Bất ổn định Kelvin–Helmholtz

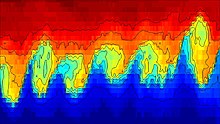

Bất ổn định Kelvin–Helmholtz (đặt tên theo Lord Kelvin và Hermann von Helmholtz) có thể xảy ra khi biến dạng vận tốc xuất hiện trong một chất lỏng liên tục, hoặc khi có sự khác biệt tốc độ đầy đủ qua giao diện giữa hai chất lỏng. Một ví dụ là gió thổi trên một bề mặt nước, gió gây ra các chuyển động tương đối giữa các lớp phân tầng (nghĩa là, nước và không khí). Sự bất ổn định sẽ biểu hiện ở dạng sóng được tạo ra trên bề mặt nước. Các sóng này có thể xuất hiện trong nhiều chất lỏng khác nhau và đã được phát hiện trong các đám mây, các dải của Sao Thổ, sóng trong đại dương, và trong vầng hào quang của Mặt Trời[1]. Lý thuyết này có thể được sử dụng để dự đoán sự khởi đầu của sự bất ổn định và quá trình chuyển chiếp thành dòng chảy rối đối với các chất lỏng có mật độ khác nhau di chuyển ở tốc độ khác nhau. Helmholtz nghiên cứu các động lực học của hai dòng lưu chất có mật độ khác nhau khi có một xáo trộn nhỏ như một làn sóng được tạo ra tại ranh giới tiếp xúc giữa hai chất lỏng.

Đối với một số bước sóng đủ ngắn, nếu bỏ qua sức căng bề mặt, hai chất lỏng chuyển động song song với vận tốc và mật độ khác nhau sẽ sinh ra một bề mặt ranh giới không ổn định cho tất cả các mức vận tốc. Tuy nhiên, sự tồn tại của sức căng bề mặt làm ổn định sự bất ổn bước sóng ngắn, và sau đó, lý thuyết này dự đoán sự ổn định cho đến khi vật tốc đạt đến một ngưỡng. Lý thuyết với sức căng bề mặt bao gồm rộng rãi dự báo sự khởi đầu của sự hình thành sóng trong các trường hợp quan trọng của gió trên mặt nước.

Tổng quan lý thuyết và các khái niệm toán học

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Fluid dynamics predicts the onset of instability and transition to turbulent flow within fluids of different densities moving at different speeds.[3] If surface tension is ignored, two fluids in parallel motion with different velocities and densities yield an interface that is unstable to short-wavelength perturbations for all speeds. However, surface tension is able to stabilize the short wavelength instability up to a threshold velocity.

If the density and velocity vary continuously in space (with the lighter layers uppermost, so that the fluid is RT-stable), the dynamics of the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability is described by the Taylor–Goldstein equation: where denotes the Brunt–Väisälä frequency, U is the horizontal parallel velocity, k is the wave number, c is the eigenvalue parameter of the problem, is complex amplitude of the stream function. Its onset is given by the Richardson number . Typically the layer is unstable for . These effects are common in cloud layers. The study of this instability is applicable in plasma physics, for example in inertial confinement fusion and the plasma–beryllium interface. In situations where there is a state of static stability, evident by heavier fluids found below than the lower fluid, the Rayleigh-Taylor instability can be ignored as the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability is sufficient given the conditions.[cần giải thích]

Numerically, the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability is simulated in a temporal or a spatial approach. In the temporal approach, the flow is considered in a periodic (cyclic) box "moving" at mean speed (absolute instability). In the spatial approach, simulations mimic a lab experiment with natural inlet and outlet conditions (convective instability).

Tham khảo

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- ^ Fox, Karen C. “NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory Catches "Surfer" Waves on the Sun”. NASA-The Sun-Earth Connection: Heliophysics. NASA. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 20 tháng 11 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 26 tháng 3 năm 2012.

- ^ Sutherland, Scott (23 tháng 3 năm 2017). “Cloud Atlas leaps into 21st century with 12 new cloud types”. The Weather Network. Pelmorex Media. Truy cập ngày 24 tháng 3 năm 2017.

- ^ Drazin, P. G. (2003). Encyclopedia of Atmospheric Sciences. Elsevier Ltd. tr. 1068–1072. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-382225-3.00190-0.

GIẢM

20%

GIẢM

20%

GIẢM

31%

GIẢM

31%

GIẢM

20%

GIẢM

20%

GIẢM

49%

GIẢM

49%

GIẢM

40%

GIẢM

40%

GIẢM

13%

GIẢM

13%

![{\displaystyle (U-c)^{2}\left({d^{2}{\tilde {\phi }} \over dz^{2}}-k^{2}{\tilde {\phi }}\right)+\left[N^{2}-(U-c){d^{2}U \over dz^{2}}\right]{\tilde {\phi }}=0,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c6c95a25c4409c61a28f688c8f20f88f3ff49a5f)