Wiki Article

Planetary romance

Nguồn dữ liệu từ Wikipedia, hiển thị bởi DefZone.Net

Planetary romance[1] (other synonyms are sword and planet,[2][3][4][5] and planetary adventure[6][7]) is a subgenre of science fiction or science fantasy in which the bulk of the action consists of adventures on one exotic alien — often technologically primitive — world,[8] characterized by distinctive physical and cultural backgrounds.[9] Some planetary romances take place against the background of a future culture where travel between worlds by spaceship is commonplace; others, particularly the earliest examples of the genre, do not, invoking flying carpets, astral projection, or other methods of getting between planets. In either case, it is the planetside adventures that are the focus of the story, not the mode of travel.[9]

Prototypes and characteristics

[edit]

As the label itself implies, the planetary romance extends the late-19th- and early-20th-century adventure-romance and pulp traditions to a planetary setting.[9][10] Popular adventure fiction by writers such as H. Rider Haggard and Talbot Mundy placed bold protagonists in exotic milieus and "lost worlds"—for instance in still-unmapped regions of South America, Africa, or the Middle East and Far East—while a parallel variant was set in imagined or historical locales of antiquity and the Middle Ages, trends that also fed into the modern fantasy genre.[11]

In planetary romance, the narrative energies of space opera are applied to the popular adventure mode (note that in English romance here denotes heroic, mythic, and allegorical narrative rather than the realist novel).[12] The stalwart adventurer becomes a space traveller, often from Earth, which functions analogically as the modern Western world and North America—centres of technology and (self-conscious) colonialism.[9][13] The other worlds—very often, in early examples, Mars and Venus—replace Asia and Africa as the exotic elsewhere, while hostile tribes of aliens and their decadent monarchies take the place of stock Western images of "savage races" and "oriental despotism."[13][14] Although the planetary romance has been used to voice a wide spectrum of political and philosophical positions, a persistent subject is first contact—encounters between alien civilizations, the difficulties of communication, and the frequent disasters that ensue.[15]

The expression "planetary romance" is attested at least as early as 1978, when Russell Letson, in his introduction to the reissue of Philip José Farmer's novel The Green Odyssey (1957), described the tradition explicitly:[8][9]

The major tradition is the subgenre which may be called the "planetary romance". This subgenre is distinguished from its close cousins, the space opera and the sword and sorcery fantasy, by its setting (an exotic, technologically primitive planet), although it shares with them the adventure-plot conventions of chases, escapes, and quests.

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction mentions two caveats as to the usage of the term. First, while the setting may be in an alien world, if "the nature or description of this world has little bearing on the story being told," as in A Case of Conscience, then the book is not a planetary romance. Second, hard science fiction tales are excluded from this category, where an alien planet, while being a critical component of the plot, is just a background for a primarily scientific endeavor, such as Hal Clement's Mission of Gravity,[9] possibly with embellishments. Allen Steele writes that while the label "space opera" has been posted on any story away from Earth, it stands apart from "planetary romance", which he describes as a "close cousin" of "space opera".[1]

Early examples in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

[edit]Among nineteenth-century prototypes of the form—mostly set on Mars—is Across the Zodiac (1880) by Percy Greg, which employs "apergy" (a speculative form of antigravity) to reach the Red Planet.[16] A significant precursor of the genre is Edwin L. Arnold's Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation (1905), in which an officer reaches Mars by magic carpet and undertakes an adventure with a princess, a theme later developed more successfully by Edgar Rice Burroughs.[17] In the same vein are Gustavus W. Pope's "Romances of the Planets": Journey to Mars (1894) and Journey to Venus (1895).[18]

In the early twentieth century, A Voyage to Arcturus (1920) by David Lindsay is often read less as straightforward science fiction than as a philosophical novel, using the alien world principally as a vehicle for exploring philosophical themes.[19]

Edgar Rice Burroughs and "sword and planet" stories

[edit]

