Bộ gen

| Các phần chính trong |

| Di truyền học |

|---|

|

| Từ khoá cho trang |

|

| Lược sử và chủ đề |

| Phát minh |

Trong lĩnh vực sinh học phân tử và di truyền học, thuật ngữ bộ gen dùng để chỉ tất cả các vật chất di truyền chứa trong một cá thể sinh vật. Những vật chất di truyền này gồm DNA ở nhiễm sắc thể, DNA ngoài nhiễm sắc thể (như DNA vòng ở ti thể, ở lục lạp nếu có), cả các RNA (nếu là RNA virut), có thể mang thông tin di truyền ở vùng mã hóa hoặc không mã hóa.[1][2][3][4][5] Thuật ngữ này dịch từ nguyên gốc tiếng Anh là genome, cũng đã được dịch là hệ gen.[6] Môn khoa học chuyên nghiên cứu về bộ gen được gọi là hệ gen học (genomics). Nhiều kiến thức thuộc lĩnh vực này được đề cập ở tạp chí Genome Research.

Từ nguyên

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- Thuật ngữ genome được giáo sư người Đức là Hans Winkler, đề xuất vào năm 1920,[7] mà từ điển Oxford gợi ý rằng cái tên này là sự pha trộn giữa các từ gen và nhiễm sắc thể.[8][9]

- Tuy nhiên, bộ gen của một sinh vật bao gồm tất cả các vật chất mang thông tin di truyền, dù ở nhiễm sắc thể hay ở ngoài nhiễm sắc thể. Nhưng ở các sinh vật có nhiễm sắc thể (sinh vật có cấu tạo tế bào), có tác giả gọi axit nucleic ở nhiễm sắc thể như là bộ gen chính, còn ở ngoài là bộ gen phụ. Chẳng hạn ở người, mỗi cá thể có bộ nhiễm sắc thể lưỡng bội là 2n = 46, thì tập hợp tất cả các DNA ở mọi nhiễm sắc thể tạo nên bộ gen chính, còn gọi là bộ gen lưỡng bội; còn lại các gen trong ti thể, ở ngoài nhân được coi là phụ, mặc dù có tầm quan trọng nhất định và đột biến có thể gây bệnh, như một bệnh gây động kinh di truyền theo dòng mẹ.[3][10]

Bộ gen virut

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Bộ gen virut có thể có DNA hoặc RNA tùy loại.

- Các bệnh như đậu mùa, herpes và thủy đậu là do các virut DNA gây ra: bộ gen của chúng là phân tử DNA.

- Các bệnh như AIDS và Covid-19 là do virut RNA gây ra: bộ gen của chúng là RNA. Khi chúng xâm nhiễm vào vật chủ (người, dơi), phân tử RNA sẽ được enzym phiên mã ngược tạo nên DNA bổ sung của chúng, rồi từ đó nhân đôi thành DNA hai mạch chèn vào nhiễm sắc thể của vật chủ.

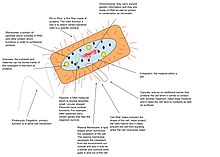

Bộ gen nhân sơ

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Nhân sơ (Prokaryotes) có cấu tạo đơn bào, nhưng bộ gen của chúng được phân biệt thành hai phần: hầu hết các gen phân bố ở một phân tử DNA vòng lớn gọi là nhiễm sắc thể nhân sơ (viết tắt: DNA-NST), còn lại phân bố ở các plasmit có số lượng rất không ổn định.[14][15][16][17]

Đặc điểm một số bộ gen

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Dưới đây là bảng giới thiệu một số bộ gen đại diện.

