- ^ Schaeffer, J.; Burch, N.; Bjornsson, Y.; Kishimoto, A.; Muller, M.; Lake, R.; Lu, P.; Sutphen, S. Checkers is solved. Science. 2007, 317 (5844): 1518–1522. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1518S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.95.5393

. PMID 17641166. S2CID 10274228. doi:10.1126/science.1144079.

. PMID 17641166. S2CID 10274228. doi:10.1126/science.1144079.

- ^ God's Number is 20. [2011-08-07]. (原始内容存档于2013-07-21).

- ^ Bowling, M.; Burch, N.; Johanson, M.; Tammelin, O. Heads-up limit hold'em poker is solved. Science. 2015, 347 (6218): 145–9. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..145B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.697.72

. PMID 25574016. S2CID 3796371. doi:10.1126/science.1259433.

. PMID 25574016. S2CID 3796371. doi:10.1126/science.1259433.

- ^ In Major AI Breakthrough, Google System Secretly Beats Top Player at the Ancient Game of Go. WIRED. [28 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于2 February 2017).

- ^ Sheppard, B. World-championship-caliber Scrabble. Artificial Intelligence. 2002, 134 (1–2): 241–275. doi:10.1016/S0004-3702(01)00166-7

.

.

- ^ Tesauro, Gerald. Temporal difference learning and TD-Gammon. Communications of the ACM. March 1995, 38 (3): 58–68 [2008-03-26]. S2CID 8763243. doi:10.1145/203330.203343

. (原始内容存档于2013-01-11).

. (原始内容存档于2013-01-11).

- ^ Tesauro, Gerald. Programming backgammon using self-teaching neural nets. Artificial Intelligence. January 2002, 134 (1–2): 181–199. doi:10.1016/S0004-3702(01)00110-2.

...at least two other neural net programs also appear to be capable of superhuman play

- ^ Kramnik vs Deep Fritz: Computer wins match by 4:2. Chess News. 2006-12-05 [2018-07-15]. (原始内容存档于2018-11-25) (美国英语).

- ^ The Week in Chess 771. theweekinchess.com. [2018-07-15]. (原始内容存档于2018-11-15).

- ^ Nickel, Arno. Zor Winner in an Exciting Photo Finish. www.infinitychess.com. Innovative Solutions. May 2017 [2018-07-17]. (原始内容存档于2018-08-17).

... on third place the best centaur ...

- ^ Markoff, John. Computer Wins on 'Jeopardy!': Trivial, It's Not. The New York Times. 2011-02-16 [2023-02-22]. ISSN 0362-4331. (原始内容存档于2014-10-22) (美国英语).

- ^ Jackson, Joab. IBM Watson Vanquishes Human Jeopardy Foes. PC World. IDG News. [2011-02-17]. (原始内容存档于2011-02-20).

- ^ The Arimaa Challenge. arimaa.com. [2018-07-15]. (原始内容存档于2010-03-22).

- ^ Roeder, Oliver. The Bots Beat Us. Now What?. FiveThirtyEight. 10 July 2017 [28 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于28 December 2017).

- ^ AlphaGo beats Ke Jie again to wrap up three-part match. The Verge. [2018-07-15]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-15).

- ^ Blair, Alan; Saffidine, Abdallah. AI surpasses humans at six-player poker. Science. 30 August 2019, 365 (6456): 864–865 [30 June 2022]. Bibcode:2019Sci...365..864B. PMID 31467208. S2CID 201672421. doi:10.1126/science.aay7774. (原始内容存档于18 July 2022).

- ^ Sony's new AI driver achieves 'reliably superhuman' race times in Gran Turismo. The Verge. [2022-07-19]. (原始内容存档于2022-07-20).

- ^ Proverb: The probabilistic cruciverbalist. By Greg A. Keim, Noam Shazeer, Michael L. Littman, Sushant Agarwal, Catherine M. Cheves, Joseph Fitzgerald, Jason Grosland, Fan Jiang, Shannon Pollard, and Karl Weinmeister. 1999. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 710-717. Menlo Park, Calif.: AAAI Press.

- ^ Wernick, Adam. 'Dr. Fill' vies for crossword solving supremacy, but still comes up short. Public Radio International. 24 Sep 2014 [Dec 27, 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017-12-28).

The first year, Dr. Fill came in 141st out of about 600 competitors. It did a little better the second-year; last year it was 65th

- ^ Arago's AI can now beat some human players at complex civ strategy games.. TechCrunch. 6 December 2016 [20 July 2022]. (原始内容存档于5 June 2022).

- ^ AI bots trained for 180 years a day to beat humans at Dota 2.. The Verge. 25 June 2018 [17 July 2018]. (原始内容存档于25 June 2018).

- ^ Bethe, P. M. (2009). The state of automated bridge play.

- ^ AlphaStar: Mastering the Real-Time Strategy Game StarCraft II. [2022-07-19]. (原始内容存档于2022-07-22).

- ^ Suphx: The World Best Mahjong AI. Microsoft. [2022-07-19]. (原始内容存档于2022-07-19).