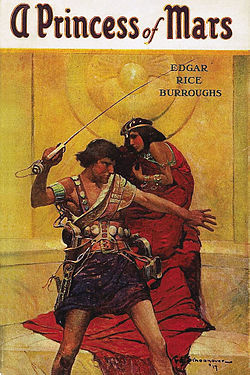

The first writer to reach a wide market for this kind of story was Edgar Rice Burroughs, whose initial Barsoom (Mars) tales appeared in the pulp magazine The All-Story in 1912.[20][9]

Burroughs's Barsoom presents a colorful, heterogeneous mix of cultures and technologies that is typical of classic planetary romance.[9] Among its futuristic devices are the "radium engine" and aircraft sustained by the "eighth ray," which provides buoyancy.[21] The setting features Martian cavalry and a dynastic social order of emperors and princesses.[20]

The content of the Barsoom saga is steeped in swashbuckling adventure: frequent duels, arena combats, hairbreadth escapes, and clashes with monstrous creatures; for these works, the retrospective label "sword and planet" has often been applied.[9][21]

These novels belong as much to science fiction as to fantasy, although elements of "pure" fantasy and the supernatural are minimized or given in-universe explanations: on Barsoom, faculties such as telepathy operate machinery by thought in A Princess of Mars, while cults and supposed deities are unmasked as superstition or imposture within the narrative.[20]

The Dune universe created by Frank Herbert and Star Wars by George Lucas both draw on this fusion of the futuristic with the quasi-medieval—knightly orders, principalities, and codes of honor reframed through technology.[9][22][23]

Thanks to Burroughs's success, numerous imitators followed, including Otis Adelbert Kline, who consciously adopted the adventurous planetary romance pattern in his Venus trilogy (the Grandon of Venus books) and later his Mars duology (the Swordsman of Mars novels).[24] Burroughs himself revisited the formula with the Venus series (Carson of Venus) in the 1930s.[20] In 2007 the American publisher Paizo launched the Planet Stories imprint to reissue classics of science fantasy and planetary romance, including new editions of Kline's Martian novels.[25][24]

The pulps and the codification of the form (1926–1939)

[edit]

The rise of specialized science fiction pulps from 1926—beginning with the launch of Amazing Stories in April—opened a new market for adventure tales set on other worlds, a market that expanded markedly through the 1930s.[26][10]

Among the new periodicals, Planet Stories (from 1939) stood out, being designed to publish exclusively adventure-centered interplanetary fiction.[27] In the same year Startling Stories (Standard/Better Publications) also debuted as a sister title to Thrilling Wonder Stories, with a one-complete-novel-per-issue format.[28][29] In parallel, established fantastic-fiction magazines such as Weird Tales had, from the outset, alternated weird-science and scientific detection with the more familiar fantasy and horror.[30]

One of the leading writers in the mode was C. L. Moore, with the cycle about the adventurer Northwest Smith, inaugurated by the story Shambleau in Weird Tales (November 1933).[31] In Moore's stories the swashbuckling action recedes before psychological tension and the push-and-pull of fear and fascination for the unknown, often with an explicitly erotic component.[32][33][34]

Robert E. Howard engaged the form with Almuric (1939), a three-part novel with strongly adventure-forward plotting set on an alien planet dominated by tribal societies and a hostile environment, where physical conflict and survival take center stage. The book translates into a planetary frame the narrative models of heroic and pulp fiction, with a terrestrial protagonist asserting physical superiority in an exotic, primitive world.[35]

Stanley G. Weinbaum contributed A Martian Odyssey (1934), often cited as an early planetary romance that advances a more articulated imagining of alien otherness: Mars is not merely an exotic backdrop but the site of encounter with a radically different being, described with biological and cultural attentiveness—anticipating concerns central to the more mature genre.[36][37]

1940s and 1950s: consolidation and maturation

[edit]

