Wiki Article

Base and superstructure

Nguồn dữ liệu từ Wikipedia, hiển thị bởi DefZone.Net

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

| Outline |

Base and superstructure are concepts in Marxist theory that explain the relationship between a society's economic foundation and its other social forms. The base consists of the social relations of production—the economic structure of society—that people enter into to produce the necessities of life. The superstructure refers to the legal, political, and cultural realms, including institutions, ideologies, and forms of social consciousness, which arise on this base. The core proposition is that the economic base conditions or determines the overall character of the superstructure; while this relationship is not seen as a simple one-way causality, as the superstructure can also influence the base, the economic factor is considered determinant in the long run.

A central controversy in the scholarly interpretation of the concepts revolves around the distinction between Karl Marx's original, specific formulation and the later, expanded, all-inclusive version. Marx's primary formulation, most clearly stated in his 1859 Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, defined the superstructure restrictively as the "legal and political superstructure" that arises from the economic base, and distinguished it from the "definite forms of social consciousness" which correspond to it. This established an intrinsic, genetic link between the political and legal realm (the state) and the economic relations of production.

Following Marx's death, Friedrich Engels expanded the concept, particularly in his later works such as Anti-Dühring and his correspondence. He included ideological forms such as philosophy, religion, and art within the superstructure, creating a more heterogeneous and all-encompassing model. This panoramic version became the canonical interpretation within the Second International and later Soviet Marxism, where it was codified as a fundamental tenet of dialectical materialism. This expansion led to accusations of crude economic determinism and reductionism, prompting Engels and later Marxists like Georgi Plekhanov and Louis Althusser to introduce concepts such as "determination in the last instance", "relative autonomy", and "overdetermination" to account for the apparent independence of superstructural elements.

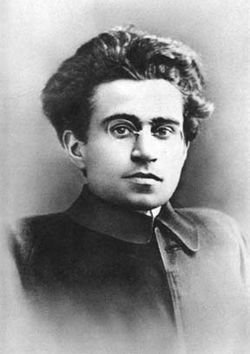

Many 20th-century Marxists, particularly those in the Western Marxist tradition like Antonio Gramsci, Georg Lukács, and Raymond Williams, expressed dissatisfaction with the rigid, stratified model. They developed alternative concepts such as hegemony and social totality to provide a more dynamic and interactive understanding of social formations, often critiquing or rejecting the base-superstructure model in its received form. Other recent theories propose that superstructures arise not as mere reflections but as solutions to contradictions within the base. To solve these problems, superstructures must have their own distinct systems of production, which grants them a degree of autonomy and can place them in conflict with the base. Scholar Dileep Edara argues that this entire trajectory of expansion and subsequent modification represents a "blunder" that obscures Marx's original intent, and that Marx's holistic paradigm was not the base-superstructure model but his theory of the mode of production.

Marx's original formulation

[edit]

The most authoritative and detailed statement by Karl Marx on the concepts of base and superstructure appears in the 1859 Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. This text is considered by many scholars to be the canonical formulation of historical materialism.[1] In this preface, Marx argues that the economic structure of society is the foundation upon which its political and legal institutions are built. He summarizes the "guiding principle" of his studies as follows:

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life.[2]

In this formulation, the concepts are precisely defined. The "base" (or Basis) is composed of the "totality of these relations of production". This refers to the class-based social relationships that people must enter into to produce and reproduce their material lives. Marx is explicit that the base does not include the "material forces of production" (technology, raw materials, etc.), a common point of misinterpretation in later accounts.[3]

The "superstructure" (or Überbau) is described specifically and exclusively as the "legal and political superstructure".[3] This formulation restricts the concept to the realm of the state and its legal apparatus. Marx differentiates this from the "definite forms of social consciousness" (ideology, religion, philosophy, etc.), which do not form part of the superstructure but are said to correspond to it.[3] This distinction is often overlooked in later, more expansive interpretations. The relationship between the base and the restricted superstructure is described as genetic and organic; the superstructure "arises" (erhebt sich) on the foundation. This implies that the existence of the political and legal sphere is intrinsically dependent on the class-based structure of the economic base. Political power, for Marx, is the organized power of one class for oppressing another, and it ceases to be political once class distinctions disappear.[4] Marx himself hinted at the importance of contradictions in explaining social consciousness, stating that it "must be explained from the contradictions of material life".[5] Furthermore, his language suggests an active process, arguing that a class "creates and forms" its superstructures from its material foundations, a more dynamic conception than the passive "reflection" model often attributed to later interpretations.[6]