| Organism type | Organism | Genome size | Approx. no. of genes | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | Porcine circovirus type 1 | 1,759 | 1.8 kB | Smallest viruses replicating autonomously in eukaryotic cells.[18] | |

| Virus | Bacteriophage MS2 | 3,569 | 3.5 kB | First sequenced RNA-genome[19] | |

| Virus | SV40 | 5,224 | 5.2 kB | [20] | |

| Virus | Phage Φ-X174 | 5,386 | 5.4 kB | First sequenced DNA-genome[21] | |

| Virus | HIV | 9,749 | 9.7 kB | [22] | |

| Virus | Phage λ | 48,502 | 48.5 kB | Often used as a vector for the cloning of recombinant DNA. | |

| Virus | Megavirus | 1,259,197 | 1.3 MB | Until 2013 the largest known viral genome.[26] | |

| Virus | Pandoravirus salinus | 2,470,000 | 2.47 MB | Largest known viral genome.[27] | |

| Eukaryotic organelle | Human mitochondrion | 16,569 | 16.6 kB | [28] | |

| Bacterium | Nasuia deltocephalinicola (strain NAS-ALF) | 112,091 | 112 kB | 137 | Smallest known non-viral genome. Symbiont of leafhoppers.[29] |

| Bacterium | Carsonella ruddii | 159,662 | 160 kB | An endosymbiont of psyllid insects | |

| Bacterium | Buchnera aphidicola | 600,000 | 600 kB | An endosymbiont of aphids[30] | |

| Bacterium | Wigglesworthia glossinidia | 700,000 | 700Kb | A symbiont in the gut of the tsetse fly | |

| Bacterium – cyanobacterium | Prochlorococcus spp. (1.7 Mb) | 1,700,000 | 1.7 MB | 1,884 | Smallest known cyanobacterium genome. One of the primary photosynthesizers on Earth.[31][32] |

| Bacterium | Haemophilus influenzae | 1,830,000 | 1.8 MB | First genome of a living organism sequenced, July 1995[33] | |

| Bacterium | Escherichia coli | 4,600,000 | 4.6 MB | 4,288 | [34] |

| Bacterium – cyanobacterium | Nostoc punctiforme | 9,000,000 | 9 MB | 7,432 | 7432 open reading frames[35] |

| Bacterium | Solibacter usitatus (strain Ellin 6076) | 9,970,000 | 10 MB | [36] | |

| Amoeboid | Polychaos dubium ("Amoeba" dubia) | 670,000,000,000 | 670 GB | Largest known genome.[37] (Disputed)[38] | |

| Plant | Genlisea tuberosa | 61,000,000 | 61 MB | Smallest recorded flowering plant genome, 2014.[39] | |

| Plant | Arabidopsis thaliana | 135,000,000[40] | 135 MB | 27,655[41] | First plant genome sequenced, December 2000.[42] |

| Plant | Populus trichocarpa | 480,000,000 | 480 MB | 73,013 | First tree genome sequenced, September 2006[43] |

| Plant | Fritillaria assyriaca | 130,000,000,000 | 130 GB | ||

| Plant | Paris japonica (Japanese-native, pale-petal) | 150,000,000,000 | 150 GB | Largest plant genome known[44] | |

| Plant – moss | Physcomitrella patens | 480,000,000 | 480 MB | First genome of a bryophyte sequenced, January 2008.[45] | |

| Fungus – yeast | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 12,100,000 | 12.1 MB | 6,294 | First eukaryotic genome sequenced, 1996[46] |

| Fungus | Aspergillus nidulans | 30,000,000 | 30 MB | 9,541 | [47] |

| Nematode | Pratylenchus coffeae | 20,000,000 | 20 MB | [48] Smallest animal genome known[49] | |

| Nematode | Caenorhabditis elegans | 100,300,000 | 100 MB | 19,000 | First multicellular animal genome sequenced, December 1998[50] |

| Insect | Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) | 175,000,000 | 175 MB | 13,600 | Size variation based on strain (175-180Mb; standard y w strain is 175Mb)[51] |

| Insect | Apis mellifera (honey bee) | 236,000,000 | 236 MB | 10,157 | [52] |

| Insect | Bombyx mori (silk moth) | 432,000,000 | 432 MB | 14,623 | 14,623 predicted genes[53] |

| Insect | Solenopsis invicta (fire ant) | 480,000,000 | 480 MB | 16,569 | [54] |

