Wiki Article

Jamaspa

Nguồn dữ liệu từ Wikipedia, hiển thị bởi DefZone.Net

| Jamaspa | |

|---|---|

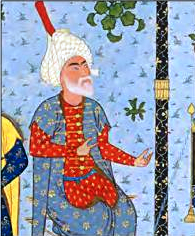

Illustration of Jamaspa in the Shahnameh | |

| In-universe information | |

| Affiliation | Vishtaspa |

| Nationality | Iranian |

Jamaspa (Avestan: 𐬬𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬁𐬯𐬞𐬀 Jāmāspa; Avestan pronunciation: [d̠ʒaːmaːspa]) is a figure from the Iranian national history, where he appears as an official at the court of Vishtaspa and overall important figure in the early history of Zoroastrianism.[1]

Name

[edit]The name Jamaspa is widely considered to be a contraction of tetrasyllabic jāma-aspa, an Avestan compound term, where the second word means aspa, i.e. horse. This term is also found in the names of people like Vishtaspa, Arjaspa and Lohraspa.[2] Since they all originate from the same story, it has been interpreted as an important element in their culture. However, the meaning of the first term is unclear.[1] One interpretation connects jāma- to Vedic kṣāmáh-, with the meaning burnt, singed.[3] On the other hand, Gershevitch proposed leading horses,[4] whereas Schwartz has argued for he who bridles horses.[5]

In the Avesta

[edit]In the Avesta, Jamaspa first appears in the Gathas with his brother Frashaoshtra, both from the clan of the Hvōgva.[6] He is described as a counsellor and chancellor of Vishtaspa, the patron of Zarathustra, and quickly converts to the new faith.[7] In the later texts found in the Young Avesta, Jamaspa also appears. In the Aban Yasht, he is grouped with people from the Gathas, and set apart from other, probably pre-Zoroastrian figures of the Iranian national tradition.[8] In the Frawardin Yasht, he is again praised jointly with Frashaoshtra and Vishtaspa.[1]

In later tradition

[edit]According to later tradition, it is Jamaspa, who aquires a leadership role in the Zoroastrian community after the death of Zarathustra and it is him who writes down his teachings in the Avesta.[7] He is a prominent figure in the Jamasp Namag (Story of Jamasp), also known as Ayatkar i Zamaspik (Memorial of Jamaspa).[9] This text discusses a number of topics framed as a dialogue between him and Vishtaspa.[10] He also appears in works like the Denkard, the Ayadgar i Zariran and the Shahnameh.[1]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Malandra 2008.

- ^ Yarshater 1983, p. 437.

- ^ Mayrhofer 1992, p. 430.

- ^ Gershevitch 1969, pp. 177 ff..

- ^ Schwartz 1975, p. 10.

- ^ Jackson 1965, p. 22.

- ^ a b Jackson 1965, p. 76.

- ^ Yarshater 1983, p. 413.

- ^ de Menasce 1983, p. 1194.

- ^ Boyce 1987.

Bibliography

[edit]- Boyce, Mary (1987). "Ayādgār Ī Jāmāspīg". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 126–127.

- Malandra, William W. (2008). "Jāmāspa". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XIV. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 456–457.

- de Menasce, Jean P. (1983). "Zoroastrian Pahlavi Writings". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3(2). Cambridge University Press.

- Gershevitch, Ilya (1969). "Amber at Persepolis". Studia classica et orientalia Antonino Pagliaro oblata. Vol. II. Roma: Herder. p. 981.

- Jackson, A. V. Williams (1965). The Prophet of Ancient Iran. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Mayrhofer, Manfred (1992). Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindoarischen - 1. Band. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universität. Archived from the original on 2020-04-10. Retrieved 2026-01-10.

- Schwartz, Martin (1975). "Proto-Indo-European √gīem-". Monumentum H. S. Nyberg. Acta Iranica. Tehran, Liège: Bibliothèque Pahlavi.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (1983). "Iranian National History". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3(1). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24693-4.