Wiki Article

2012 VP113

Nguồn dữ liệu từ Wikipedia, hiển thị bởi DefZone.Net

2012 VP113 imaged by the Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope on 9 October 2021 | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | |

| Discovery site | Cerro Tololo Obs. |

| Discovery date | 5 November 2012 |

| Designations | |

| 2012 VP113 | |

| Biden (nickname) | |

| Orbital characteristics (barycentric)[4] | |

| Epoch 5 May 2025 (JD 2460800.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 3[2] | |

| Observation arc | 16.94 yr (6,187 d) |

| Earliest precovery date | 19 September 2007 |

| Aphelion | 444.1 AU |

| Perihelion | 80.52 AU |

| 262.3 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.6931 |

| 4,246 yr[4] | |

| 24.05° | |

| 0° 0m 0.836s / day | |

| Inclination | 24.0563°±0.006° |

| 90.80° | |

| ≈ September 1979[5] | |

| 293.90° | |

| Known satellites | 0 |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 450 km (calc. for albedo 0.15)[6] | |

| |

| 23.5[7] | |

| 4.05[2] | |

2012 VP113 is a trans-Neptunian object (TNO) orbiting the Sun on an extremely wide elliptical orbit. It is classified as a sednoid because its orbit never comes closer than 80.5 AU (12.04 billion km; 7.48 billion mi) from the Sun, which is far enough away from the giant planets that their gravitational influence cannot affect the object's orbit noticeably. It was discovered on 5 November 2012 at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, by American astronomers Scott Sheppard and Chad Trujillo, who nicknamed the object "Biden" because of its "VP" abbreviation.[8] The discovery was announced on 26 March 2014.[6][8] The object's size has not been measured, but its brightness suggests it is around 450 km (280 mi) in diameter.[6][9] 2012 VP113 has a reddish color similar to many other TNOs.[6]

2012 VP113 has not yet been imaged by high-resolution telescopes, so it has no known moons.[10] The Hubble Space Telescope is planned to image 2012 VP113 in 2026, which should determine if it has significantly sized moons.[10]

History

[edit]Discovery

[edit]2012 VP113 was first reported to have been observed on 5 November 2012[1] with NOAO's 4-meter Víctor M. Blanco Telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory.[11] Carnegie's 6.5-meter Magellan telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile was used to determine its orbit and surface properties.[11]

Before being announced to the public, 2012 VP113 was only tracked by Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (807) and Las Campanas Observatory (304).[12]

2012 VP113 had previously been observed (but not reported) as early as September 2007.[12]

Nickname

[edit]2012 VP113 was abbreviated "VP" and nicknamed "Biden" by the discovery team, after Joe Biden who was then the vice president ("VP") of the United States in 2012.[8]

Physical characteristics

[edit]2012 VP113 has an absolute magnitude of 4.0,[12] which means it may be large enough to be a dwarf planet.[13] The diameter and geometric albedo of 2012 VP113 has not been measured.[6][9] If 2012 VP113 has a moderate geometric albedo of 15% (typical of TNOs), its diameter would be around 450 km (280 mi).[6] A wider range of albedos gives a possible diameter range of 300–1,000 km (190–620 mi).[9] It is expected to be about half the size of Sedna and similar in size to Huya.[9] Its surface is moderately red in color, resulting from chemical changes produced by the effect of radiation on frozen water, methane, and carbon dioxide.[14] This optical color is consistent with formation in the gas-giant region and not the classical Kuiper belt, which is dominated by ultra-red colored objects.[6]

Orbit and classification

[edit]

2012 VP113 has the farthest perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) of all known minor planets and all known objects in the Solar System as of 2025[update], greater than Sedna's.[15] Though its perihelion is farther, 2012 VP113 has an aphelion only about half of Sedna's. It is the second discovered sednoid, with a semi-major axis beyond 150 AU and a perihelion greater than 50 AU. The similarity of the orbit of 2012 VP113 to other known extreme trans-Neptunian objects led Scott Sheppard and Chad Trujillo to suggest that an undiscovered object, Planet Nine, in the outer Solar System is shepherding these distant objects into similar type orbits.[6]

Its last perihelion was within a couple months of September 1979.[5] The paucity of bodies with perihelia at 50–75 AU appears not to be an observational artifact.[6]

It is possibly a member of a hypothesized Hills cloud.[9][11][16] It has a perihelion, argument of perihelion, and current position in the sky similar to those of Sedna.[9] In fact, all known Solar System bodies with semi-major axes over 150 AU and perihelia greater than Neptune's have arguments of perihelion clustered near 340°±55°.[6] This could indicate a similar formation mechanism for these bodies.[6] (148209) 2000 CR105 was the first such object discovered.