| Mammal | Mus musculus | 2,700,000,000 | 2.7 GB | 20,210 | [55] |

| Mammal | Pan paniscus | 3,286,640,000 | 3.3 GB | 20,000 | Bonobo - estimated genome size 3.29 billion bp[56] |

| Mammal | Homo sapiens | 3,000,000,000 | 3 GB | 20,000 | Homo sapiens genome size estimated at 3.2 Gbp in 2001[57][58] Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome[59] |

| Bird | Gallus gallus | 1,043,000,000 | 1.0 GB | 20,000 | [60] |

| Fish | Tetraodon nigroviridis (type of puffer fish) | 385,000,000 | 390 MB | Smallest vertebrate genome known estimated to be 340 Mb[61][62] – 385 Mb.[63] | |

| Fish | Protopterus aethiopicus (marbled lungfish) | 130,000,000,000 | 130 GB | Largest vertebrate genome known | |

Xem thêm

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- Bacterial genome size

- Cryoconservation of animal genetic resources

- Genome Browser

- Genome Compiler

- Genome topology

- Genome-wide association study

- List of sequenced animal genomes

- List of sequenced archaeal genomes

- List of sequenced bacterial genomes

- List of sequenced eukaryotic genomes

- List of sequenced fungi genomes

- List of sequenced plant genomes

- List of sequenced plastomes

- List of sequenced protist genomes

- Metagenomics

- Microbiome

- Molecular epidemiology

- Molecular pathological epidemiology

- Molecular pathology

- Nucleic acid sequence

- Pan-genome

- Precision medicine

- Regulator gene

- Sequenceome

- Whole genome sequencing

Tham khảo

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- Benfey P, Protopapas AD (2004). Essentials of Genomics. Prentice Hall.

- Brown TA (2002). Genomes 2. Oxford: Bios Scientific Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85996-029-5.

- Gibson G, Muse SV (2004). A Primer of Genome Science . Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Assoc. ISBN 978-0-87893-234-4.

- Gregory TR (2005). The Evolution of the Genome. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-301463-4.

- Reece RJ (2004). Analysis of Genes and Genomes. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-84379-6.

- Saccone C, Pesole G (2003). Handbook of Comparative Genomics. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-39128-9.

- Werner E (tháng 12 năm 2003). “In silico multicellular systems biology and minimal genomes”. Drug Discovery Today. 8 (24): 1121–27. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02918-0. PMID 14678738.

Hình ảnh

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Nguồn trích dẫn

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- ^ Campbell và cộng sự: "Sinh học" - Nhà xuất bản Giáo dục, 2010

- ^ “genome”.

- ^ a b Roth, Stephanie Clare (ngày 1 tháng 7 năm 2019). “What is genomic medicine?”. Journal of the Medical Library Association. University Library System, University of Pittsburgh. 107 (3). doi:10.5195/jmla.2019.604. ISSN 1558-9439. PMC 6579593. PMID 31258451.

- ^ Brosius, J (2009), “The Fragmented Gene”, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1178 (1): 186–93, Bibcode:2009NYASA1178..186B, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05004.x, PMID 19845638, S2CID 8279434

- ^ Ridley M (2006). Genome: the autobiography of a species in 23 chapters (PDF). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-019497-0. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 24 tháng 10 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 5 năm 2016.

- ^ Phạm Thành Hổ: "Sinh học" - Nhà xuất bản Giáo dục, 1998

- ^ Winkler HL (1920). Verbreitung und Ursache der Parthenogenesis im Pflanzen- und Tierreiche. Jena: Verlag Fischer.

- ^ “definition of Genome in Oxford dictionary”. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 3 tháng 3 năm 2016. Truy cập ngày 25 tháng 3 năm 2014.

- ^ Lederberg J, McCray AT (2001). “'Ome Sweet 'Omics – A Genealogical Treasury of Words” (PDF). The Scientist. 15 (7). Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 29 tháng 9 năm 2006.

