Kiết sử

Bài này không có nguồn tham khảo nào. |

Bài viết hoặc đoạn này cần người am hiểu về chủ đề này trợ giúp biên tập mở rộng hoặc cải thiện. |

| Một phần của loại bài về |

| Phật giáo |

|---|

|

|

|

Trong Phật giáo, kết (tiếng Phạn: saṃyojana, tiếng Pali: saṃyojana, saññojana, Hán tự: 結), còn gọi là kiết sử, là những phiền não trong nội tâm ý thức của con người, sinh ra những chướng ngại khiến cho con người sa vào vòng luân hồi không thể giải thoát. Theo quan điểm Phật giáo, cần phải tiêu trừ những kiết sử này, con người mới có thể nhập Niết-bàn.

Giữa các kinh điển Phật giáo có những khác biệt về phân loại và số lược các kiết sử, theo đó có thể phân ra thành nhị kết, tam kết, tứ kết, ngũ kết, cửu kết và thập kết.

Danh sách kiết sử

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- Thân kiến (sakkàya-ditthi)[1]

- Hoài nghi (vicikicchà)[2]

- Giới cấm thủ (silabata-paràmàsa)[3]

- Tham đắm vào cõi dục (kàma-ràga)[4]

- Sân hận (vyàpàda)[5]

- Tham đắm vào cõi sắc (rùpa-ràga)[6]

- Tham đắm vào cõi vô sắc (arùpa-ràga)[7]

- Mạn (màna)[8][9]

- Trạo cử vi tế (uddhacca)[10]

- Vô minh (avijjà)[11]

Chú thích

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- ^ Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), pp. 660-1, "Sakkāya" entry (retrieved 2008-04-09), defines sakkāya-diṭṭhi as "theory of soul, heresy of individuality, speculation as to the eternity or otherwise of one's own individuality." Bodhi (2000), p. 1565, SN 45.179, translates it as "identity view"; Gethin (1998), p. 73, uses "the view of individuality"; Harvey (2007), p. 71, uses "views on the existing group"; Thanissaro (2000) uses "self-identify views"; and, Walshe (1995), p. 26, uses "personality-belief."

- ^ Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), p. 615, "Vicikicchā" entry (retrieved 2008-04-09), defines vicikicchā as "doubt, perplexity, uncertainty." Bodhi (2000), p. 1565, SN 45.179, Gethin (1998), p. 73, and Walshe (1995), p. 26, translate it as "doubt." Thanissaro (2000) uses "uncertainty." Harvey provides, "vacillation in commitment to the three refuges and the worth of morality" (cf. M i.380 and S ii.69-70).

- ^ See, for instance, Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), p. 713, "Sīla" entry (retrieved 2008-04-09), regarding the similar concept of sīlabbatupādāna (= sīlabbata-upādāna), "grasping after works and rites." Bodhi (2000), p. 1565, SN 45.179, translates this term as "the distorted grasp of rules and vows"; Gethin (1998), p. 73, uses "clinging to precepts and vows"; Harvey (2007), p. 71, uses "grasping at precepts and vows"; Thanissaro (2000) uses "grasping at precepts & practices"; and, Walshe (1995), p. 26, uses "attachment to rites and rituals."

- ^ For a broad discussion of this term, see, e.g., Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), pp. 203-4, "Kāma" entry, and p. 274, "Chanda" entry (retrieved 2008-04-09). Bodhi (2000), p. 1565 (SN 45.179), Gethin (1998), p. 73, Harvey (2007), p. 71, Thanissaro (2000) and Walshe (1995), p. 26, translate kāmacchando as "sensual desire."

- ^ Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), p. 654, "Vyāpāda" entry (retrieved 2008-04-09), defines vyāpādo as "making bad, doing harm: desire to injure, malevolence, ill-will." Bodhi (2000), p. 1565, SN 45.179, Harvey (2007), p. 71, Thanissaro (2000) and Walshe (1995), p. 26, translate it as "ill will." Gethin (1998), p. 73, uses "aversion."

- ^ Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), pp. 574-5, "Rūpa" entry (retrieved 2008-04-09), defines rūparāgo as "lust after rebirth in rūpa." Bodhi (2000), p. 1565, SN 45.180, translates it as "lust for form." Gethin (1998), p. 73, uses "desire for form." Thanissaro (2000) uses "passion for form." Walshe (1995), p. 27, uses "craving for existence in the Form World."

- ^ Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), pp. 574-5, "Rūpa" entry (retrieved 2008-04-09), suggests that arūparāgo may be defined as "lust after rebirth in arūpa." Bodhi (2000), p. 1565, SN 45.180, translates it as "lust for the formless." Gethin (1998), p. 73, uses "desire for the formless." Harvey (2007), p. 72, uses "attachment to the pure form or formless worlds." Thanissaro (2000) uses "passion for what is formless." Walshe (1995), p. 27, uses "craving for existence in the Formless World."