It is currently unknown how 2012 VP113 acquired a perihelion distance beyond the Kuiper belt. The characteristics of its orbit, like those of Sedna's, have been explained as possibly created by a passing star or a trans-Neptunian planet of several Earth masses hundreds of astronomical units from the Sun.[17] The orbital architecture of the trans-Plutonian region may signal the presence of more than one planet.[18][19] 2012 VP113 could even be captured from another planetary system.[13] However, it is considered more likely that the perihelion of 2012 VP113 was raised by multiple interactions within the crowded confines of the open star cluster in which the Sun formed.[9]

-

Simulated view showing the orbit of 2012 VP113

-

2012 VP113 orbit in white with hypothetical Planet Nine

-

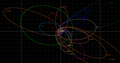

The orbits of known distant objects with large aphelion distances over 200 AU

See also

[edit]- List of Solar System objects most distant from the Sun

- 90377 Sedna – first sednoid discovered

- 541132 Leleākūhonua – third sednoid discovered

- List of hyperbolic comets

- List of possible dwarf planets

- Other large aphelion objects

- (668643) 2012 DR30 (15–2880 AU)

- 2005 VX3 (4–1630 AU)

- (709487) 2013 BL76 (8–1870 AU)

- 2014 FE72 (36–2680 AU)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "MPEC 2014-F40 : 2012 VP113". IAU Minor Planet Center. 26 March 2014. (K12VB3P)

- ^ a b c "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: (2012 VP113)" (3 December 2021 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ Johnston, Wm. Robert (7 October 2018). "List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects". Johnston's Archive. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b "JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris for (2012 VP113) at epoch JD 2460800.5". JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 15 July 2025. Solution using the Solar System Barycenter. Ephemeris Type: Elements and Center: @0)

- ^ a b "Horizons Batch for 2012 VP113 on 1979-Sep-28" (Perihelion occurs when rdot flips from negative to positive). JPL Horizons. Retrieved 21 June 2022. (JPL#9, Soln.date: 3 December 2021)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Sheppard, Scott S. (March 2014). "A Sedna-like body with a perihelion of 80 astronomical units" (PDF). Nature. 507 (7493): 471–474. arXiv:2310.20614. Bibcode:2014Natur.507..471T. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ad2686. PMID 24670765. S2CID 4393431. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2014.

- ^ "2012 VP113 – Summary". AstDyS-2, Asteroids – Dynamic Site. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Witze, Alexandra (26 March 2014). "Dwarf planet stretches Solar System's edge". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.14921. S2CID 124305879.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lakdawalla, Emily (26 March 2014). "A second Sedna! What does it mean?". Planetary Society blogs. The Planetary Society.

- ^ a b Proudfoot, Benjamin (August 2025). "A Search For The Moons of Mid-Sized TNOs". Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes. Space Telescope Science Institute: HST Proposal 18010. Bibcode:2025hst..prop18010P. Cycle 33. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ a b c "NASA Supported Research Helps Redefine Solar System's Edge". NASA. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ a b c "2012 VP113". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b Sheppard, Scott S. "Beyond the Edge of the Solar System: The Inner Oort Cloud Population". Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution for Science. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Sample, Ian (26 March 2014). "Dwarf planet discovery hints at a hidden Super Earth in solar system". The Guardian.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (26 March 2014). "A New Planetoid Reported in Far Reaches of Solar System". The New York Times.

- ^ Wall, Mike (26 March 2014). "New Dwarf Planet Found at Solar System's Edge, Hints at Possible Faraway 'Planet X'". Space.com web site. TechMediaNetwork. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "A new object at the edge of our Solar System discovered". Physorg.com. 26 March 2014.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (1 September 2014). "Extreme trans-Neptunian objects and the Kozai mechanism: signalling the presence of trans-Plutonian planets". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 443 (1): L59–L63. arXiv:1406.0715. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443L..59D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slu084.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl; Aarseth, S. J. (11 January 2015). "Flipping minor bodies: what comet 96P/Machholz 1 can tell us about the orbital evolution of extreme trans-Neptunian objects and the production of near-Earth objects on retrograde orbits". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 446 (2): 1867–1873. arXiv:1410.6307. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.446.1867D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2230.

External links

[edit]- 2012 VP113 Inner Oort Cloud Object Discovery Images from Scott S. Sheppard/Carnegie Institution for Science.

- 2012 VP113 has Q=460 ± 30 Archived 28 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (mpml: CFHT 2011-Oct-22 precovery)

- List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects, Johnston's Archive

- List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects, Minor Planet Center

- 2012 VP113 at the JPL Small-Body Database