- ^ Deepmind AI Researchers Introduce 'DeepNash', An Autonomous Agent Trained With Model-Free Multiagent Reinforcement Learning That Learns To Play The Game Of Stratego At Expert Level.. MarkTechPost. 9 July 2022 [19 July 2022]. (原始内容存档于9 July 2022).

- ^ Bakhtin, Anton; Wu, David. Mastering the Game of No-Press Diplomacy via Human-Regularized Reinforcement Learning and Planning. 11 October 2022. arXiv:2210.05492

[cs.GT].

[cs.GT].

- ^ Hu, Hengyuan; Wu, David. Human-AI Coordination via Human-Regularized Search and Learning. 11 October 2022. arXiv:2210.05125

[cs.AI].

[cs.AI].

- ^ Microsoft researchers say their newest deep learning system beats humans -- and Google - VentureBeat - Big Data - by Jordan Novet. VentureBeat. 2015-02-10 [2017-09-08]. (原始内容存档于2017-08-09).

- ^ Santoro, Adam; Bartunov, Sergey. One-shot Learning with Memory-Augmented Neural Networks. 19 May 2016. arXiv:1605.06065

[cs.LG].

[cs.LG].

- ^ Man Versus Machine: Who Wins When It Comes to Facial Recognition?. Neuroscience News. 2018-12-03 [2022-07-20]. (原始内容存档于2022-07-20).

- ^ Yan, Ming; Xu, Haiyang. Achieving Human Parity on Visual Question Answering. 17 November 2021. arXiv:2111.08896

[cs.CL].

[cs.CL].

- ^ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Zhang, D., Mishra, S., Brynjolfsson, E., Etchemendy, J., Ganguli, D., Grosz, B., ... & Perrault, R. (2021). The AI index 2021 annual report. AI Index (Stanford University). arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.06312.

- ^ Metz, Cade. A Breakthrough for A.I. Technology: Passing an 8th-Grade Science Test. The New York Times. 4 September 2019 [5 January 2023]. (原始内容存档于5 January 2023).

- ^ 58.0 58.1 58.2 van der Maas, Han L.J.; Snoek, Lukas; Stevenson, Claire E. How much intelligence is there in artificial intelligence? A 2020 update. Intelligence. July 2021, 87: 101548. S2CID 236236331. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2021.101548

.

.

- ^ McMillan, Robert. Google's AI Is Now Smart Enough to Play Atari Like the Pros. Wired. 2015 [5 January 2023]. (原始内容存档于5 January 2023).

- ^ Robots with legs are getting ready to walk among us. The Verge. [28 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于28 December 2017).

- ^ Hurst, Nathan. Why Funny, Falling, Soccer-Playing Robots Matter. Smithsonian. [28 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于28 December 2017) (英语).

- ^ The Business of Artificial Intelligence. Harvard Business Review. 18 July 2017 [28 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于29 December 2017) (英语).

- ^ Brynjolfsson, E., & Mitchell, T. (2017). What can machine learning do? Workforce implications. Science, 358(6370), 1530-1534.

- ^ Nie, W., Yu, Z., Mao, L., Patel, A. B., Zhu, Y., & Anandkumar, A. (2020). Bongard-logo: A new benchmark for human-level concept learning and reasoning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 16468-16480.

- ^ Stephenson, Matthew; Renz, Jochen; Ge, Xiaoyu. The computational complexity of Angry Birds. Artificial Intelligence. March 2020, 280: 103232. S2CID 56475869. arXiv:1812.07793

. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2019.103232.

. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2019.103232. Despite many different attempts over the past five years the problem is still largely unsolved, with AI approaches far from human-level performance.

- ^ Schoenick, Carissa; Clark, Peter; Tafjord, Oyvind; Turney, Peter; Etzioni, Oren. Moving beyond the Turing Test with the Allen AI Science Challenge. Communications of the ACM. 23 August 2017, 60 (9): 60–64. S2CID 6383047. arXiv:1604.04315

. doi:10.1145/3122814.

. doi:10.1145/3122814.

- ^ Feigenbaum, Edward A. Some challenges and grand challenges for computational intelligence. Journal of the ACM. 2003, 50 (1): 32–40. S2CID 15379263. doi:10.1145/602382.602400.

- ^ Gray, Jim. What Next? A Dozen Information-Technology Research Goals. Journal of the ACM. 2003, 50 (1): 41–57. Bibcode:1999cs.......11005G. S2CID 10336312. arXiv:cs/9911005

. doi:10.1145/602382.602401.

. doi:10.1145/602382.602401.

- ^ Hernandez-Orallo, Jose. Beyond the Turing Test. Journal of Logic, Language and Information. 2000, 9 (4): 447–466. S2CID 14481982. doi:10.1023/A:1008367325700.

- ^ Kuang-Cheng, Andy Wang. International licensing under an endogenous tariff in vertically-related markets. Journal of Economics. 2023 [2023-04-23]. (原始内容存档于2024-04-14) (英语).

- ^ Dowe, D. L.; Hajek, A. R. A computational extension to the Turing Test. Proceedings of the 4th Conference of the Australasian Cognitive Science Society. 1997. (原始内容存档于28 June 2011).