- ^ Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), p. 528, "Māna" entry (retrieved 2008-04-09), defines māna as "pride, conceit, arrogance." Bodhi (2000), p. 1565, SN 45.180, Thanissaro (2000) and Walshe (1995), p. 27, translate it as "conceit." Gethin (1998), p. 73, uses "pride." Harvey (2007), p. 72, uses "the 'I am' conceit."

- ^ For a distinction between the first fetter, "personal identity view," and this eighth fetter, "conceit," see, e.g., SN 22.89 (trans., Thanissaro, 2001).

- ^ Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), p. 136, "Uddhacca" entry (retrieved 2008-04-09), defines uddhacca as "over-balancing, agitation, excitement, distraction, flurry." Bodhi (2000), p. 1565 (SN 45.180), Harvey (2007), p. 72, Thanissaro (2000) and Walshe (1995), p. 27, translate it as "restlessness." Gethin (1998), p. 73, uses "agitation."

- ^ Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), p. 85, "Avijjā" entry (retrieved 2008-04-09), define avijjā as "ignorance; the main root of evil and of continual rebirth." Bodhi (2000), p. 1565 (SN 45.180), Gethin (1998), p. 73, Thanissaro (2000) and Walshe (1995), p. 27, translate it as "ignorance." Harvey (2007), p. 72, uses "spiritual ignorance."

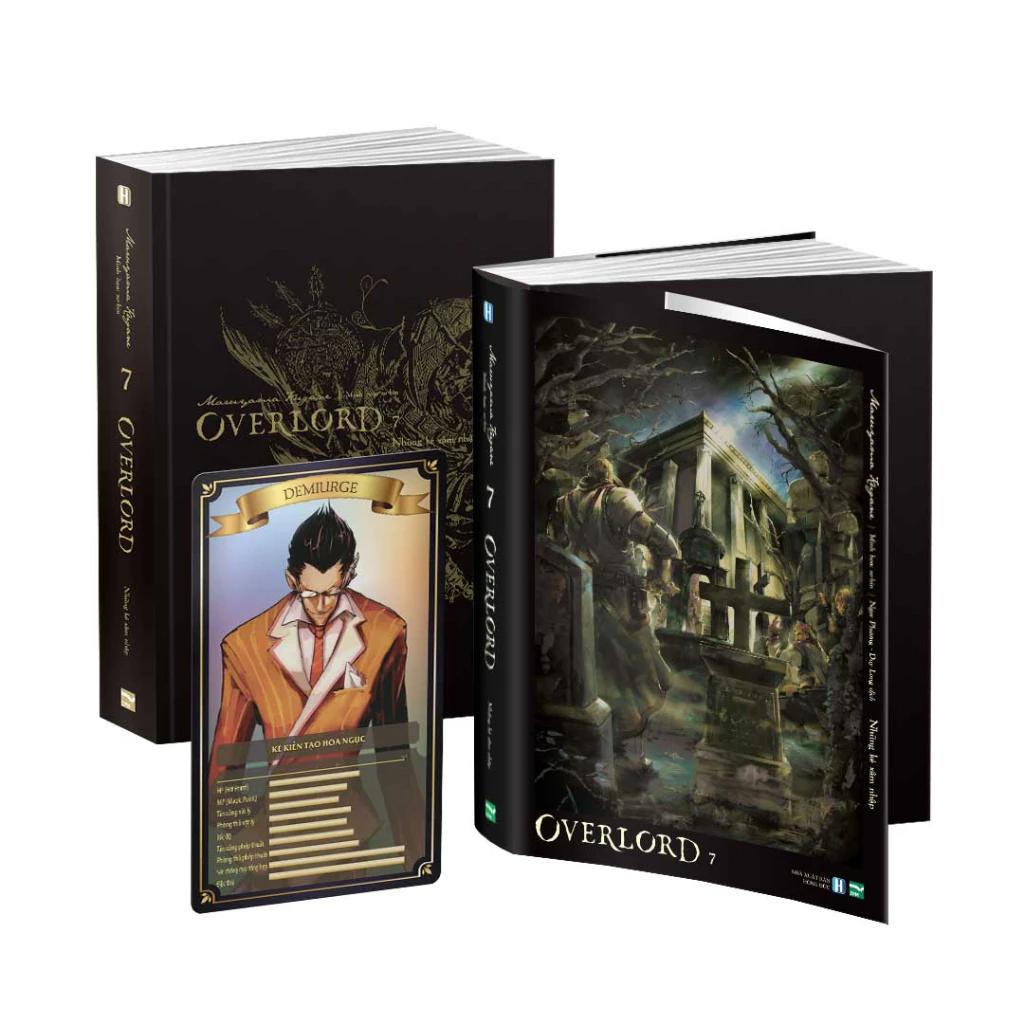

Chúng tôi bán

GIẢM

20%

GIẢM

20%

140.000 ₫

175.000 ₫

GIẢM

21%

GIẢM

21%

190.000 ₫

240.000 ₫

GIẢM

38%

GIẢM

38%

75.000 ₫

120.000 ₫

GIẢM

50%

GIẢM

50%

99.000 ₫

198.000 ₫

GIẢM

25%

GIẢM

25%

1.500 ₫

2.000 ₫