- ^ "Sinh học 12" - Nhà xuất bản Giáo dục, 2019

- ^ Gelderblom, Hans R. (1996). Medical Microbiology (ấn bản thứ 4). Galveston, TX: The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

- ^ Urry, Lisa A. (2016). Campbell Biology: seventh edition. New York: Hoboken: Pearson Higher Education. tr. 403–404. ISBN 0134093410.

- ^ Urry, Lisa A (2016). Campbell Biology: seventh edition. New York: Hoboken: Pearson Higher Education. tr. 403–404. ISBN 0134093410.

- ^ Samson RY, Bell SD (2014). “Archaeal chromosome biology”. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology. 24 (5–6): 420–27. doi:10.1159/000368854. PMC 5175462. PMID 25732343.

- ^ Chaconas G, Chen CW (2005). “Replication of Linear Bacterial Chromosomes: No Longer Going Around in Circles”. The Bacterial Chromosome: 525–540. doi:10.1128/9781555817640.ch29. ISBN 9781555812324.

- ^ “Bacterial Chromosomes”. Microbial Genetics. 2002.

- ^ Koonin EV, Wolf YI (tháng 7 năm 2010). “Constraints and plasticity in genome and molecular-phenome evolution”. Nature Reviews. Genetics. 11 (7): 487–98. doi:10.1038/nrg2810. PMC 3273317. PMID 20548290.

- ^ Mankertz P (2008). “Molecular Biology of Porcine Circoviruses”. Animal Viruses: Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-22-6.

- ^ Fiers W, Contreras R, Duerinck F, Haegeman G, Iserentant D, Merregaert J, Min Jou W, Molemans F, Raeymaekers A, Van den Berghe A, Volckaert G, Ysebaert M (tháng 4 năm 1976). “Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage MS2 RNA: primary and secondary structure of the replicase gene”. Nature. 260 (5551): 500–07. Bibcode:1976Natur.260..500F. doi:10.1038/260500a0. PMID 1264203. S2CID 4289674.

- ^ Fiers W, Contreras R, Haegemann G, Rogiers R, Van de Voorde A, Van Heuverswyn H, Van Herreweghe J, Volckaert G, Ysebaert M (tháng 5 năm 1978). “Complete nucleotide sequence of SV40 DNA”. Nature. 273 (5658): 113–20. Bibcode:1978Natur.273..113F. doi:10.1038/273113a0. PMID 205802. S2CID 1634424.

- ^ Sanger F, Air GM, Barrell BG, Brown NL, Coulson AR, Fiddes CA, Hutchison CA, Slocombe PM, Smith M (tháng 2 năm 1977). “Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage phi X174 DNA”. Nature. 265 (5596): 687–95. Bibcode:1977Natur.265..687S. doi:10.1038/265687a0. PMID 870828. S2CID 4206886.

- ^ “Virology – Human Immunodeficiency Virus And Aids, Structure: The Genome And Proteins Of HIV”. Pathmicro.med.sc.edu. ngày 1 tháng 7 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 27 tháng 1 năm 2011.

- ^ Thomason L, Court DL, Bubunenko M, Costantino N, Wilson H, Datta S, Oppenheim A (tháng 4 năm 2007). “Recombineering: genetic engineering in bacteria using homologous recombination”. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Chapter 1: Unit 1.16. doi:10.1002/0471142727.mb0116s78. ISBN 978-0-471-14272-0. PMID 18265390. S2CID 490362.

- ^ Court DL, Oppenheim AB, Adhya SL (tháng 1 năm 2007). “A new look at bacteriophage lambda genetic networks”. Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (2): 298–304. doi:10.1128/JB.01215-06. PMC 1797383. PMID 17085553.

- ^ Sanger F, Coulson AR, Hong GF, Hill DF, Petersen GB (tháng 12 năm 1982). “Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage lambda DNA”. Journal of Molecular Biology. 162 (4): 729–73. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(82)90546-0. PMID 6221115.