In the 1940s and 1950s, one of the most significant contributions to the mode came from Leigh Brackett, a regular in Planet Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories, who honed a controlled, adventure-forward strain of planetary romances often set on a Mars cognate with Burroughs's.[38][39][40][41] Within this period fall the three short novels in the Eric John Stark sequence that ran in Planet Stories: The Secret of Sinharat (originally Queen of the Martian Catacombs, Summer 1949), People of the Talisman (originally Black Amazon of Mars, March 1951), and Enchantress of Venus (Autumn 1949).[41]

In parallel, Startling Stories published key texts: in August 1952 Philip José Farmer's The Lovers and in September 1952 Jack Vance's Big Planet.[29] The Lovers, later expanded to book length in 1961, made Farmer famous for its joint treatment of sexual and xenobiological themes and won him the 1953 Hugo as "most promising new writer."[42] Big Planet provided a long-running science-fictional model for the planetary romance: an immense world poor in metals, which fosters low-technology societies. Much of Vance's later SF belongs to the mode: the sequel Showboat World (1975); the Alastor cluster trilogy; the Durdane trilogy; the Cadwal Chronicles; the four-volume Planet of Adventure (also known as the Tschai sequence, 1968–1970); many of the Magnus Ridolph stories; the five-volume Demon Princes; and stand-alone works such as Maske: Thaery (1976) and the story The Moon Moth (1961).[43]

Among writers active from the 1930s through the 1950s was Murray Leinster: his The Forgotten Planet (1954) assembled, as a fix-up novel, material originally published between 1920 and 1953.[44] In the same time frame, C. S. Lewis issued his Space Trilogy: Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1943), and That Hideous Strength (1945).[45]

The Survivors (1958) by Tom Godwin is an epic about four thousand human colonists abandoned to die on a cold, hostile world. The Forgotten Planet (1954) by Murray Leinster—whose first two chapters were published as stories in 1920 and 1921—relates the fortunes of a small group of humans regressed on a world only partially terraformed.[46][44]

From the 1960s onward

[edit]

From the mid-1960s onward, the traditional Solar-System planetary romance waned in popularity as space exploration revealed the hostility and desolation of nearby planets—most notably with the 1965 Mariner 4 images that dramatically altered the popular and genre perception of Mars.[47] In parallel, writers increasingly shifted their stories to exoplanetary settings, breezily invoking conventions such as hyperspace or other faster-than-light devices to justify interstellar travel.[13][48]

An exception is the long-running Gorean sequence by John Norman, launched with Tarnsman of Gor (1966): the cycle is set on a Counter-Earth that shares Earth's orbit, located on the opposite side of the Sun near the system's L3 point.[49][50] The astronomically problematic premise is presented without real physical justification, a convention long tolerated within the subgenre.[49]

At the same time, a self-conscious retro revival of sword and planet emerged. Lin Carter inaugurated the Callisto cycle with Jandar of Callisto (1972), an explicit homage to Edgar Rice Burroughs and his Martian scenarios.[51] Michael Moorcock, under the pseudonym Edward P. Bradbury, offered his own Martian trilogy featuring Kane of Old Mars (1965).[52] In the same years Kenneth Bulmer, chiefly as Alan Burt Akers, launched the expansive Dray Prescot cycle set on Kregen, explicitly conceived as a Burroughsian pastiche, published for decades by DAW Books and later continued with installments that first appeared in German translation.[53]

Within the rationalized tradition sits the Krishna sequence by L. Sprague de Camp, embedded in the wider Viagens Interplanetarias setting (from 1949 into the early 1990s): the novels play out on exoplanets inhabited by technologically backward civilizations, described with systematic attention to social structures, customs, and institutions, and framed as quasi-anthropological objects of study by the Terran protagonists.[54][55]

A number of large-scale SF cycles are frequently cited as representative planetary romances. Notable among these are the Darkover series (from 1958) by Marion Zimmer Bradley,[9][56] and the Dragonriders of Pern sequence (from 1967) by Anne McCaffrey.[57][58] In Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels (1985), editor and critic David Pringle named Marion Zimmer Bradley and Anne McCaffrey as two "leading practitioners nowadays" of planetary romance.[59]