This restricted version of the superstructure is consistently maintained by Marx in the works published during his lifetime. In a footnote in Volume 1 of Das Kapital (1867), he reiterates his 1859 formulation, referring to "the economic structure of society, is the real basis on which the juridical and political superstructure is raised".[7] In works like The German Ideology, Marx provides detailed analysis of how the state and law are not autonomous entities based on "will", but are rather the "power creating" expressions of material relations of production.[8] This core idea—that the state and its legal forms are rooted in and derive their existence from the specific economic relations of a society—is the central insight encapsulated in Marx's original base and superstructure metaphor.[9]

Expansion and transformation of the concept

[edit]The understanding of base and superstructure underwent a significant expansion after Marx's death, a development traced by scholar Dileep Edara as a "genealogy of heterogeneity" or a conceptual "blunder".[10] This transformation moved the concept from Marx's specific politico-legal formulation to an all-encompassing model that included a wide range of social phenomena.

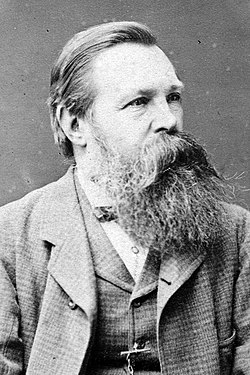

Friedrich Engels

[edit]

The origin of the expanded, panoramic version of the superstructure is largely found in the later works of Friedrich Engels. In popular and accessible texts like Anti-Dühring (1878) and Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1880), Engels redefined the superstructure to include not just legal and political institutions but also "the religious, philosophical, and other ideas of a given historical period".[11] In Anti-Dühring, he refers to the "ideological superstructure in the shape of philosophy, religion, art, etc."[12] This version, which grouped all non-economic aspects of society into a single superstructural category, became highly influential and was widely accepted as the standard Marxist position.[11]

This expanded model created theoretical problems, as it appeared to promote a crude economic determinism where culture and ideas were seen as mere passive reflections of the economic base. In his later letters, notably to Conrad Schmidt, Joseph Bloch, and Franz Mehring in the 1890s, Engels attempted to correct this "mechanistic" interpretation.[13] He introduced important qualifications, arguing that the economic element is the "ultimately determining factor in history" and not the only one.[14] He stressed the "interaction" of the various elements of the superstructure, which could in turn "exercise their influence upon the course of the historical struggles".[14] While intended as a refinement, these "corrective efforts" had the paradoxical effect of solidifying the heterogeneous version of the superstructure, as they were predicated on the assumption that culture, ideology, and other factors were indeed part of this superstructure.[14] In another attempt at explanation, Engels proposed that the state arises from the social division of labor. As society creates new "common functions", the people assigned to them develop their own interests and become an independent power, which, while generally following the trend of production, also reacts back upon it.[15]

Later analysts, such as RJ Robinson, have critiqued Engels's explanations as inadequate, arguing that they lack a coherent materialist or dialectical basis. Robinson contends that the concept of "relative autonomy" and the appeal to determination "in the last instance" function as assertions rather than explanations, failing to specify the actual mechanisms connecting the base and superstructure.[16]

Second International and Soviet Marxism

[edit]Engels's formulations were inherited and further developed by the leading theorists of the Second International. Figures like Georgi Plekhanov and Karl Kautsky adopted the all-inclusive model of the superstructure. Plekhanov, in particular, with his strong interest in art and culture, consistently placed these domains within the ideological superstructure. He developed the concept of social psychology as a mediating link between the economic base and the "higher" ideologies, further cementing the idea of a complex, multi-layered superstructure.[17]

This trajectory culminated in the official doctrine of Soviet Marxism under Joseph Stalin. Stalin's 1950 work, Marxism and the Problems of Linguistics, offered a definitive, though highly idiosyncratic, formulation. While arguing that language was neither base nor superstructure, he provided a canonical definition of what was: "The superstructure is the political, legal, religious, artistic, philosophical views of society and the political, legal and other institutions corresponding to them."[18] In a radical inversion of Marx's logic, Stalin suggested that ideological views precede and "provide" the corresponding institutions, rather than institutions arising from the base.[18] This view was enshrined in official texts like the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, which defined the superstructure as the "totality of the ideological relations, views, and institutions".[19] This formulation became the standard, unquestioned version in "official" Marxism and greatly influenced Marxist thought worldwide.[20]

Theoretical problems and debates

[edit]The expansion of the base and superstructure model from Marx's original formulation created a series of persistent theoretical problems that have preoccupied Marxist theory ever since. The all-encompassing version was widely criticized, both within and outside Marxism, for its apparent economic determinism and reductionism, where complex cultural phenomena were seen as simple "reflections" of the economy.[21] This led to several lines of debate and attempts at theoretical refinement.