- ^ Legendre M, Arslan D, Abergel C, Claverie JM (tháng 1 năm 2012). “Genomics of Megavirus and the elusive fourth domain of Life”. Communicative & Integrative Biology. 5 (1): 102–06. doi:10.4161/cib.18624. PMC 3291303. PMID 22482024.

- ^ Philippe N, Legendre M, Doutre G, Couté Y, Poirot O, Lescot M, Arslan D, Seltzer V, Bertaux L, Bruley C, Garin J, Claverie JM, Abergel C (tháng 7 năm 2013). “Pandoraviruses: amoeba viruses with genomes up to 2.5 Mb reaching that of parasitic eukaryotes” (PDF). Science. 341 (6143): 281–86. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..281P. doi:10.1126/science.1239181. PMID 23869018. S2CID 16877147.

- ^ Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrell BG, de Bruijn MH, Coulson AR, Drouin J, Eperon IC, Nierlich DP, Roe BA, Sanger F, Schreier PH, Smith AJ, Staden R, Young IG (tháng 4 năm 1981). “Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome”. Nature. 290 (5806): 457–65. Bibcode:1981Natur.290..457A. doi:10.1038/290457a0. PMID 7219534. S2CID 4355527.

- ^ Bennett GM, Moran NA (ngày 5 tháng 8 năm 2013). “Small, smaller, smallest: the origins and evolution of ancient dual symbioses in a Phloem-feeding insect”. Genome Biology and Evolution. 5 (9): 1675–88. doi:10.1093/gbe/evt118. PMC 3787670. PMID 23918810.

- ^ Shigenobu S, Watanabe H, Hattori M, Sakaki Y, Ishikawa H (tháng 9 năm 2000). “Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS”. Nature. 407 (6800): 81–86. Bibcode:2000Natur.407...81S. doi:10.1038/35024074. PMID 10993077.

- ^ Rocap G, Larimer FW, Lamerdin J, Malfatti S, Chain P, Ahlgren NA, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 8 năm 2003). “Genome divergence in two Prochlorococcus ecotypes reflects oceanic niche differentiation”. Nature. 424 (6952): 1042–47. Bibcode:2003Natur.424.1042R. doi:10.1038/nature01947. PMID 12917642. S2CID 4344597.

- ^ Dufresne A, Salanoubat M, Partensky F, Artiguenave F, Axmann IM, Barbe V, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 8 năm 2003). “Genome sequence of the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus marinus SS120, a nearly minimal oxyphototrophic genome”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (17): 10020–25. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10010020D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1733211100. PMC 187748. PMID 12917486.

- ^ Fleischmann RD, Adams MD, White O, Clayton RA, Kirkness EF, Kerlavage AR, Bult CJ, Tomb JF, Dougherty BA, Merrick JM (tháng 7 năm 1995). “Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd”. Science. 269 (5223): 496–512. Bibcode:1995Sci...269..496F. doi:10.1126/science.7542800. PMID 7542800. S2CID 10423613.

- ^ Blattner FR, Plunkett G, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 9 năm 1997). “The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12”. Science. 277 (5331): 1453–62. doi:10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. PMID 9278503.

- ^ Meeks JC, Elhai J, Thiel T, Potts M, Larimer F, Lamerdin J, Predki P, Atlas R (2001). “An overview of the genome of Nostoc punctiforme, a multicellular, symbiotic cyanobacterium”. Photosynthesis Research. 70 (1): 85–106. doi:10.1023/A:1013840025518. PMID 16228364. S2CID 8752382.

- ^ Challacombe JF, Eichorst SA, Hauser L, Land M, Xie G, Kuske CR (ngày 15 tháng 9 năm 2011). Steinke D (biên tập). “Biological consequences of ancient gene acquisition and duplication in the large genome of Candidatus Solibacter usitatus Ellin6076”. PLOS ONE. 6 (9): e24882. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...624882C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024882. PMC 3174227. PMID 21949776.

- ^ Parfrey LW, Lahr DJ, Katz LA (tháng 4 năm 2008). “The dynamic nature of eukaryotic genomes”. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 25 (4): 787–94. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn032. PMC 2933061. PMID 18258610.