- ^ Hernandez-Orallo, J.; Dowe, D. L. Measuring Universal Intelligence: Towards an Anytime Intelligence Test. Artificial Intelligence. 2010, 174 (18): 1508–1539. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.295.9079

. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2010.09.006.

. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2010.09.006.

- ^ Hernández-Orallo, José; Dowe, David L.; Hernández-Lloreda, M.Victoria. Universal psychometrics: Measuring cognitive abilities in the machine kingdom. Cognitive Systems Research. March 2014, 27: 50–74. S2CID 26440282. doi:10.1016/j.cogsys.2013.06.001. hdl:10251/50244

.

.

- ^ 74.0 74.1 Varanasi, Lakshmi. AI models like ChatGPT and GPT-4 are acing everything from the bar exam to AP Biology. Here's a list of difficult exams both AI versions have passed.. Business Insider. March 2023 [22 June 2023]. (原始内容存档于2024-06-07).

- ^ Rudy, Melissa. Latest version of ChatGPT passes radiology board-style exam, highlights AI's 'growing potential,' study finds. Fox News. 24 May 2023 [22 June 2023]. (原始内容存档于2024-04-26).

- ^ Bhayana, Rajesh; Bleakney, Robert R.; Krishna, Satheesh. GPT-4 in Radiology: Improvements in Advanced Reasoning. Radiology. 1 June 2023, 307 (5): e230987 [2024-01-24]. PMID 37191491. S2CID 258716171. doi:10.1148/radiol.230987. (原始内容存档于2023-06-22).

- ^ ILSVRC2017. image-net.org. [2018-11-06]. (原始内容存档于2018-11-02) (英语).

- ^ 78.0 78.1 Gray, Richard. How long will it take for your job to be automated?. BBC. 2018 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于11 January 2018) (英语).

- ^ 79.0 79.1 AI will be able to beat us at everything by 2060, say experts. New Scientist. 2018 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于31 January 2018).

- ^ 80.0 80.1 Grace, K., Salvatier, J., Dafoe, A., Zhang, B., & Evans, O. (2017). When will AI exceed human performance? Evidence from AI experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.08807.

- ^ McClain, Dylan Loeb. Bent Larsen, Chess Grandmaster, Dies at 75. The New York Times. 11 September 2010 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于25 March 2014).

- ^ The Business of Artificial Intelligence. Harvard Business Review. 18 July 2017 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于18 January 2018) (英语).

- ^ 4 Crazy Predictions About the Future of Art. Inc.com. 2017 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于12 September 2017) (英语).

- ^ Koch, Christof. How the Computer Beat the Go Master. Scientific American. 2016 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于6 September 2017) (英语).

- ^ 'I'm in shock!' How an AI beat the world's best human at Go. New Scientist. 2016 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于13 May 2016).

- ^ Moyer, Christopher. How Google's AlphaGo Beat a Go World Champion. The Atlantic. 2016 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于31 January 2018).

- ^ Johnson, George. To Test a Powerful Computer, Play an Ancient Game. The New York Times. 29 July 1997 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于31 January 2018).

- ^ Johnson, George. To Beat Go Champion, Google's Program Needed a Human Army. The New York Times. 4 April 2016 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于31 January 2018).

- ^ Cracking GO. IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. 2007 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于31 January 2018) (英语).

- ^ 90.0 90.1 The Mystery of Go, the Ancient Game That Computers Still Can't Win. WIRED. 2014 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于31 January 2016).

- ^ Gibney, Elizabeth. Google AI algorithm masters ancient game of Go. Nature. 28 January 2016, 529 (7587): 445–446. Bibcode:2016Natur.529..445G. PMID 26819021. S2CID 4460235. doi:10.1038/529445a

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ 92.0 92.1 Bostrom, Nick. Superintelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2013. ISBN 978-0199678112 (英语).

- ^ Khatchadourian, Raffi. The Doomsday Invention. The New Yorker. 16 November 2015 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于29 April 2019).

- ^ Müller, V. C., & Bostrom, N. (2016). Future progress in artificial intelligence: A survey of expert opinion. In Fundamental issues of artificial intelligence (pp. 555-572). Springer, Cham.

- ^ Muehlhauser, L., & Salamon, A. (2012). Intelligence explosion: Evidence and import. In Singularity Hypotheses (pp. 15-42). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- ^ Tierney, John. Vernor Vinge's View of the Future - Is Technology That Outthinks Us a Partner or a Master ?. The New York Times. 25 August 2008 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于24 December 2017).

- ^ Superhumanism. WIRED. 1995 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于2 September 2017).

- ^ Tech Luminaries Address Singularity. IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. 2008 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于30 April 2019) (英语).

- ^ Molloy, Mark. Expert predicts date when 'sexier and funnier' humans will merge with AI machines. The Telegraph. 17 March 2017 [31 January 2018]. (原始内容存档于31 January 2018).

注释

[编辑]外部链接

[编辑]Template:新兴技术

引用错误:页面中存在<ref group="note">标签,但没有找到相应的<references group="note" />标签