The Dune cycle by Frank Herbert (from 1963)—especially the early novels predominantly set on Arrakis—integrates hallmark planetary-romance elements into a broader SF architecture of political, religious, and ecological themes;[60][22] Herbert initially considered setting his epic on Mars before opting for an invented planet.[61] Dune has been called by some critics the best SF novel ever written[62] and is probably the best-selling worldwide.[63] It was included in the BBC's 2019 list of 100 novels that shaped our world,[64] and credited with helping pivot the genre toward politically, religiously, and ecologically complex worlds.[65]

Early works in Ursula K. Le Guin's Hainish universe are set on alien planets: Rocannon's World and Planet of Exile (both 1966).[66][67]

Also within the frame belong Pierre Boulle's Planet of the Apes (1963), a satirical and philosophical novel that reverses human/ape relations for social critique and reflection on civilization and its founding myths.[68][69] In the same constellation are Harry Harrison's Planet of the Damned (1962) and Planet of No Return (1981), which cast single-world adventure through scenarios of colonization and social conflict, with elements of sociological critique of colonial contexts and power mechanisms.[70][71]

Developments in the 1970s–1980s include Larry Niven's Ringworld (1970), where the setting is a planet-sized megastructure that reorients surface exploration to an enormously expanded scale while preserving the logic of a single "world" with distinct regions, cultures, and hazards.[72][73] Robert Silverberg's Majipoor Chronicles (1982) gathers linked tales on a richly imagined world, continuing the sequence begun with Lord Valentine's Castle (1980).[74] Brian Aldiss's Helliconia trilogy (1982–1985) centers on a planet subject to exceptionally long seasonal cycles (the "Great Year"), shaping society and history according to astronomical and climatic dynamics.[75][76]

In the early 1990s, French author Ayerdhal published the large-scale trilogy Mytale (1991), insisting on dense, exotic worldbuilding and a pseudo-ethnological framework.[77][78] In the same decade, Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars trilogy (1992–1996) returned the focus to long-term adventure on a single planet, following the colonization and terraforming of Mars and entangling the "surface" progression with a debate of ideas about ecology, politics, and social models.[79][80][47] Catherine Asaro's Skolian Empire saga (from 1995) reworks exotic-world adventure in dynastic, romance-adjacent terms: for example, Catch the Lightning (1996) situates a substantial portion on an alternate Earth before opening onto the interstellar frame, while The Last Hawk (1997) centers on the protagonist's crash-landing on a matriarchal planet and its social and political consequences.[81]

By now, planetary romance has become a significant component of contemporary SF,[9] though few authors use the label for their own work. Given the mutual hybridization of planetary romance and space opera, many stories are difficult to classify exclusively as one or the other.[9][82]

Comics

[edit]

In comics, interplanetary adventure in a popular key finds a decisive reference point in Flash Gordon by Alex Raymond, debuting as a newspaper strip in 1934; critics rank it among the foundations of science fiction comics and relate it to the romances of Edgar Rice Burroughs, helping to establish a durable imaginary of adventure on exotic worlds.[83][84]

In the United States, Planet Comics (1940–1953)—the comic-book "companion" to the pulp magazine Planet Stories—specialized in interplanetary adventure and is described as consisting largely of "planetary romances" set within the Solar System.[85][84]

In Italy, an early case is S.K.1 by Guido Moroni Celsi, a strip for Topolino launched in 1935; it has been considered a space opera largely inspired by, and in large measure copied from, Flash Gordon, and is classed by many scholars—though within the SF context—as "fantasy."[86]

During the postwar years and the Silver Age, the formula of adventure on other worlds was updated by Adam Strange (1958, DC Comics), often described as an obvious imitation of John Carter of Mars: a terrestrial archaeologist teleported to the planet Rann in the Alpha Centauri system.[87][88]

A planetary epic reimagined in family terms is Space Family Robinson, published by Gold Key Comics from 1963, which bears many similarities to the later TV series Lost in Space (1965–1968); both were loosely inspired by The Swiss Family Robinson (1812) by Johann David Wyss, a canonical robinsonade.[89][90]

In the 1970s the tradition hybridized with fantasy in long-running independent series such as Elfquest (from 1978) by Wendy and Richard Pini, set on the "World of Two Moons," a planet with an autochthonous human population but also home to elves and trolls descended from alien ancestors; this science-fictional premise underpins a narrative constructed in the key of high fantasy.[91]

Filmography

[edit]

A concise list of films and TV series that centre on adventure and survival on a single alien world.