- ^ ScienceShot: Biggest Genome Ever Lưu trữ 2010-10-11 tại Wayback Machine, comments: "The measurement for Amoeba dubia and other protozoa which have been reported to have very large genomes were made in the 1960s using a rough biochemical approach which is now considered to be an unreliable method for accurate genome size determinations."

- ^ Fleischmann A, Michael TP, Rivadavia F, Sousa A, Wang W, Temsch EM, Greilhuber J, Müller KF, Heubl G (tháng 12 năm 2014). “Evolution of genome size and chromosome number in the carnivorous plant genus Genlisea (Lentibulariaceae), with a new estimate of the minimum genome size in angiosperms”. Annals of Botany. 114 (8): 1651–63. doi:10.1093/aob/mcu189. PMC 4649684. PMID 25274549.

- ^ “Genome Assembly”. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR).

- ^ “Details - Arabidopsis thaliana - Ensembl Genomes 40”. plants.ensembl.org.

- ^ Greilhuber J, Borsch T, Müller K, Worberg A, Porembski S, Barthlott W (tháng 11 năm 2006). “Smallest angiosperm genomes found in lentibulariaceae, with chromosomes of bacterial size”. Plant Biology. 8 (6): 770–77. doi:10.1055/s-2006-924101. PMID 17203433.

- ^ Tuskan GA, Difazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 9 năm 2006). “The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray)” (PDF). Science. 313 (5793): 1596–604. Bibcode:2006Sci...313.1596T. doi:10.1126/science.1128691. PMID 16973872. S2CID 7717980.

- ^ Pellicer J, Fay MF, Leitch IJ (ngày 15 tháng 9 năm 2010). “The largest eukaryotic genome of them all?”. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 164 (1): 10–15. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2010.01072.x.

- ^ Lang D, Zimmer AD, Rensing SA, Reski R (tháng 10 năm 2008). “Exploring plant biodiversity: the Physcomitrella genome and beyond”. Trends in Plant Science. 13 (10): 542–49. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2008.07.002. PMID 18762443.

- ^ “Saccharomyces Genome Database”. Yeastgenome.org. Truy cập ngày 27 tháng 1 năm 2011.

- ^ Galagan JE, Calvo SE, Cuomo C, Ma LJ, Wortman JR, Batzoglou S, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 12 năm 2005). “Sequencing of Aspergillus nidulans and comparative analysis with A. fumigatus and A. oryzae”. Nature. 438 (7071): 1105–15. Bibcode:2005Natur.438.1105G. doi:10.1038/nature04341. PMID 16372000.

- ^ Leroy S, Bouamer S, Morand S, Fargette M (2007). “Genome size of plant-parasitic nematodes”. Nematology. 9 (3): 449–50. doi:10.1163/156854107781352089.

- ^ Gregory TR (2005). “Animal Genome Size Database”. Gregory, T.R. (2016). Animal Genome Size Database.

- ^ The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium (tháng 12 năm 1998). “Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology”. Science. 282 (5396): 2012–18. Bibcode:1998Sci...282.2012.. doi:10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. PMID 9851916. S2CID 16873716.

- ^ Ellis LL, Huang W, Quinn AM, Ahuja A, Alfrejd B, Gomez FE, Hjelmen CE, Moore KL, Mackay TF, Johnston JS, Tarone AM (tháng 7 năm 2014). “Intrapopulation genome size variation in D. melanogaster reflects life history variation and plasticity”. PLOS Genetics. 10 (7): e1004522. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004522. PMC 4109859. PMID 25057905.

- ^ Honeybee Genome Sequencing Consortium (tháng 10 năm 2006). “Insights into social insects from the genome of the honeybee Apis mellifera”. Nature. 443 (7114): 931–49. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..931T. doi:10.1038/nature05260. PMC 2048586. PMID 17073008.

- ^ The International Silkworm Genome (tháng 12 năm 2008). “The genome of a lepidopteran model insect, the silkworm Bombyx mori”. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 38 (12): 1036–45. doi:10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.11.004. PMID 19121390.