One major response was the development of the eclectic "theory of factors", which became popular during the Second International. This theory viewed society as an interplay of various "factors"—economic, political, legal, religious, etc.—with the economic factor being the most important "in the last analysis". Theorists like Eduard Bernstein championed Engels's later letters as a move away from "absolutist interpretation" toward a more flexible model that accounted for the "multiplicity of the factors".[22] However, as critics like Antonio Labriola pointed out, this theory merely reified the different aspects of social life into abstract, independent forces, thereby losing Marx's sense of an integrated social totality.[23]

In the 20th century, Western Marxist thinkers proposed more sophisticated solutions. Louis Althusser, building on Engels's framework, developed the concepts of "relative autonomy" and "overdetermination". He argued that the different levels of the superstructure (political, ideological) have their own specific dynamics and histories, and are not simply reflections of the economic base. The economy determines the overall structure only "in the last instance", while historical events are "overdetermined" by a complex combination of contradictions from all levels.[24]

Other theorists rejected the stratified model more fundamentally. Georg Lukács, Karl Korsch, and Antonio Gramsci reclaimed the Hegelian concept of "totality", arguing that the decisive feature of Marxism was not the primacy of the economic but the "point of view of totality".[25] For them, the mechanical separation of society into a base and a superstructure was an undialectical distortion. Gramsci's concept of the "historical bloc" proposed a "dialectical unity of infrastructure and superstructures" in which the complex relations between economics, politics, and culture could be understood without resorting to a rigid, hierarchical model.[26] Similarly, the British cultural Marxists, most notably Raymond Williams and E. P. Thompson, largely repudiated the base-superstructure metaphor as "radically defective". Williams criticized it as a "rigid, abstract and static character" and instead advocated for seeing culture as a constitutive social process, a "whole way of life" that could not be relegated to a secondary, superstructural realm.[27]

Theories of contradiction and production

[edit]A 21st-century approach, articulated by RJ Robinson, attempts to provide a materialist and dialectical basis for the relationship by grounding it in the concept of contradiction. Robinson argues that superstructures arise from fundamental contradictions within the economic base which the base itself cannot resolve.[28] These contradictions can be of two types: shortcomings in the forces of production (the base is unable to produce a necessary resource, such as a skilled workforce or key infrastructure) and contradictions in the relations of production (the base's own class structure creates conflict, disorder, or exploitation that threatens its stability).[29] For example, capitalism's reliance on a literate, numerate, and compliant workforce—a force of production it cannot create through its own commodity-exchange mechanisms—necessitates the creation of a public education system as a superstructure.[30] Similarly, the need to manage dissent and ensure public order requires superstructures like the police and a legal system.[31] This idea that superstructures function to manage contradictions is not entirely new, with Terry Eagleton and Maurice Godelier having proposed similar arguments.[32]

To solve these problems, superstructures must develop their own distinct "systems of production". They cannot simply use the base's methods, because it is precisely the base's methods that failed to solve the problem.[33] Each superstructure thus has its own unique forces and relations of production—specialized knowledge, skills, and institutions—that differ from those of the economic base.[34] This distinct productive capacity is what gives superstructures their "relative autonomy" and allows them to function. It also explains their material reality: superstructures are not ethereal ideas but concrete institutions and practices that produce real effects, from legal judgments to educated citizens.[35]

This framework also posits a fundamental rivalry between base and superstructure. Because superstructures in a capitalist society are generally unprofitable (e.g., public healthcare does not generate profit for the capitalist class as a whole), there is a constant pressure from the base to reduce their cost, commercialize their functions, or re-assimilate them into the economic base through privatization. This struggle is referred to as "superstructure capture".[36]

Mode of production as an alternative paradigm

[edit]According to scholar Dileep Edara, many of the theoretical difficulties associated with the all-inclusive base-superstructure model are resolved by distinguishing it from what he identifies as Marx's true holistic paradigm: the theory of the mode of production.[37] While the base-superstructure metaphor is a structural model describing the specific genetic relationship between the economy and the state, the mode of production thesis is a praxiological model that encompasses the entire social totality as an articulated network of human practices.[38]