- Aelita (1924), by Yakov Protazanov. Among the earliest feature-length works set on Mars, with palace intrigue and adventure on the Red Planet; it also influenced the look of Flash Gordon in its planetary costumes and sets.[92]

- Flash Gordon (1936), a film serial from the Flash Gordon newspaper strip by Alex Raymond. It brings to the screen the archetype of planetary adventure with journeys to Mongo, rival realms, and duels that became a durable audiovisual model for the theme.[83]

- Planet of Storms (1962), adapted from a novel by Alexander Kazantsev and directed by Pavel Klushantsev. A Soviet film about a cosmonaut expedition to Venus, exemplifying the mode with surface exploration, environmental hazards, and hostile fauna on an alien world.[93]

- Barbarella (1968), directed by Roger Vadim. Adapted from Jean-Claude Forest's comic, it translates interplanetary adventure into a pop register of alien cities and powers, consolidating a widely imitated "planetary" imaginary.[94]

- Fantastic Planet (1973), directed by René Laloux. An animated example entirely set on the alien world Ygam, focused on interspecies relations and on building an ecosystem and autochthonous cultures.[95]

- Flash Gordon (1980), directed by Mike Hodges. A pop, camp reprise of interplanetary adventure with exotic worlds, alien monarchies, and knightly trials on Mongo.[83]

- Dune (1984), directed by David Lynch. Adapts the epic set on Arrakis, where the centrality of the desert planet, its resources, and its cultures embodies a key instance of cinematic planetary romance.[96]

- Gor (1987), directed by Fritz Kiersch. Loosely based on John Norman's Tarnsman of Gor, set on a Counter-Earth of city-states, castes, and warrior codes; it directly reprises planetary-romance and sword-and-planet motifs. The sequel is Outlaw of Gor (1988).[49]

- Earth 2 (1994–1995), television series. The saga of a small group of colonists on planet G-889, casting classic themes—colonization, survival, and interaction with an alien environment—in an adventure frame.[97]

- Pitch Black (2000), directed by David Twohy. A survival film on an alien planet where shipwrecked travellers are besieged by photophobic creatures; though commonly classed as SF with strong horror elements, its surface-action and world-bound hazards align it with planetary romance.[98][99]

- Frank Herbert's Dune (2000), a television miniseries that adapts Herbert's first novel, foregrounding Arrakis and the interplay of planetary ecology, political power, and armed conflict.[100]

- Frank Herbert's Children of Dune (2003), a television miniseries. A direct sequel adapting Dune Messiah and Children of Dune, amplifying the epic arc and historical dimension of Arrakis.[100]

- Flash Gordon (2007–2008), television series inspired by the comic strip. A contemporary reworking of planetary adventure with passages between Earth and Mongo and conflicts among local houses and powers.[83]

- Avatar (2009), directed by James Cameron. Often described as a rare cinematic incursion into planetary romance: elaborate worldbuilding and a colonial conflict rooted in the specific ecology and cultures of Pandora.[101][102]

- John Carter (2012), directed by Andrew Stanton. A direct transposition of the Burroughsian template, set on Barsoom with city-states, duels, and alien cultures typical of the mode.[103]

- Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (2017), directed by Luc Besson. Adapted from the French comic Valérian et Laureline, it parades a baroque, adventure-forward imaginary in a universe of many species and cultures, pertinent by continuity with "planetary" exoticism reframed as a travelling macrostructure.[104]