- ^ Wurm Y, Wang J, Riba-Grognuz O, Corona M, Nygaard S, Hunt BG, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 4 năm 2011). “The genome of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (14): 5679–84. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5679W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009690108. PMC 3078418. PMID 21282665.

- ^ Church DM, Goodstadt L, Hillier LW, Zody MC, Goldstein S, She X, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 5 năm 2009). Roberts RJ (biên tập). “Lineage-specific biology revealed by a finished genome assembly of the mouse”. PLOS Biology. 7 (5): e1000112. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000112. PMC 2680341. PMID 19468303.

- ^ “Pan paniscus (pygmy chimpanzee)”. nih.gov. Truy cập ngày 30 tháng 6 năm 2016.

- ^ Eric Lander; và đồng nghiệp (15 tháng 2 năm 2001). “Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome”. Nature. 409 (6822): 860–921. doi:10.1038/35057062. PMID 11237011. Table 8.

- ^ “Functional and Comparative Genomics Fact Sheet”. Ornl.gov. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 20 tháng 9 năm 2008.

- ^ Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 2 năm 2001). “The sequence of the human genome”. Science. 291 (5507): 1304–51. Bibcode:2001Sci...291.1304V. doi:10.1126/science.1058040. PMID 11181995.

- ^ International Chicken Genome Sequencing Consortium (tháng 12 năm 2004). “Sequence and comparative analysis of the chicken genome provide unique perspectives on vertebrate evolution”. Nature (bằng tiếng Anh). 432 (7018): 695–716. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..695C. doi:10.1038/nature03154. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15592404.

- ^ Roest Crollius H, Jaillon O, Dasilva C, Ozouf-Costaz C, Fizames C, Fischer C, Bouneau L, Billault A, Quetier F, Saurin W, Bernot A, Weissenbach J (tháng 7 năm 2000). “Characterization and repeat analysis of the compact genome of the freshwater pufferfish Tetraodon nigroviridis”. Genome Research. 10 (7): 939–49. doi:10.1101/gr.10.7.939. PMC 310905. PMID 10899143.

- ^ Jaillon O, Aury JM, Brunet F, Petit JL, Stange-Thomann N, Mauceli E, và đồng nghiệp (tháng 10 năm 2004). “Genome duplication in the teleost fish Tetraodon nigroviridis reveals the early vertebrate proto-karyotype”. Nature. 431 (7011): 946–57. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..946J. doi:10.1038/nature03025. PMID 15496914.

- ^ “Tetraodon Project Information”. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 26 tháng 9 năm 2012. Truy cập ngày 17 tháng 10 năm 2012.

Liên kết ngoài

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- UCSC Genome Browser – view the genome and annotations for more than 80 organisms.

- genomecenter.howard.edu

- Build a DNA Molecule

- Some comparative genome sizes

- DNA Interactive: The History of DNA Science

- DNA From The Beginning

- All About The Human Genome Project—from Genome.gov

- Animal genome size database

- Plant genome size database

- GOLD:Genomes OnLine Database

- The Genome News Network

- NCBI Entrez Genome Project database

- NCBI Genome Primer

- GeneCards—an integrated database of human genes

- BBC News – Final genome 'chapter' published

- IMG (The Integrated Microbial Genomes system)—for genome analysis by the DOE-JGI

- GeKnome Technologies Next-Gen Sequencing Data Analysis—next-generation sequencing data analysis for Illumina and 454 Service from GeKnome Technologies.

GIẢM

30%

GIẢM

30%

GIẢM

40%

GIẢM

40%

GIẢM

9%

GIẢM

9%

GIẢM

34%

GIẢM

34%

![[Review Sách] “Nuôi con bằng trái tim tỉnh thức” và “Hiện diện bên con”](https://down-bs-vn.img.susercontent.com/sg-11134201-7rcei-lt3s6wfwhy3qa4.webp) GIẢM

15%

GIẢM

15%

GIẢM

15%

GIẢM

15%