In Marx's 1859 Preface, the mode of production thesis is presented in a separate sentence: "The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life."[2] This thesis is not about a foundation supporting a structure, but about a central human activity—the way people produce their material existence—"conditioning" or determining the "general character" of all other social activities.[39] As Marx explains in a later text, "it is the mode in which they gained a livelihood that explains why here politics, and there Catholicism, played the chief part."[40] The mode of production thus determines the relative significance and specific articulation of all social spheres—including art, religion, and philosophy—within a given historical epoch. Unlike the static, layered imagery of the base-superstructure model, the mode of production thesis provides a dynamic and historicized framework for understanding the unique "social totality" of each society.[41]

The conflation of these two distinct theses has been a major source of confusion in Marxism.[42] Many interpreters, from Engels onward, have treated "mode of production" as a synonym for the "base", thereby collapsing the holistic paradigm into the more limited structural metaphor. This conceptual "prolapse" has had two major consequences: first, the base-superstructure model was incorrectly burdened with explaining all social phenomena, leading to its untenable expansion and the subsequent problems of reductionism; second, the unique insights of the mode of production thesis—particularly its emphasis on human activity (praxis) and the specific, articulated nature of each social formation—were lost.[37]

Several influential Marxist analyses, while formally using the language of base and superstructure, implicitly operate with the logic of the mode of production. For instance, Raymond Williams's focus on culture as a "social practice" and his theory of "social totality", or Fredric Jameson's analysis of postmodernism as the "cultural logic of late capitalism" (a new mode of production), are more consonant with the mode of production thesis.[43] By restoring the mode of production thesis to its central place and reinstating the base-superstructure metaphor in its original, restricted sense, it is argued that the theoretical rigour and methodological vitality of Marx's thought can be recovered.[44]

Applications of the theory

[edit]The abstract relationship between base and superstructure has been used to analyze a wide variety of concrete social formations.

Law

[edit]

One of the most developed applications of the base-superstructure model is in the study of law. According to this framework, the legal system functions as a superstructure that arises to resolve contradictions that the economic base cannot handle on its own, particularly the disputes and conflicts inherent in property relations and commodity exchange.[45] While the legal system appears to be an independent and neutral arbiter, its structure and doctrines are seen as ultimately shaped by the interests of the ruling class.[46]

The law's "relative autonomy" is crucial to its function. To maintain legitimacy and function effectively, the legal system must be perceived as separate from and superior to the purely economic interests of the base. It operates through its own "system of production", with specialized professionals (judges, lawyers), institutions (courts), and a unique language and set of procedures that translate raw economic conflicts into abstract legal terms.[47] This creates a "caesura" between the economic world and the legal one. However, this separation is ideological; the law's core function is to preserve the existing relations of production. As Engels noted, the "juristic form is... made everything and the economic content nothing", which serves to obscure the fact that the legal system is ultimately sanctioning and perpetuating the economic structure.[48] Concepts like "free and equal" exchange in contract law, for example, mask the underlying material inequality and exploitation of the wage-labor relationship.[49]

The family

[edit]

The family is another social structure frequently analyzed within the base-superstructure framework. The capitalist family, in its typical nuclear form, is shaped by the needs of the economic base. It serves two primary functions for capitalism: it reproduces labor-power by raising the next generation of workers and maintaining current ones, and it acts as a primary unit for the consumption of commodities, driving economic demand.[50] The family's small, dissociated structure facilitates the geographical and social mobility required by the capitalist labor market.[51]

However, the family is also in a contradictory relationship with capitalism. Its internal relations are not based on commodity exchange or wage labor; rather, they are based on kinship, personal relationships, and non-remunerated domestic labor.[52] In this sense, the family's own "system of production" is fundamentally opposed to the logic of the capitalist base. Capitalism constantly seeks to "prise loose" aspects of family life and turn them into marketable commodities, while simultaneously depending on the non-commodified care work that the family provides. This inherent tension grants the family its superstructural autonomy and makes its relationship with the economic base one of constant, dynamic conflict.[52]

Legacy and contemporary use

[edit]The concept of base and superstructure, particularly in its expanded, all-inclusive form, has had a profound and lasting legacy. Within Marxist theory, it continues to provoke what scholar Dileep Edara terms a "persistent ambivalence".[10] While few contemporary Marxists subscribe to a crude, mechanistic determinism, the terminology of base and superstructure remains a central part of the theoretical vocabulary, often employed with numerous qualifications about "mediation", "reciprocal influence", and "relative autonomy".[21] For some, like Terry Eagleton, the model remains an indispensable tool for understanding the determining role of the economy and for grounding a revolutionary politics.[53] For others, it is an "unhappy legacy" that should be discarded in favor of more dynamic concepts.[54]