- Annihilation (2018), directed by Alex Garland. From Jeff VanderMeer's novel; it follows an expedition into "the Shimmer," an anomaly enclosing seemingly alien ecosystems, a boundary case for the mode that emphasizes geography and aberrant biology as drivers of action.[105]

- Dune: Part One (2021), directed by Denis Villeneuve. Adapts the first half of Herbert's novel, strongly centring the setting of Arrakis with high fidelity in plot and worldbuilding; planetary construction and the ecology of the spice orient action and adventure.[106][107]

- After Blue (Paradis sale) (2021), directed by Bertrand Mandico. An odyssey across an entirely "other" colony world (a planet inhabited only by women), structured as an episodic journey of encounters.[108]

- Avatar: The Way of Water (2022), directed by James Cameron. Continues the adventure on Pandora and maintains the centrality of an alien world as the theatre of action.[109][101]

- Scavengers Reign (2023), animated series created by Joseph Bennett and Charles Huettner. An adult-aimed series set almost entirely on the planet Vesta, where ecology and life-cycles drive the narrative.[110]

- Dune: Part Two (2024), directed by Denis Villeneuve. Completes the adaptation of Herbert's original novel, heightening the war-adventure dimension and deepening political and cultural conflicts on Arrakis.[111][22]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Steele, Allen. Captain Future – The Horror at Jupiter. p. 195.

- ^ Dozois & Martin 2015, p. xiii.

- ^ Caryad, Römer & Zingsem 2014, p. 78.

- ^ Duncan 2010, p. 204.

- ^ Jones & Rhodes 2008, p. 978.

- ^ Asaro, Catherine; Dolan, Kate (2012). "The Literature of Planetary Adventure". In Brooke, Keith (ed.). Strange Divisions and Alien Territories: The Sub-Genres of Science Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 39–60.

- ^ Before the New Wave (Part I). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-16609-7. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

Planet Stories, launched at the end of 1939, focused primarily on planetary adventure.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b Letson, Russell (1978). "Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: planetary romance". Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Planetary Romance". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b "SF Magazines". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Lost Worlds". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Wolfe 1986.

- ^ a b c "Mars". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Venus". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "First Contact". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Greg, Percy". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Arnold, Edwin L". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Pope, Gustavus W". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Lindsay, David". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b c d "Burroughs, Edgar Rice". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b ""A Princess of Mars" – item record". Library of Congress, Read.gov. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b c "Herbert, Frank". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Star Wars". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b "Kline, Otis Adelbert". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Planet Stories". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Ashley 2000, p. 238.

- ^ Ashley 2000, p. 152.

- ^ Ashley 2000, p. 250.

- ^ a b "Startling Stories". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Ashley 2000, pp. 139–140.

- ^ "Weird Tales, vol. 22, no. 5 (Nov. 1933): "Shambleau," pp. 531–550" (PDF). Internet Archive. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Bredehoft 1997, pp. 369–386.

- ^ "Moore, C L". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Brett, J. (2009). "The Vampire Story in Weird Tales from 1920–1939". Texas A&M University OAKTrust. p. 6. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Howard, Robert E." The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "A Martian Odyssey". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Weinbaum, Stanley G." The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Wolfe 1986, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Davin 2006, pp. 213–221.

- ^ James 2003, p. 44.

- ^ a b "Brackett, Leigh". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Farmer, Philip José". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Vance, Jack". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b "Leinster, Murray". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Lewis, C S". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Godwin, Tom". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b Markley 2005, pp. 230–236.

- ^ "Hyperspace". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b c "Norman, John". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Counter-Earth". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Carter, Lin". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Moorcock, Michael". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Bulmer, Kenneth". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "de Camp, L Sprague". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Wolfe 1986, pp. 86–88.

- ^ "Darkover Series". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Pern [series]". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "McCaffrey, Anne". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Pringle 1985, p. 17.

- ^ "Dune". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (October 21, 2021). "How the Dune science-fiction saga parallels the real science of Oregon's dunes". GeekWire. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Johansson 2004, p. 78.

- ^ "Frank Herbert". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Discworld dishes Moby-Dick: BBC unveils 100 novels that shaped our world". The Guardian. November 5, 2019. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Kennedy 2022, pp. 1–17.

- ^ "Le Guin, Ursula K". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Rocannon's World — editions and translations". ISFDB. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Boulle, Pierre". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Devolution". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Harrison, Harry". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Colonization of Other Worlds". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Niven, Larry". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Macrostructures". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Silverberg, Robert". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Aldiss, Brian W". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Great Year". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Ayerdhal — bibliography". ISFDB. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Sice, David. "Mytale". Le Bélial'. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Robinson, Kim Stanley". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Costanza, Robert (2000). "Future Visions of Earth from Mars" (PDF). robertcostanza.com. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Asaro, Catherine". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Space Opera". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b c d "Flash Gordon". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b "Comics". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Planet Comics". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Eventi e notizie storiche 2002–2013 (S.K.1), pp. 38–39" (PDF). Fondazione Cesare Zavattini. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Adam Strange". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Adam Strange". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Gold Key Comics". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Lost in Space". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ Guillaume, Isabelle L. (19 December 2016). "Women W.a.R.P.ing Gender in Comics: Wendy Pini's Elfquest as mixed power fantasy". Revue de Recherche en Civilisation Américaine (6). Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Aelita". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Planeta Bur". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Barbarella". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "La Planète Sauvage". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Dune (1984)". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Earth 2". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Pitch Black". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Horror in SF". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b "Television". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ a b "Avatar". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Cameron, James". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "John Carter". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Annihilation". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Dune: Part One". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Dune (2021) review". BFI Sight & Sound. 25 October 2021. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "After Blue". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Avatar: The Way of Water review". BFI Sight & Sound. 16 November 2022. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Scavengers' Reign". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

- ^ "Dune: Part Two review". BFI Sight & Sound. Retrieved 2026-01-05.

Works cited

[edit]- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines: The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the Beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9780853238652.

- Bredehoft, Thomas A. (1997). "Origin Stories: Feminist Science Fiction and C. L. Moore's "Shambleau"". Science Fiction Studies. 24 (3): 369–386. doi:10.1525/sfs.24.3.0369.

- Clute, John (1995). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 9780312134860.

- Crossley, Robert (2011). Imagining Mars: A Literary History. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 9780819569271.

- Davin, Eric Leif (2006). Partners in Wonder: Women and the Birth of Science Fiction, 1926–1965. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739112670.

- James, Edward (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521016575.

- Dozois, Gardner; Martin, George R. R., eds. (2015). Old Venus. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 9780804179850.

- Caryad; Römer, Thomas; Zingsem, Vera (2014). Wanderer am Himmel: Die Welt der Planeten in Astronomie und Mythologie. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9783642553431.

- Duncan, Randy (2010). Booker, M. Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9780313357473.

- Jones, Howard Andrew; Rhodes, Robert (2008). Womack, Kenneth (ed.). Books and Beyond: The Greenwood Encyclopedia of New American Reading. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9780313071577.

- Johansson, Frans (2004). The Medici Effect: Breakthrough Insights at the Intersection of Ideas, Concepts, and Cultures. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 9781591391869.

- Kennedy, Kara (2022). "Introduction". Women's Agency in the Dune Universe: Tracing Women's Liberation through Science Fiction. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–17. ISBN 9783031139352.

- Markley, Robert (2005). "The Missions to Mars: Mariner, Viking, and the Reinvention of a World". Dying Planet: Mars in Science and the Imagination. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 230–236. ISBN 9780822336389.

- Pringle, David (1985). Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels. An English-Language Selection, 1949–1984. London: Xanadu Publications. ISBN 9780947761110.

- Seed, David (2011). Science Fiction: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199557455.

- Westfahl, Gary, ed. (2005). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313329500.

- Wolfe, Gary K. (1986). Critical Terms for Science Fiction and Fantasy: A Glossary and Guide to Scholarship. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313229817.