The concepts have also been widely adopted, and adapted, in academic discourses outside of Marxism, particularly in sociology, cultural studies, and literary theory. A survey of contemporary academic journals reveals a vast and varied use of the terms, often in a "facile and fashionable" manner, detached from their original theoretical context.[55] In these uses, the superstructure can refer to almost any non-economic phenomenon, including kinship systems, mass media, elder care, hegemonic masculinity, or even language.[56] In a complete reversal of the original Marxist formulation, one can even find references to an "economic superstructure".[57] This widespread, often uncritical, application of the metaphor is frequently accompanied by a general antipathy towards its perceived determinism. It is common for writers to use the concept of superstructure as a way of designating a phenomenon as "secondary", "epiphenomenal", or "merely" a reflection of something more fundamental.[58] This paradoxical fate—where the concepts are simultaneously expanded to cover an endless range of phenomena while being disfavored for their reductive implications—characterizes their contemporary status.[55]

The concept is frequently invoked in political and social critiques of neoliberalism and globalization. For instance, commentators argue that neoliberal policies, driven by the logic of the capitalist base (profit maximization), seek to dismantle or re-commercialize key superstructures such as public health, education, and welfare systems.[59] The privatization of the National Health Service in the UK or the deficiencies of the American healthcare system are cited as examples of the base actively undermining the functions of a superstructure to the detriment of both society and, paradoxically, the long-term productivity of capital itself.[60] Similarly, international institutions like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have been accused of imposing "structural adjustment programmes" (the Washington Consensus) that subordinate the national superstructures of developing countries to the interests of global finance capital.[61]

See also

[edit]- False consciousness

- Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses

- Marx's theory of alienation

- Structural functionalism

References

[edit]- ^ Edara 2016, p. 65.

- ^ a b Edara 2016, p. 68.

- ^ a b c Edara 2016, p. 71.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 83, 216.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 58.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 59.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 223, 230.

- ^ a b Edara 2016, p. 17.

- ^ a b Edara 2016, p. 122.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 121.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 123.

- ^ a b c Edara 2016, p. 116.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 54.

- ^ Robinson 2023, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 140, 146.

- ^ a b Edara 2016, p. 193.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 196.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 197.

- ^ a b Edara 2016, p. 15.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 142.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 276, 285.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 263.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 264, 272.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 270, 302.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 16.

- ^ Robinson 2023, pp. 21–22, 34.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 8.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 34.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 72.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 83.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 84.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 80.

- ^ Robinson 2023, pp. 156, 160.

- ^ a b Edara 2016, p. 210.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 225, 78.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 238.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 237.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 313.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 219.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 248, 297, 347.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 248.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 188.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 186.

- ^ Robinson 2023, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 196.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 189.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 127.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 126.

- ^ a b Robinson 2023, p. 129.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 334.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 300.

- ^ a b Edara 2016, p. 50.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Edara 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Edara 2016, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 169.

- ^ Robinson 2023, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Robinson 2023, p. 170.

Works cited

[edit]- Edara, Dileep (2016). Biography of a Blunder: Base and Superstructure in Marx and Later. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-8810-3.

- Robinson, RJ (2023). Base and Superstructure: Understanding Marxism's Second Biggest Idea (eBook) (2nd ed.). putney:2. ISBN 978-1-838193-84-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)

Further reading

[edit]- Althusser, Louis and Balibar, Étienne. Reading Capital. London: Verso, 2009.

- Bottomore, Tom (ed). A Dictionary of Marxist Thought, 2nd ed. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 1991. 45–48.

- Calhoun, Craig (ed), Dictionary of the Social Sciences Oxford University Press (2002)

- Hall, Stuart. "Rethinking the Base and Superstructure Metaphor." Papers on Class, Hegemony and Party. Bloomfield, J., ed. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1977.

- Chris Harman. "Base and Superstructure". International Socialism 2:32, Summer 1986, pp. 3–44.

- Harvey, David. A Companion to Marx's Capital. London: Verso, 2010.

- Larrain, Jorge. Marxism and Ideology. Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Humanities Press, 1983.

- Lukács, Georg. History and Class Consciousness. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1972.

- Postone, Moishe. Time, Labour, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx's Critical Theory. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- R.J. Robinson. Base and Superstructure. Understanding Marxism's Second Biggest Idea. Alton: Putney2, 2023.

- Williams, Raymond. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.